Algerian Chronicles, Albert Camus

Translator’s Note

New Perspectives on Camus’s Algerian Chronicles

Algerian Chronicles

Preface

The Misery of Kabylia

1 Destitution

2 Destitution (continued)

3 Wages

4 Education

5 The Political Future

6 The Economic and Social Future

7 Conclusion

Crisis in Algeria

8 Crisis in Algeria

9 Famine in Algeria

10 Ships and Justice

11 The Political Malaise

12 The Party of the Manifesto

13 Conclusion

14 Letter to an Algerian Militant

Algeria Torn

15 The Missing

16 The Roundtable

17 A Clear Conscience

18 The True Surrender

19 The Adversary’s Reasons

20 November 1

21 A Truce for Civilians

22 The Party of Truce

23 Call for a Civilian Truce in Algeria

The Maisonseul Affair

24 Letter to Le Monde

25 Govern!

Algeria 1958

26 Algeria 1958

27 The New Algeria

Appendix

Indigenous Culture: The New Mediterranean Culture

Men Stricken from the Rolls of Humanity

Letter from Camus to Le Monde

Draft of a Letter to Encounter

Two Letters to René Coty

The Nobel Prize Press Conference Incident

Index

Translator’s Note

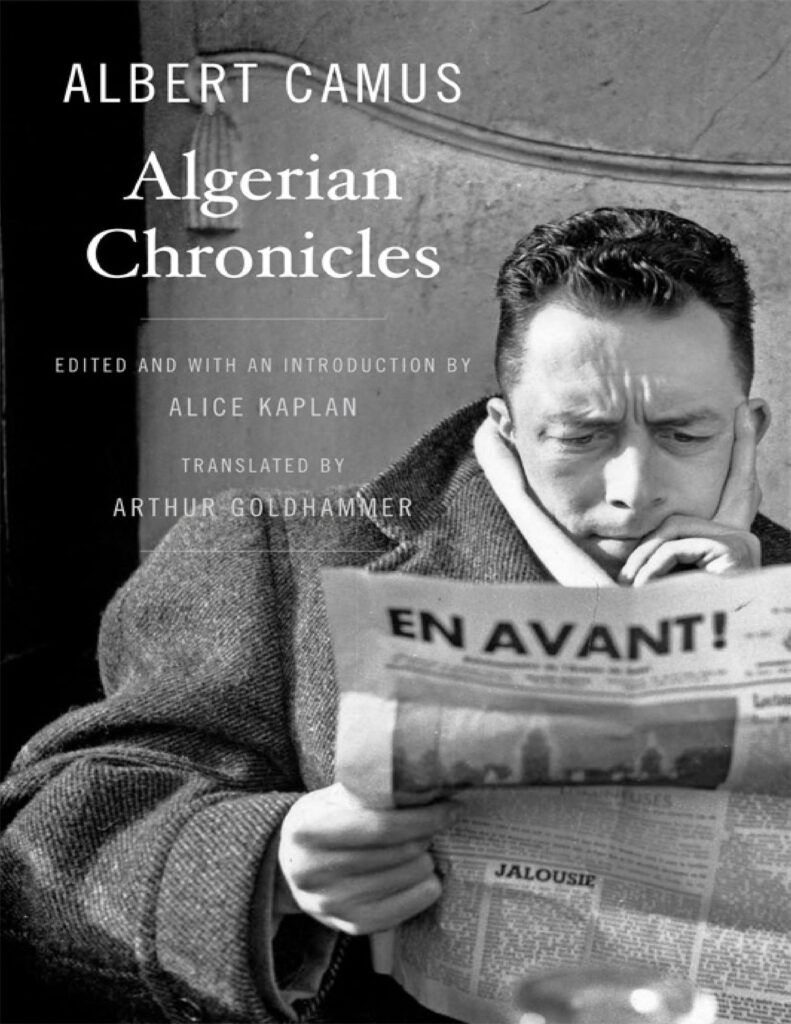

Algerian Chronicles is a moving record of Albert Camus’s distress at his inability to alleviate the series of tragedies that befell his homeland, Algeria, over a period of 20 years, from 1939 to 1958. Camus collected these reactions to current events in a volume originally entitled Actuelles III. It would no doubt have saddened him to learn that the sources of his heartache—the difficulty of reconciling European and non-European cultures, the senseless recourse to violence, the fatal spiral of repression and terror—are once again matters “of actuality,” lending prescience to his original title.

After listening to Camus lecture, the writer Julien Green described him in terms that one might apply to a secular saint: “There is in this man a probity so obvious that it inspires almost immediate respect in me. To put it plainly, he is not like the others.” This quality of authenticity is unmistakable throughout the pieces collected here. Camus wrote as a moralist, in the noblest sense of the term. In fact, he was a moralist in two different senses. In the French sense, he was a worthy heir to La Rochefoucauld and La Bruyère, moralistes who exposed the hidden selfishness in ostensibly selfless action, the hypocrisy in what society, for reasons of its own, hypocritically honors as virtue.

But he was also a moralist in the American sense, a writer of “jeremiads,” which, as Sacvan Bercovitch revealed, are best understood as appeals to the fatherland to return to the high ideals that it has set for itself and from which it has strayed. Here, it is primarily this second type of moralism that is on display. Camus addresses France, his second home, which he believed had not, in its policies toward Algeria, remained true to the founding ideals of its republican tradition—liberty, equality, and fraternity—which for Camus were the political virtues par excellence.

In this respect, Camus was quintessentially French, but he saw himself not only as a Frenchman but also as a man of the Mediterranean, a spiritual heir of Saint Francis who, as Camus put it in an early manifesto on “Mediterranean culture” (included in the supplementary material to this volume), “turned Christianity from a religion of inner torment into a hymn to nature and naïve joy.” But “nature and naïve joy” could not survive in the climate of “soulless violence” that descended on Algeria, the land of Camus’s birth and the very root of his being. The pieces in this volume trace the increasing effect of this violence, not only on Camus’s allegiances but on the language in which he expressed his and his homeland’s suffering.

Abstraction was not Camus’s natural element. In his early reportage, he indulges in a minimum of economic theorizing to set the stage for his narratives, but the force of his writing lies in his ability to make the reader feel what it is like to eat thistle, to depend on capricious handouts, or to die of exhaustion in the snow on the way home from a food distribution center. Although he may on occasion use an abstract and value-laden term like “justice,” what moves him is plain fellow-feeling for other suffering human beings. With almost Franciscan faith he hopes that the example of his own compassion will suffice to elicit the compassion of others.

Attentive to Camus’s text, the translator senses not only his despair of the situation in Algeria but also his exasperation. The political dilemmas of the time were cruel, and no intellectuel engagé escaped from them unscathed. History chose a course different from the one Camus envisioned, but history’s choice has not been so incontrovertibly satisfactory as to rob Camus’s counterfactual alternative of its retrospective grandeur. What we have here is a precious document of a soul’s torment lived in real rather than eternal time. I can only hope that my translation has done it justice.

And it is not easy to do justice to Camus’s style in English. He is a writer who has fully mastered all the resources of concision, subtlety, and grace that French provides. He can maintain perfect equipoise through a series of long sentences and then punctuate his point with a short phrase intensified by a slightly unusual syntax or surprising word choice. To mimic the French structure slavishly is to betray the spirit of the text, which has to be rethought with the different stylistic resources of English in mind. When I think of Camus’s prose, I think of adjectives such as “pure,” “restrained,” and “disciplined.” He never strains for effect, never descends into bathos, and always modulates his passion with classical precision.

When this book originally went to press, Camus was feeling desperate about Algeria’s future, yet he concluded that it was still worth publishing the record of his own engagement, because of the facts it contained. “The facts have not changed,” he wrote, “and someday these will have to be recognized if we are to achieve the only acceptable future: a future in which France, wholeheartedly embracing its tradition of liberty, does justice to all the communities of Algeria without discrimination in favor of one or another. Today as in the past, my only ambition in publishing this independent account is to contribute as best I can to defining that future.” For us, half a century later, the facts still have not changed, and the future to which Camus hoped to contribute has expanded to include not just France but the entire world. Like Camus, we cannot change the obdurate facts of the past, but we can hope to learn from his unflinchingly honest account how better to deal with them in charting our own course.

—Arthur Goldhammer

New Perspectives on Camus’s Algerian Chronicles

ALICE KAPLAN*

*I am grateful to P. Guillaume Michel at the Glycines: Centre d’Etudes Diocésain for his generous introduction to intellectual life in Algiers in the summer of 2012, and to the Algerian scholars who responded to my lecture on the Chroniques algériennes and opened my eyes to new readings of Camus in Algeria today. Comments by David Carroll, James Le Sueur, and Raymond Gay-Crosier on an earlier version of this preface were invaluable.

Albert Camus published his Algerian Chronicles on June 16, 1958, just as France was reeling from her greatest political upheaval since the end of the Second World War. The Fourth Republic had fallen, and when a coup d’état by rebellious French generals in Algeria seemed to be in the offing, General de Gaulle was called back to power to save the Republic. In the throes of a national crisis brought on wholly by the Algerian War, Camus gathered his writing on Algeria from 1939, when he was a political activist and an all-purpose reporter for Alger républicain, through the 1950s. He added an introduction and a concluding essay called “Algeria 1958.” Yet his book was met, paradoxically, with widespread critical silence. The press file in the archives at Gallimard is practically empty—it seemed, on the Algerian question at least, that the French were no longer listening to Camus.

One exception was René Maran, the seventy-one-year-old black French writer from Guadeloupe who had won the Goncourt Prize in 1921 for Batuala, a colonial novel set in Africa. Maran believed that Camus’s essays might one day seem as prescient of Algerian reality as Tocqueville’s had been of life in Russia and the United States.1 Reading the Algerian Chronicles for the first time in Arthur Goldhammer’s elegant, concise translation, we might ask whether Maran was right.

The Algerian Chronicles have a double-edged message, as does so much of Camus’s political writing. Throughout these essays spanning two decades of activism, he remains sensitive to the demands of the Algerian nationalists and their critique of colonial injustice. But an Algeria without the French is unimaginable to him, and he warns that a break with France will be fatal to any conceivable Algerian future.

Camus’s position was appalling to many supporters of the Algerian cause, from the porteurs de valises—supporters of the Front de Libération Nationale who risked their own safety by carrying documents and money in support of the movement—to strictly intellectual critics of colonialism. He incurred the anger of the Algerian nationalists when he wrote that “to demand national independence for Algeria is a purely emotional response to the situation. There has never been an Algerian nation.” Equally provocative, in the context of 1958, was his claim that the French in Algeria were, after 130 years of colonization, “an indigenous population in the full sense of the word.”

It’s important to say what Algerian Chronicles is not. Camus does not take on the structures of colonial domination. Among his contemporaries, Sartre, in “Colonialism Is