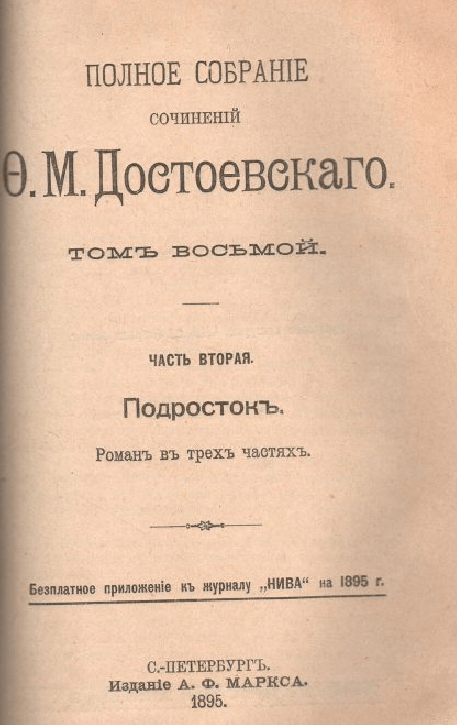

The Adolescent (The Raw Youth) Fyodor Dostoevsky

The Raw Youth

Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Conclusion

LIST OF PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS

Russian names are composed of first name, patronymic (from the father’s first name), and family name. Formal address requires the use of first name and patronymic; diminutives (Arkasha, Lizochka, Sonya) are commonly used among family and intimate friends. The following is a list of the principal characters in The Adolescent, with diminutives and epithets. In Russian pronunciation, the stressed vowel is always long and unstressed vowels are very short.

Dolgorúky, Arkády Makárovich (Arkásha, Arkáshenka, Arkáshka): the adolescent, “author” of the novel.

Makár Ivánovich: his legal father.

Sófya Andréevna (Sónya, Sophie): his mother.

Lizavéta Makárovna (Líza, Lízochka, Lizók): his sister.

Versílov, Andréi Petróvich: natural father of Arkady and Liza.

Ánna Andréevna: Versilov’s daughter by his first marriage.

Andréi Andréevich: the kammerjunker, Versilov’s son by his first marriage.

Akhmákov, Katerína Nikoláevna (Kátya): young widow of General Akhmakov.

Lýdia (no patronymic): her stepdaughter. Sokólsky, Prince Nikolái Ivánovich: the old prince, Mme. Akhmakov’s father.

Prutkóv, Tatyána Pávlovna: the “aunt,” friend of the Versilov family.

Sokólsky, Prince Sergéi Petróvich (Seryózha): the young prince, no relation to Prince Nikolai Ivanovich.

Lambért, Mauríce: schoolfriend of Arkady’s, a Frenchman.

Verdáigne, Alphonsíne de (Alphonsina, Alphonsinka): Lambert’s girlfriend.

Dárya Onísimovna (no family name; her name changes to Nastásya Egórovna in Part Three): mother of the young suicide Ólya (diminutive of Ólga).

Vásin, Grísha (diminutive of Grigóry; no patronymic): friend of Arkady’s.

Stebelkóv (no first name or patronymic): Vasin’s stepfather. Pyótr Ippolítovich (no last name): Arkady’s landlord. Nikolái Semyónovich (no last name): Arkady’s tutor in Moscow.

Márya Ivánovna: Nikolai Semyonovich’s wife. Trishátov, Pétya [i.e., Pyótr] (no patronymic): the pretty boy. Andréev, Nikolái Semyónovich: le grand dadais.

Semyón Sídorovich (Sídorych; no last name): the pockmarked one.

THE TOPOGRAPHY OF ST. PETERSBURG

The city was founded in 1703 by a decree of the emperor Peter the Great and built on the delta of the river Neva, which divides into three main branches – the Big Neva, the Little Neva, and the Nevka – as it flows into the Gulf of Finland. On the left bank of the Neva is the city center, where the Winter Palace, the Senate, the Admiralty, the Summer Garden, the theaters, and the main thoroughfares such as Nevsky Prospect, Bolshaya Millionnaya, and Bolshaya Morskaya are located. On the right bank of the Neva before it divides is the area known as the Vyborg side; the right bank between the Nevka and the Little Neva is known as the Petersburg side, where the Peter and Paul Fortress, the oldest structure of the city, stands; between the Little Neva and the Big Neva is Vassilievsky Island. To the south, some fifteen miles from the city, is the suburb of Tsarskoe Selo, where the empress Catherine the Great built an imposing palace and many of the gentry had summer houses.

PART ONE

Chapter One

I

UNABLE TO RESTRAIN myself, I have sat down to record this history of my first steps on life’s career, though I could have done as well without it. One thing I know for certain: never again will I sit down to write my autobiography, even if I live to be a hundred. You have to be all too basely in love with yourself to write about yourself without shame. My only excuse is that I’m not writing for the same reason everyone else writes, that is, for the sake of the reader’s praises. If I have suddenly decided to record word for word all that has happened to me since last year, then I have decided it as the result of an inner need: so struck I am by everything that has happened. I am recording only the events, avoiding with all my might everything extraneous, and above all—literary beauties.

A literary man writes for thirty years and in the end doesn’t know at all why he has written for so many years. I am not a literary man, do not want to be a literary man, and would consider it base and indecent to drag the insides of my soul and a beautiful description of my feelings to their literary marketplace. I anticipate with vexation, however, that it seems impossible to do entirely without the description of feelings and without reflections (maybe even banal ones): so corrupting is the effect of any literary occupation on a man, even if it is undertaken only for oneself. The reflections may even be very banal, because something you value yourself will quite possibly have no value in a stranger’s eyes. But this is all an aside. Anyhow, here is my preface; there won’t be anything more of its kind. To business; though there’s nothing trickier than getting down to some sort of business—maybe even any sort.

II

I BEGIN, THAT IS, I would like to begin my notes from the nineteenth of September last year, that is, exactly from the day when I first met . . .

But to explain whom I met just like that, beforehand, when nobody knows anything, would be banal; I suppose even the tone is banal: having promised myself to avoid literary beauties, I fall into those beauties with the first line. Besides, in order to write sensibly, it seems the wish alone is not enough. I will also observe that it seems no European language is so difficult to write in as Russian. I have now reread what I’ve just written, and I see that I’m much more intelligent than what I’ve written. How does it come about that what an intelligent man expresses is much stupider than what remains inside him? I’ve noticed that about myself more than once in my verbal relations with people during this last fateful year and have suffered much from it.

Though I’m starting with the nineteenth of September, I’ll still put in a word or two about who I am, where I was before then, and therefore also what might have been in my head, at least partly, on that morning of the nineteenth of September, so that it will be more understandable to the reader, and maybe to me as well.

III

I AM A HIGH-SCHOOL graduate, and am now going on twenty-one. My last name is Dolgoruky, and my legal father is Makar Ivanovich Dolgoruky,1 a former household serf of the Versilov family. Thus I’m a legitimate, though in the highest degree illegitimate, son, and my origin is not subject to the slightest doubt. It happened like this: twenty-two years ago, the landowner Versilov (it’s he who is my father), twenty-five years of age, visited his estate in Tula province. I suppose at that time he was still something rather faceless.

It’s curious that this man, who impressed me so much ever since my childhood, who had such a capital influence on my entire cast of mind and has maybe even infected my whole future with himself for a long time to come—this man even now remains in a great many ways a complete riddle to me. But of that, essentially, later. You can’t tell it like that. My whole notebook will be filled with this man as it is.

He had become a widower just at that time, that is, in the twenty-fifth year of his life. He had married someone from high society, but not that rich, named Fanariotov, and had had a son and a daughter by her. My information about this spouse who abandoned him so early is rather incomplete and lost among my materials; then, too, much about the private circumstances of Versilov’s life has escaped me, so proud he always was with me, so haughty, closed, and negligent, despite his moments of striking humility, as it were, before me. I mention, however, so as to mark it for the future, that he ran through three fortunes in his life, even quite big ones, some four hundred thousand in all, and maybe more. Now, naturally, he hasn’t got a kopeck . . .

He came to the country then, “God knows why”—at least that was how he put it to me later. His little children were, as usual, not with him but with some relations; that was what he did with his children, legitimate and illegitimate, all his life. There was a significant number of household serfs on this estate; among them was the gardener Makar Ivanovich Dolgoruky. I will add here, to be rid of it once and for all: rarely can anyone have been so thoroughly angered by his last name as I was throughout my whole life.

That was stupid, of course, but it was so. Each time I entered some school or met persons to whom I owed an accounting because of my age, in short, every little teacher, tutor, inspector, priest, anybody you like, they would ask my last name and, on hearing that I was Dolgoruky, would inevitably find it somehow necessary to add:

“Prince Dolgoruky?”

And each time I was obliged to explain to all these idle people:

“No, simply Dolgoruky.”

This simply began, finally, to drive me out of my mind. I will note with that, as a phenomenon, that I do not recall a single exception: everybody asked. Some of them seemingly had no need at all to ask; who the devil could have had any need of it, I’d like to know? But everybody asked, everybody to a man. Hearing that I was simply Dolgoruky, the asker ordinarily measured me with a dull and stupidly indifferent look, indicating thereby that he did not know himself why he had asked, and walked away.

My schoolmates were the most insulting. How does a schoolboy question a newcomer? A lost and abashed newcomer, on the first day he enters school (no matter what kind), is a common victim: he