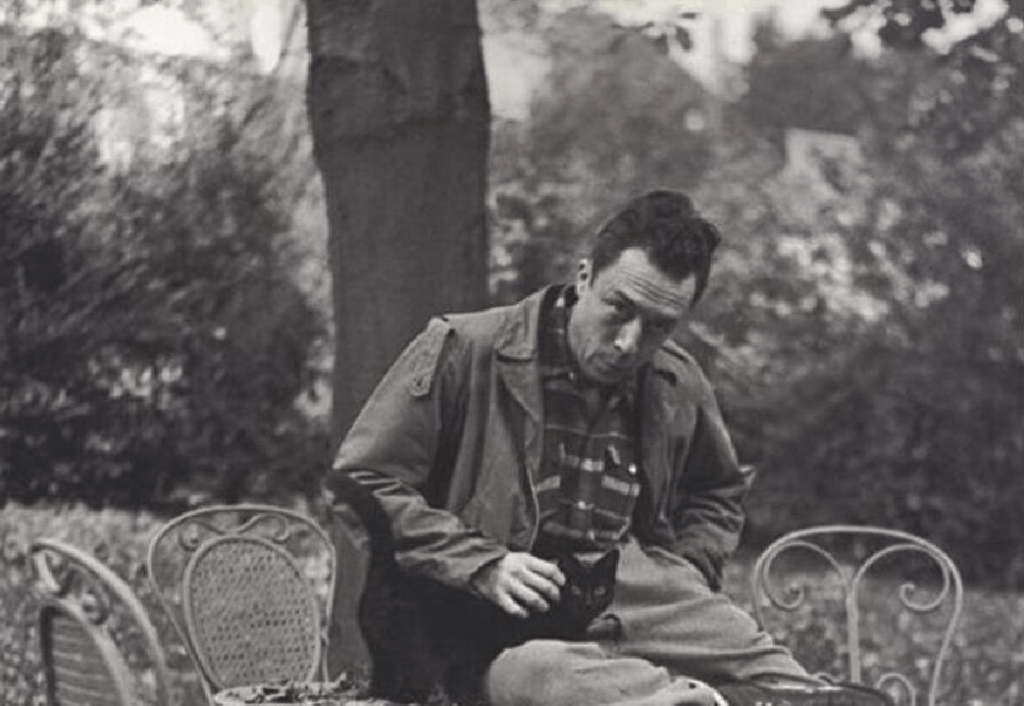

Defense of Freedom, Albert Camus

Contents

Defense of Freedom

Bread and Freedom

Homage to an Exile

Defense of Freedom

BREAD AND FREEDOM

(Speech given at the Labor Exchange of Saint-Etienne on 10 May 1953)

IF WE add up the examples of breach of faith and extortion that have just been pointed out to us, we can foresee a time when, in a Europe of concentration camps, the only people at liberty will be prison guards who will then have to lock up one another. When only one remains, he will be called the “supreme guard,” and that will be the ideal society in which problems of opposition, the headache of all twentieth-century governments, will be settled once and for all.

Of course, this is but a prophecy and, although governments and police forces throughout the world are striving, with great good will, to achieve such a happy situation, we have not yet gone that far. Among us, for instance, in Western Europe, freedom is officially approved. But such freedom makes me think of the poor female cousin in certain middle-class families. She has become a widow; she has lost her natural protector. So she has been taken in, given a room on the top floor, and is welcome in the kitchen.

She is occasionally paraded publicly on Sunday, to prove that one is virtuous and not a dirty dog. But for everything else, and especially on state occasions, she is requested to keep her mouth shut. And even if some policeman idly takes liberties with her in dark corners, one doesn’t make a fuss about it, for she has seen such things before, especially with the master of the house, and, after all, it’s not worth getting in bad with the legal authorities.

In the East, it must be admitted, they are more forthright. They have settled the business of the female cousin once and for all by locking her up in a closet with two solid bolts on the door. It seems that she will be taken out fifty years from now, more or less, when the ideal society is definitively established. Then there will be celebrations in her honor. But, in my opinion, she may then be somewhat moth-eaten, and I am very much afraid that it may be impossible to make use of her.

When we stop to think that these two conceptions of freedom, the one in the closet and the other in the kitchen, have decided to force themselves on each other and are obliged in all that hullabaloo to reduce still further the female cousin’s activity, it will be readily seen that our history is rather one of slavery than of freedom and that the world we live in is the one that has just been described, which leaps out at us from the newspaper every morning to make of our days and our weeks a single day of revolt and disgust.

The simplest, and hence most tempting, thing is to blame governments or some obscure powers for such naughty behavior. Besides, it is indeed true that they are guilty and that their guilt is so solidly established that we have lost sight of its beginnings. But they are not the only ones responsible. After all, if freedom had always had to rely on governments to encourage her growth, she would probably be still in her infancy or else definitively buried with the inscription “another angel in heaven.”

The society of money and exploitation has never been charged, so far as I know, with assuring the triumph of freedom and justice. Police states have never been suspected of opening schools of law in the cellars where they interrogate their subjects. So, when they oppress and exploit, they are merely doing their job, and whoever blindly entrusts them with the care of freedom has no right to be surprised when she is immediately dishonored. If freedom is humiliated or in chains today, it is not because her enemies had recourse to treachery. It is simply because she has lost her natural protector. Yes, freedom is widowed, but it must be added because it is true: she is widowed of all of us.

Freedom is the concern of the oppressed, and her natural protectors have always come from among the oppressed. In feudal Europe the communes maintained the ferments of freedom; those who assured her fleeting triumph in 1789 were the inhabitants of towns and cities; and since the nineteenth century the workers’ movements have assumed responsibility for the double honor of freedom and justice, without ever dreaming of saying that they were irreconcilable. Laborers, both manual and intellectual, are the ones who gave a body to freedom and helped her progress in the world until she has become the very basis of our thought, the air we cannot do without, that we breathe without even noticing it until the time comes when, deprived of it, we feel that we are dying.

And if freedom is regressing today throughout such a large part of the world, this is probably because the devices for enslavement have never been so cynically chosen or so effective, but also because her real defenders, through fatigue, through despair, or through a false idea of strategy and efficiency, have turned away from her. Yes, the great event of the twentieth century was the forsaking of the values of freedom by the revolutionary movement, the progressive retreat of socialism based on freedom before the attacks of a Caesarian and military socialism. Since that moment a certain hope has disappeared from the world and a solitude has begun for each and every free man.

When, after Marx, the rumor began to spread and gain strength that freedom was a bourgeois hoax, a single word was misplaced in that definition, and we are still paying for that mistake through the convulsions of our time. For it should have been said merely that bourgeois freedom was a hoax—and not all freedom. It should have been said simply that bourgeois freedom was not freedom or, in the best of cases, was not yet freedom. But that there were liberties to be won and never to be relinquished again. It is quite true that there is no possible freedom for the man tied to his lathe all day long who, when evening comes, crowds into a single room with his family. But this fact condemns a class, a society and the slavery it assumes, not freedom itself, without which the poorest among us cannot get along.

For even if society were suddenly transformed and became decent and comfortable for all, it would still be a barbarous state unless freedom triumphed. And because bourgeois society talks about freedom without practicing it, must the world of workers also give up practicing it and boast merely of not talking about it? Yet the confusion took place and in the revolutionary movement freedom was gradually condemned because bourgeois society used it as a hoax. From a justifiable and healthy distrust of the way that bourgeois society prostituted freedom, people came to distrust freedom itself. At best, it was postponed to the end of time, with the request that meanwhile it be not talked about. The contention was that we needed justice first and that we would come to freedom later on, as if slaves could ever hope to achieve justice.

And forceful intellectuals announced to the worker that bread alone interested him rather than freedom, as if the worker didn’t know that his bread depends in part on his freedom. And, to be sure, in the face of the prolonged injustice of bourgeois society, the temptation to go to such extremes was great. After all, there is probably not one of us here who, either in deed or in thought, did not succumb. But history has progressed, and what we have seen must now make us think things over. The revolution brought about by workers succeeded in 1917 and marked the dawn of real freedom and the greatest hope the world has known.

But that revolution, surrounded from the outside, threatened within and without, provided itself with a police force. Inheriting a definition and a doctrine that pictured freedom as suspect, the revolution little by little became stronger, and the world’s greatest hope hardened into the world’s most efficient dictatorship. The false freedom of bourgeois society has not suffered meanwhile.

What was killed in the Moscow trials and elsewhere, and in the revolutionary camps, what is assassinated when in Hungary a railway worker is shot for some professional mistake, is not bourgeois freedom but rather the freedom of 1917. Bourgeois freedom can meanwhile have recourse to all possible hoaxes. The trials and perversions of revolutionary society furnish it at one and the same time with a good conscience and with arguments against its enemies.

In conclusion, the characteristic of the world we live in is just that cynical dialectic which sets up injustice against enslavement while strengthening one by the other. When we admit to the palace of culture Franco, the friend of Goebbels and of Himmler—Franco, the real victor of the Second World War—to those who protest that the rights of man inscribed in the charter of UNESCO are turned to ridicule every day in Franco’s prisons we reply without smiling that Poland figures in UNESCO too and that, as far as public freedom is concerned, one is no better than the other.

An idiotic argument, of course! If you were so unfortunate as to marry off your elder daughter to a sergeant in a battalion of ex-convicts, this is no reason why you should marry off her younger sister to the most elegant