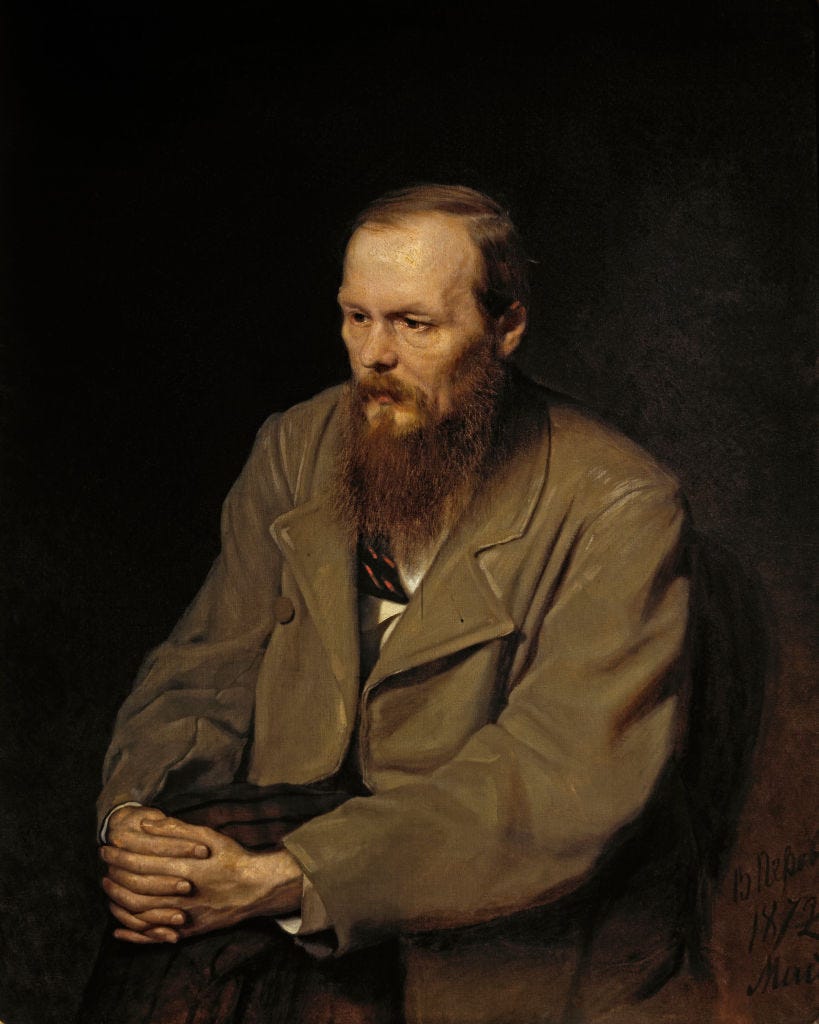

The Boy at Christ’s Christmas Party, Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky

The Boy at Christ’s Christmas Party

But I am a novelist and one ‘story,’ it seems, I made up myself. Why do I say ‘it seems’ when I know very well that I made it up? Yet I keep imagining that it really happened somewhere, sometime, and happened precisely on Christmas Eve in a certain huge city during a terrible cold spell.

I dreamed there was a boy – still very small, about six or even younger – who awoke one morning in the damp and cold cellar where he lived. He was wearing a wretched wrapper of some sort and he was trembling. His breath escaped in a white cloud and, while he sat, bored, in the corner on a trunk, he would let this white vapour out of his mouth and amuse himself by watching it billow up. But he was very hungry. Several times that morning he had approached the bed on which his sick mother lay on a mattress as thin as a pancake, a bundle beneath her head to serve as a pillow. How did she come to be here?

Probably she had come with her boy from another city and suddenly fell ill. The landlady of this wretched tenement had been picked up by the police two days ago; the other tenants had all gone off, it being the holiday season, leaving but one dodger who had been lying in a drunken stupor for the last twenty-four hours, having been unable even to wait for the holiday. In another corner of the room an old woman of eighty groaned with rheumatism. She had once worked somewhere as a children’s nurse but now was dying alone, moaning, grumbling, and complaining at the boy so that he had become frightened of approaching her corner.

In the entry way he managed to find some water to quench his thirst, but nowhere could he find a crust of bread; again and again he went to wake his mother. At last he grew frightened in the darkness; the evening was well advanced, but still no candle had been lit. When he felt his mother’s face he was surprised that she made no movement and had become as cold as the wall. ‘And it’s dreadful cold in here,’ he thought. He stood for a time, absently resting his hand on the dead woman’s shoulder; then he breathed on his fingers to warm them, and suddenly his wandering fingers felt his cap that lay on the bed; quietly he groped his way out of the cellar. He would have gone even before but he was afraid of the big dog that howled all day long by the neighbour’s door on the stairway above. But the dog was no longer there, and in a thrice he was out on the street.

Heavens, what a city! He had never seen anything like it before. In the place he had come from there was such gloomy darkness at night, with only one lamppost for the whole street. The tiny wooden houses were closed in by shutters; as soon as it got dark you wouldn’t see a soul on the street; everyone would lock themselves in their houses, only there would be huge packs of dogs – hundreds and thousands of dogs – howling and barking all night.

Still, it was so nice and warm there, and there’d be something to eat; but here – Dear Lord, if only there was something to eat! And what a rattling and a thundering there was here, so much light, and so many people, horses, and carriages, and the cold – oh, the cold! Frozen vapor rolls from the overdriven horses and streams from their hot, panting muzzles; their horseshoes ring against the paving stones under the fluffy snow, and everyone’s pushing each other, and, Oh Lord, I’m so hungry, even just a little bite of something, and all of a sudden my fingers are aching so. One of our guardians of the law passed by and averted his eyes so as not to notice the boy.

And here’s another street – look how wide it is! I’ll get run over here for sure. See how everyone’s shouting and rushing and driving along, and the lights – just look at them! Now what can this be? What a big window, and in the room behind the glass there’s a tree that stretches right up to the ceiling. It’s a Christmas tree, with oh, so many lights on it, so many bits of gold paper and apples; and there’s dolls and little toy horses all around it; children are running around the room, clean and dressed in nice clothes, laughing and playing, eating and drinking something. Look at that girl dancing with the boy, how fine she is! And you can even hear the music right through the glass.

The little boy looks on in amazement and even laughs; but now his toes are aching and his fingers are quite red; he can’t bend them any more, and it hurts when he tries to move them. The boy suddenly thought of how much his fingers hurt, and he burst into tears and ran off, and once more he sees a room through another window, and this one also has trees, but there are cakes on the tables, all sorts of cakes – almond ones, red ones, yellow ones; and four rich ladies are sitting there giving cakes to anyone who comes in. The door is always opening to let in all these fine people from the street.

The boy crept up, quickly pushed open the door, and went in. Heavens, how they shouted at him and waved him away! One of the ladies rushed up to him and shoved a kopeck in his hand; then she opened the door to let him out on the street again. How frightened he was! And the kopeck rolled right out of his hand and bounced down the stairs; he couldn’t bend his red fingers to hold on to it. The boy ran off as quickly as he could, but had no notion of where he was going. He felt like crying again, but he was afraid and just kept on running, breathing on his fingers.

And his heart ached because suddenly he felt so lonely and so frightened, and then – Oh, Lord! What’s happening now? There’s a crowd of people standing around gaping at something: behind the glass in the window there are three puppets, little ones dressed up in red and green and looking just like they were alive! One of them’s a little old man, sitting there like he’s playing on a big violin, and the others are standing playing on tiny fiddles, wagging their heads in time to the music and looking at one another; their lips are moving and they’re talking, really talking, only you can’t hear them through the glass.

At first the boy thought that they were alive, but when he finally realized that they were puppets he burst out laughing. He had never seen such puppets before and had no idea that such things existed! He still felt like crying, but it was so funny watching the puppets. Suddenly he felt someone grab him from behind: a big brute of a boy stood beside him and suddenly cracked him on the head, tore off his cap, and kicked at his legs. The boy fell down, and the people around him began shouting; he was struck with terror, jumped to his feet and ran off as fast as he could, wherever his legs would take him – through a gateway into a courtyard where he crouched down behind a pile of wood. ‘They won’t find me here, and it’s good and dark as well.’

He sat there, cowering and unable to catch his breath from fear, and then, quite suddenly, he felt so good: his hands and feet at once stopped aching and he felt as warm and cozy as if he were next to the stove. Then a shudder passed over him: ‘Why I almost fell asleep!’ How nice it would be to go to sleep here: ‘I’ll sit here for a bit and then go back to have a look at those puppets,’ he thought, and grinned as he recalled them. ‘Just like they were alive! . . .’ Then suddenly he heard his mother singing him a song as she bent over him. ‘Mamma, I’m going to sleep; oh, how nice it is to sleep here!’

Then a quiet voice whispered over him: ‘Come with me, son, to my Christmas party.’

At first he thought that it was still his mamma, but no – it couldn’t be. He couldn’t see who had called him, but someone bent over him and hugged him in the darkness; he stretched out his hand . . . and suddenly – what a light there was! And what a Christmas tree! It was more than a tree – he had never seen anything like it! Where can he be? Everything sparkles and shines and there are dolls everywhere – but no, they are all girls and boys, only they are so radiant and they all fly around him, kissing him, picking him up and carrying him off; but he’s flying himself; and he sees his mother looking at him and laughs joyously to her.

‘Mamma! Mamma! How lovely it is here, mamma!’ cries the boy; and he kisses the children again and wants at once to tell them about the puppets behind the glass. ‘Who are