Cross Purpose, The Misunderstanding, Albert Camus

The Misunderstanding

Characters in the Play

Act I

Act II

Act III

THE MISUNDERSTANDING

A PLAY IN THREE ACTS

To my friends of the THÉÂTRE DE L’ÉQUIPE

CHARACTERS IN THE PLAY

THE OLD MANSERVANT

MARTHA

THE MOTHER

JAN

MARIA

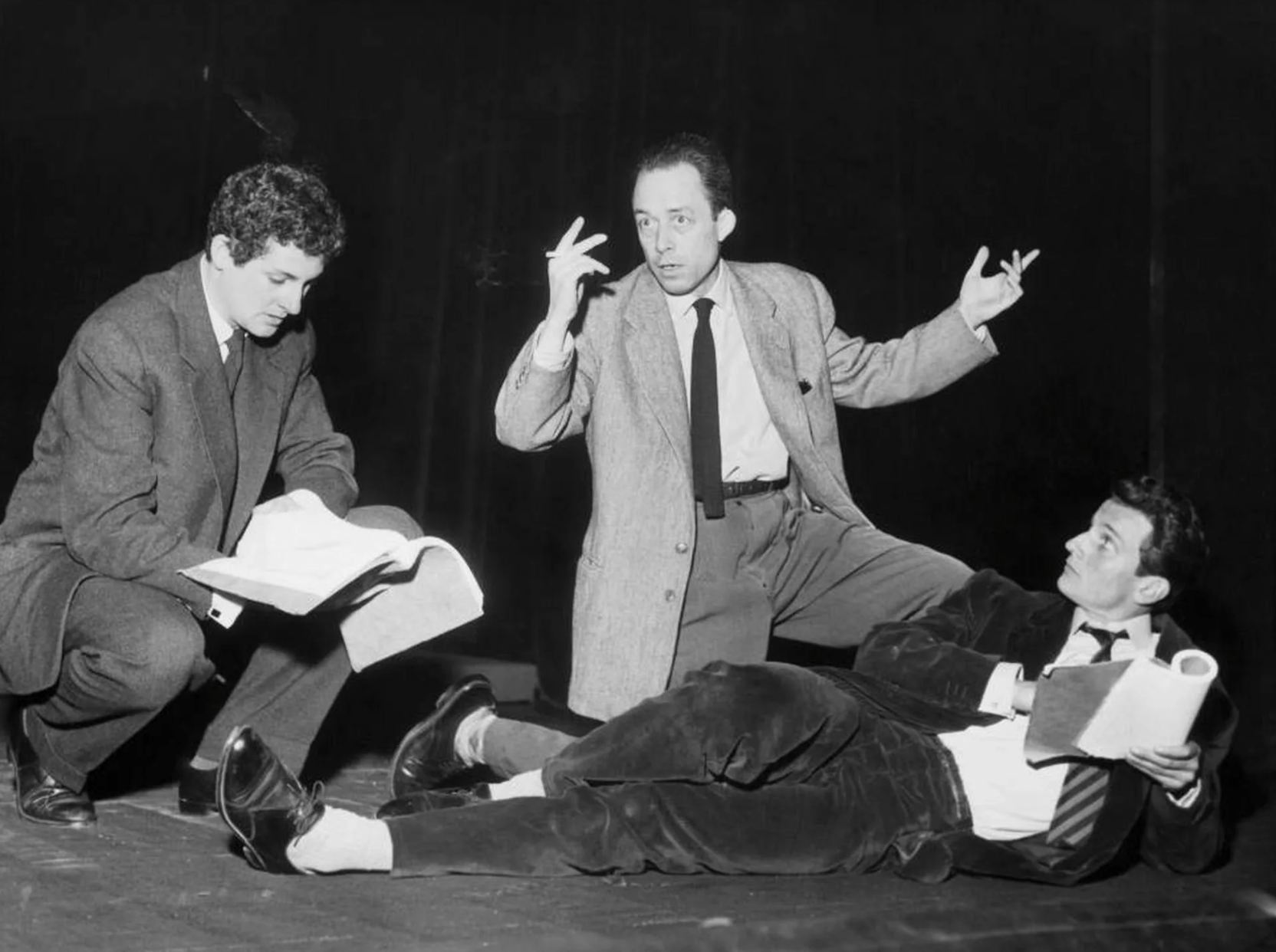

Cross Purpose, LE MALENTENDU (THE MISUNDERSTANDING) was presented for the first time at the THÉÂTRE DES MATHURINS, Paris, in 1944

ACT I

Noon. The clean, brightly lit public room of an inn.

Everything is very spick and span.

THE MOTHER: He’ll come back.

MARTHA: Did he tell you so?

THE MOTHER: Yes.

MARTHA: Alone?

THE MOTHER: That I can’t say.

MARTHA: He doesn’t look like a poor man.

THE MOTHER: No, and he never asked what our charges were.

MARTHA: A good sign, that. But usually rich men don’t travel alone. Really it’s that makes things so difficult. You may have to wait ages when you’re looking out for a man who is not only rich but quite alone.

THE MOTHER: Yes, we don’t get so many opportunities.

MARTHA: It means, of course, that we’ve had many slack times these last few years. This place is often empty. Poor people who stop here never stay long, and it’s mighty seldom rich ones come.

THE MOTHER: Don’t grumble about that, Martha. Rich people give a lot of extra work.

MARTHA [looking hard at her]: But they pay well. [A short silence.] Tell me, mother; what’s come over you? For some time I’ve noticed that you weren’t quite … quite your usual self.

THE MOTHER: I’m tired, my dear, that’s all. What I need is a long rest.

MARTHA: Listen, mother. I can take over the household work you’re doing now. Then you’ll have your days free.

THE MOTHER: That wasn’t quite the sort of rest I meant. Oh, I suppose it’s just an old woman’s fancy. All I’m longing for is peace—to be able to relax a little. [She gives a little laugh.] I know it sounds silly, Martha, but some evenings I feel almost like taking to religion.

MARTHA: You’re not so very old, mother; you haven’t come to that yet. And, anyhow, I should say you could do better.

THE MOTHER: Of course I was only joking, my dear. All the same … at the end of one’s life, it’s not a bad idea to take things easy. One can’t be always on the go, as you are, Martha. And it isn’t natural for a woman of your age, either. I know plenty of girls who were born the same year as you, and they think only of pleasure and excitements.

MARTHA: Their pleasures and excitements are nothing compared to ours, don’t you agree, mother?

THE MOTHER: I’d rather you didn’t speak of that.

MARTHA [thoughtfully]: Really one would think that nowadays some words burn your tongue.

THE MOTHER: What can it matter to you—provided I don’t shrink from acts? But that has no great importance. What I really meant was that I’d like to see you smile now and again.

MARTHA: I do smile sometimes, I assure you.

THE MOTHER: Really? I’ve never seen you.

MARTHA: That’s because I smile when I’m by myself, in my bedroom.

THE MOTHER [looking closely at her]: What a hard face you have, Martha!

MARTHA [coming closer; calmly]: Ah, so you don’t approve of my face?

THE MOTHER [after a short silence, still looking at her]: I wonder … Yes, I think I do.

MARTHA [emotionally]: Oh, mother, can’t you understand? Once we have enough money in hand, and I can escape from this shut-in valley; once we can say good-by to this inn and this dreary town where it’s always raining; once we’ve forgotten this land of shadows—ah, then, when my dream has come true, and we’re living beside the sea, then you will see me smile. Unfortunately one needs a great deal of money to be able to live in freedom by the sea. That is why we mustn’t be afraid of words; that is why we must take trouble over this man who’s come to stay here. If he is rich enough, perhaps my freedom will begin with him.

THE MOTHER: If he’s rich enough, and if he’s by himself.

MARTHA: That’s so. He has to be by himself as well. Did he talk much to you, mother?

THE MOTHER: No, he said very little.

MARTHA: When he asked for his room, did you notice how he looked?

THE MOTHER: No. My sight’s none too good, you know, and I didn’t really look at his face. I’ve learned from experience that it’s better not to look at them too closely. It’s easier to kill what one doesn’t know. [A short silence.] There! That should please you. You can’t say now that I’m afraid of words.

MARTHA: Yes, and I prefer it so. I’ve no use for hints and evasions. Crime is crime, and one should know what one is doing. And, from what you’ve just said, it looks as if you had it in mind when you were talking to that traveler.

THE MOTHER: No, I wouldn’t say I had it in mind—it was more from force of habit.

MARTHA: Habit? But you said yourself that these opportunities seldom come our way.

THE MOTHER: Certainly. But habit begins with the second crime. With the first nothing starts, but something ends. Then, too, while we have had few opportunities, they have been spread out over many years, and memory helps to build up habits. Yes, it was force of habit that made me keep my eyes off that man when I was talking to him, and, all the same, convinced me he had the look of a victim.

MARTHA: Mother, we must kill him.

THE MOTHER [in a low tone]: Yes, I suppose we’ll have to.

MARTHA: You said that in a curious way.

THE MOTHER: I’m tired, that’s all. Anyhow, I’d like this one to be the last. It’s terribly tiring to kill. And, though really I care little where I die—beside the sea or here, far inland—I do hope we will get away together, the moment it’s over.

MARTHA: Indeed we shall—and what a glorious moment that will be! So, cheer up, mother, there won’t be much to do. You know quite well there’s no question of killing. He’ll drink his tea, he’ll go to sleep, and he’ll be still alive when we carry him to the river. Some day, long after, he will be found jammed against the weir, along with others who didn’t have his luck and threw themselves into the water with their eyes open. Do you remember last year when we were watching them repair the sluices, how you said that ours suffered least, and life was crueler than we? So don’t lose heart, you’ll be having your rest quite soon and I’ll be seeing what I’ve never seen.

THE MOTHER: Yes, Martha, I won’t lose heart. And it was quite true, what you said about “ours.” I’m always glad to think they never suffered. Really, it’s hardly a crime, only a sort of intervention, a flick of the finger given to unknown lives. And it’s also quite true that, by the look of it, life is crueler than we. Perhaps that is why I can’t manage to feel guilty. I can only just manage to feel tired.

[The OLD MANSERVANT comes in. He seats himself behind the bar and remains there, neither moving nor speaking, until JAN’S entrance.]

MARTHA: Which room shall we put him in?

THE MOTHER: Any room, provided it’s on the first floor.

MARTHA: Yes, we had a lot of needless trouble last time, with the two flights of stairs. [For the first time she sits down.] Tell me, mother, is it true that down on the coast the sand’s so hot it scorches one’s feet?

THE MOTHER: As you know, Martha, I’ve never been there. But I’ve been told the sun burns everything up.

MARTHA: I read in a book that it even burns out people’s souls and gives them bodies that shine like gold but are quite hollow, there’s nothing left inside.

THE MOTHER: Is that what makes you want to go there so much?

MARTHA: Yes, my soul’s a burden to me, I’ve had enough of it. I’m eager to be in that country, where the sun kills every question. I don’t belong here.

THE MOTHER: Unfortunately we have much to do beforehand. Of course, when it’s over, I’ll go there with you. But I am not like you; I shall not have the feeling of going to a place where I belong. After a certain age one knows there is no resting place anywhere. Indeed there’s something to be said for this ugly brick house we’ve made our home and stocked with memories; there are times when one can fall asleep in it. But, naturally it would mean something, too, if I could have sleep and forgetfulness together. [She rises and walks toward the door.] Well, Martha, get everything ready. [Pauses.] If it’s really worth the effort.

[MARTHA watches her go out. Then she, too, leaves by another door. For some moments only the OLD MANSERVANT is on the stage. JAN enters, stops, glances round the room, and sees the old man sitting behind the counter.]

JAN: Nobody here? [The old man gazes at him, rises, crosses the stage, and goes out. MARIA enters. JAN swings round on her.] So you followed me!

MARIA: Forgive me—I couldn’t help it. I may not stay long. Only please let me look at the place where I’m leaving you.

JAN: Somebody may come, and your being here will upset all my plans.

MARIA: Do please let us take the chance of someone’s coming and my telling who you are. I know you don’t want it, but—[He turns away fretfully. A short silence. MARIA is examining the room.] So this is the place?

JAN: Yes. That’s the door I went out by, twenty