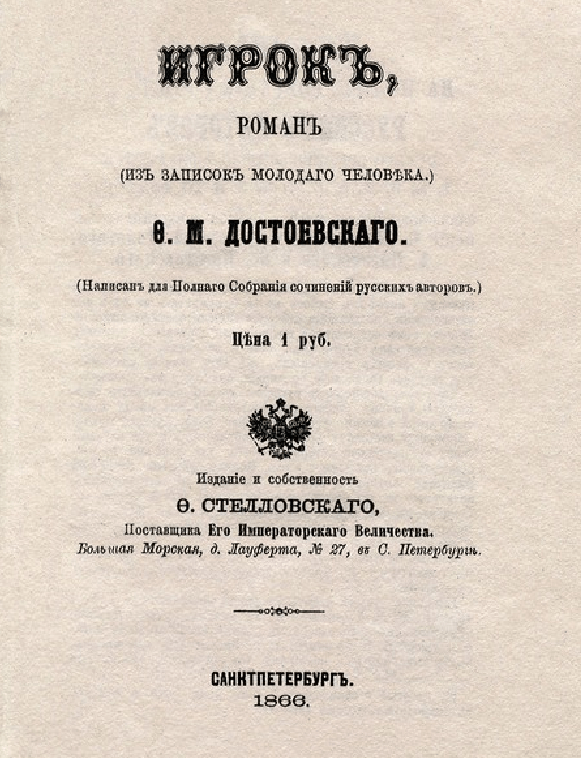

The Gambler, Fyodor Dostoevsky

(From a Young Man’s Notes)

The Gambler

Contents

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

I

At length I returned from two weeks leave of absence to find that my patrons had arrived three days ago in Roulettenberg. I received from them a welcome quite different to that which I had expected. The General eyed me coldly, greeted me in rather haughty fashion, and dismissed me to pay my respects to his sister. It was clear that from somewhere money had been acquired. I thought I could even detect a certain shamefacedness in the General’s glance.

Maria Philipovna, too, seemed distraught, and conversed with me with an air of detachment. Nevertheless, she took the money which I handed to her, counted it, and listened to what I had to tell. To luncheon there were expected that day a Monsieur Mezentsov, a French lady, and an Englishman; for, whenever money was in hand, a banquet in Muscovite style was always given.

Polina Alexandrovna, on seeing me, inquired why I had been so long away. Then, without waiting for an answer, she departed. Evidently this was not mere accident, and I felt that I must throw some light upon matters. It was high time that I did so.

I was assigned a small room on the fourth floor of the hotel (for you must know that I belonged to the General’s suite). So far as I could see, the party had already gained some notoriety in the place, which had come to look upon the General as a Russian nobleman of great wealth. Indeed, even before luncheon he charged me, among other things, to get two thousand-franc notes changed for him at the hotel counter, which put us in a position to be thought millionaires at all events for a week! Later, I was about to take Mischa and Nadia for a walk when a summons reached me from the staircase that I must attend the General.

He began by deigning to inquire of me where I was going to take the children; and as he did so, I could see that he failed to look me in the eyes. He wanted to do so, but each time was met by me with such a fixed, disrespectful stare that he desisted in confusion. In pompous language, however, which jumbled one sentence into another, and at length grew disconnected, he gave me to understand that I was to lead the children altogether away from the Casino, and out into the park. Finally his anger exploded, and he added sharply:

“I suppose you would like to take them to the Casino to play roulette? Well, excuse my speaking so plainly, but I know how addicted you are to gambling. Though I am not your mentor, nor wish to be, at least I have a right to require that you shall not actually compromise me.”

“I have no money for gambling,” I quietly replied.

“But you will soon be in receipt of some,” retorted the General, reddening a little as he dived into his writing desk and applied himself to a memorandum book. From it he saw that he had 120 roubles of mine in his keeping.

“Let us calculate,” he went on. “We must translate these roubles into thalers. Here—take 100 thalers, as a round sum. The rest will be safe in my hands.”

In silence I took the money.

“You must not be offended at what I say,” he continued. “You are too touchy about these things. What I have said I have said merely as a warning. To do so is no more than my right.”

When returning home with the children before luncheon, I met a cavalcade of our party riding to view some ruins. Two splendid carriages, magnificently horsed, with Mlle. Blanche, Maria Philipovna, and Polina Alexandrovna in one of them, and the Frenchman, the Englishman, and the General in attendance on horseback! The passers-by stopped to stare at them, for the effect was splendid—the General could not have improved upon it.

I calculated that, with the 4000 francs which I had brought with me, added to what my patrons seemed already to have acquired, the party must be in possession of at least 7000 or 8000 francs—though that would be none too much for Mlle. Blanche, who, with her mother and the Frenchman, was also lodging in our hotel. The latter gentleman was called by the lacqueys “Monsieur le Comte,” and Mlle. Blanche’s mother was dubbed “Madame la Comtesse.” Perhaps in very truth they were “Comte et Comtesse.”

I knew that “Monsieur le Comte” would take no notice of me when we met at dinner, as also that the General would not dream of introducing us, nor of recommending me to the “Comte.” However, the latter had lived awhile in Russia, and knew that the person referred to as an “uchitel” is never looked upon as a bird of fine feather. Of course, strictly speaking, he knew me; but I was an uninvited guest at the luncheon—the General had forgotten to arrange otherwise, or I should have been dispatched to dine at the table d’hote. Nevertheless, I presented myself in such guise that the General looked at me with a touch of approval; and, though the good Maria Philipovna was for showing me my place, the fact of my having previously met the Englishman, Mr. Astley, saved me, and thenceforward I figured as one of the company.

This strange Englishman I had met first in Prussia, where we had happened to sit vis-à-vis in a railway train in which I was travelling to overtake our party; while, later, I had run across him in France, and again in Switzerland—twice within the space of two weeks! To think, therefore, that I should suddenly encounter him again here, in Roulettenberg!

Never in my life had I known a more retiring man, for he was shy to the pitch of imbecility, yet well aware of the fact (for he was no fool). At the same time, he was a gentle, amiable sort of an individual, and, even on our first encounter in Prussia I had contrived to draw him out, and he had told me that he had just been to the North Cape, and was now anxious to visit the fair at Nizhni Novgorod. How he had come to make the General’s acquaintance I do not know, but, apparently, he was much struck with Polina. Also, he was delighted that I should sit next him at table, for he appeared to look upon me as his bosom friend.

During the meal the Frenchman was in great feather: he was discursive and pompous to every one. In Moscow too, I remembered, he had blown a great many bubbles. Interminably he discoursed on finance and Russian politics, and though, at times, the General made feints to contradict him, he did so humbly, and as though wishing not wholly to lose sight of his own dignity.

For myself, I was in a curious frame of mind. Even before luncheon was half finished I had asked myself the old, eternal question: “Why do I continue to dance attendance upon the General, instead of having left him and his family long ago?” Every now and then I would glance at Polina Alexandrovna, but she paid me no attention; until eventually I became so irritated that I decided to play the boor.

First of all I suddenly, and for no reason whatever, plunged loudly and gratuitously into the general conversation. Above everything I wanted to pick a quarrel with the Frenchman; and, with that end in view I turned to the General, and exclaimed in an overbearing sort of way—indeed, I think that I actually interrupted him—that that summer it had been almost impossible for a Russian to dine anywhere at tables d’hote. The General bent upon me a glance of astonishment.

“If one is a man of self-respect,” I went on, “one risks abuse by so doing, and is forced to put up with insults of every kind. Both at Paris and on the Rhine, and even in Switzerland—there are so many Poles, with their sympathisers, the French, at these tables d’hote that one cannot get a word in edgeways if one happens only to be a Russian.”

This I said in French. The General eyed me doubtfully, for he did not know whether to be angry or merely to feel surprised that I should so far forget myself.

“Of course, one always learns something everywhere,” said the Frenchman in a careless, contemptuous sort of tone.

“In Paris, too, I had a dispute with a Pole,” I continued, “and then with a French officer who supported him. After that a section of the Frenchmen present took my part. They did so as soon as I told them the story of how once I threatened to spit into Monsignor’s coffee.”

“To spit into it?” the General inquired with grave disapproval in his tone, and a stare, of astonishment, while the Frenchman looked at me unbelievingly.

“Just so,” I replied. “You must know that, on one occasion, when, for two days, I had felt certain that at any moment I might have to depart for Rome on business, I repaired to the Embassy of the Holy See in Paris, to have my passport visaed. There I encountered a sacristan of about fifty, and a man dry and cold of mien. After listening politely, but with great reserve, to my account of myself, this sacristan asked me to wait a little. I was in a great hurry to depart, but of