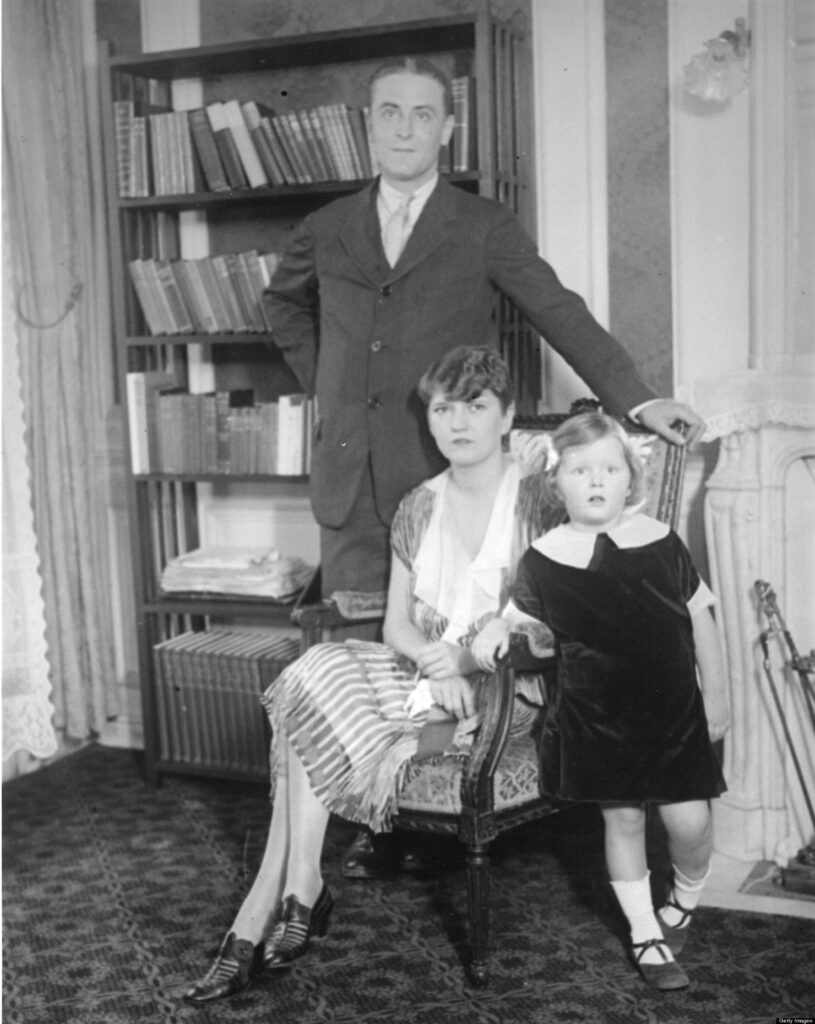

Day Off from Love, F. Scott Fitzgerald

On the afternoon they decided to marry they walked through the wood over damp, matted pine needles, and rather hesitantly Mary told him her plan.

“But now I see you every day,” Sam mourned.

“Only this last week,” Mary corrected him. “This was because we had to find out whether we could be together all the time and not—not—”

“Not drive each other mad,” he finished for her. “You wanted to see if you could take it.”

“No,” Mary objected, “Women don’t get bored the same way men do. They can sort of shut off their attention—but they always know when men are bored.

For instance, I knew a girl whose marriages lasted just so long—until she heard herself telling her husband a story she’d told him before. Then she went to Reno. We can’t have that—I’m sure to repeat myself. And we’ll both have to take it.”

She repeated even now a gesture that he loved, a sort of hitch at her skirt as if to say, “Tighten up your belt, baby. Let’s get going—to any pole.”

And Sam Baltjer wanted her to repeat on the same costume forever—the bright grey woolen dress with the scarlet zipper vest and lips to match.

Suddenly he guessed something. He was one of those men who seem eternally stolid, even unobserving—and then announce the score added up to the last digit.

“It’s because of your first marriage,” he said. “And I thought you never looked back.”

“Only for warnings.” Mary hesitated, “Pete and I were close like that—for three years—up to the day he died.

I was him and he was me—and at the end it didn’t work—I couldn’t die with him.” Again she hesitated, not sure of her ground. “I think a woman has to have some place to go inside herself—like a man’s ambition.”

So there was always to be a day off from love, a day in every week when they were to live separate geographical lives. And there was to be no talking over those days—no questions.

“Have you a little one hidden away?” Sam teased her. “A twin brother in the pen? Are you X9? Will I ever know?”

When they came to their destination, a party in one of those elaborate “cabins” that dot the Virginia foothills, Mary took off her scarlet vest and stood with her feet planted far apart before the great fire, telling the friends of her youth she was going to be married again.

She wore a silver belt with stars cut out of it, so that the stars were there and not quite there—and watching them Sam knew that he had not quite found her yet.

He wished for a moment that he were not so entirely successful nor Mary so desirable—wished that they were both a little broken and would want to cling together.

All the evening he felt a little sad watching the intangible stars as they moved here and there about the big rooms.

Mary was twenty-four. She was a professor’s daughter with the glowing exterior of a chorus girl—bronze hair and blue green eyes and a perpetual high flush that she was almost ashamed of.

The contrast between her social and physical equipment had set her many problems in the little college town.

She had married a professor whom there was no special reason for marrying and made a go of it—so much so that she had come near to dying with him, and only after two years had found the nights unhaunted and the skies blue.

But now marrying the exceptional young Baetjer, who was reorganizing coal properties just over the West Virginia line, seemed as natural as breathing.

The materials are all here, she knew, weighing things in her two handed way, and love is what you make of it.

The next Tuesday too she went to the mountain village, a county seat—a court house square with its cast iron Confederate soldier and a movie house, its population male and female in blue denim and the blue ridge rising as a back-drop on three sides.

This time she felt she had rather exhausted its possibilities—the purely physical side of her disappearance act would be when Sam took his seat in Congress this fall.

Once the little town had been a health center in a small way. There was a sanitarium on a hillside above and a little higher up the central building of what in 1929 was to have been a resort hotel.

She asked about it and was told that all the beds had been stolen, the furniture disappeared little by little, and looking again at the white shell in its magnificent location she drove up there idly in the late afternoon.

“—anyhow in the opinion of a poor widow woman,” she told the stranger up at Simpson’s Folly.

“In theory,” said the stranger, “But in theory this fellow Simpson could have made this the greatest resort hotel in the country.”

“There was the depression,” said Mary, looking around at the empty shell, high on its crag—a shell from which the mountaineers had long removed even the plumbing.

“You had your depression,” ventured the stranger, “and look at you now, as full of belief and hope as if it was all a matter of trying.

Why on your first day off—even before you’re married you meet a man, or the remnants of one. Just suppose we fell in love and you met me up here every week.

Then that day would grow more important than all the six days you spent with him. Then where’s your plan?”

They sat with their legs hung over a cracking balustrade. A spring wind was sweeping up warm from the valley and Mary let her heels swing with it against the limestone.

“I’ve told you an awful lot,” she said.

“You see—you’re interested. Already I’m the man you told a lot to. That’s a dangerous situation—to start out with a trust that people spend weeks working up to.”

“I’ve been coming up here to think for ten years,” she protested. “It’s the wind I’m talking to.”

“I suppose so,” he admitted. “It’s a hell of a good wind to sass—especially at night.”

“Do you live up here?” she asked in surprise.

“No—I’m visiting,” he answered hesitantly. “I’m paying a visit to a young man.”

“I didn’t know anyone lived here.”

“No one does—the young man is—or rather was myself.”

He broke off. “There’s a storm coming.”

Mary looked at him curiously. He was in his middle thirties and all of six feet four, a gaunt man with a slow way of talking.

He wore high-laced hunting boots and a chamy windbreaker that matched his brown rather ruthless eyes. About his face was some of that cadaverous look that lingers after a long illness and he lit a cigarette with unsteady fingers.

Ten minutes later he said:

“Your car won’t start and it’s a four hour job. You can coast down to the garage at the foot of the hill and then I’ll drive you into a town.”

They were quiet on the way in. A day of deliberately absenting herself turned out to be a long time, and she felt a twinge of doubt about the whole plan.

Even now as they drove along the principal street toward her father’s house it was only six o’clock with an evening to dispose of.

But she toughened herself—the first day was the hardest. She even kept an eye on the sidewalks with the mischievous hope that Sam would see her. The stranger at least had a hint of mystery.

“Pull over to the curb,” she said suddenly. Just ahead of them she had seen Sam’s roadster slowing up. And as both cars stopped she perceived that Sam was not alone.

“Yonder is my love,” she said to the stranger. “He seems to be having a day off too.”

He looked obediently.

“The pretty girl with him is Linda Newbold,” said Mary. “She is twenty and she made a great play for him a month ago.”

“You’re not disturbed?” the stranger asked curiously.

She shook her head.

“They left jealousy out of me. Probably gave me a big dose of conceit instead.”

This fragment is not dated, presumably it has been written in summer/fall of 1936. Across the top of the first page there written in pencil, in hand: “The trouble is of course that I forgot the real idea—this is Nora, or the world, looking at me.” There also exists a short manuscript fragment for this idea:

(Cheerful Title)

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The people who gave that party receive a fraction of a million from a small article you use every day. It is something that mankind did well enough without until ten years ago-but now finds indispensable. Guess again.

The guest of honor, Lisa, wore a silver belt with stars cut out of it. She wore a bright grey woolen dress with a red zipper vest and lips to match.

Her hair was dark gold and quiet (dark dull gold) and her voice sounded quiet but all her instincts were rowdy and she functioned in high gear amidst all confusions.

She was offered the crown at any gathering but she always mislaid it or wore it rakishly over one year.

Ike Blackford, whom she was to marry in a few months-his first, her second-stopped at the steps of the house and drew her up to him through the cool damp air of the pine grove.

Inside an orchestra was playing “Lovely to Look At,” molto con brio.

“Don’t circulate around,” he whispered into her cheek. “Stay beside me-in two hours I’ll be on my way.” Her arms promised. Then she gathered up all she could of the outdoors in