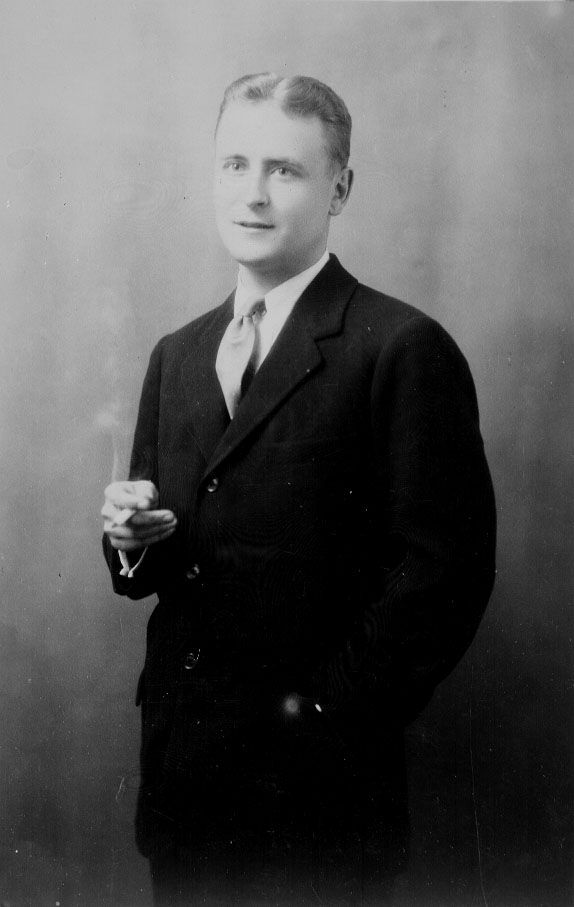

Dentist Appointment, F. Scott Fitzgerald

Written in 1937, an early version of “The End of Hate”story.

I

The buggy progressed at a tired trot and its two occupants, up since dawn, were as weary as their horses when they turned down the pike toward Washington.

The girl was tawny and lovely—despite July she wore a light blue dress of bombazine cloth and because of this she had listened politely to her brother’s strictures during the drive down: nurses in Washington hospitals did not dress like women of the world.

Josie was saddened for it was the first really grown-up costume she had ever owned.

She came of strict stock, but many youths at home had observed the charming glow of her person since she turned twelve and she had prepared for this trip as if she were going to a party.

“Is it still Maryland, brother?” She dug him with the handle of the buggy whip, and Captain Doctor Pilgrim came alive.

“Why—we’re approaching the District of Columbia—unless you’ve turned us around. We’ll stop and get water at this farmhouse just ahead.

And, Josie, don’t be too sweet with these people down here—They’re almost all secesh, and if you’re nice to them they take advantage of it and get haughty.”

The Pilgrims were possibly the only people in the vicinity who did not know that this part of Maryland was suddenly in Confederate hands.

To ease the pressure on Lee’s army at Petersburg, General Early had marched his corps up the Shenandoah Valley to make a last desperate threat at the capital.

After throwing a few shells into the suburbs, he learned of Federal rein for cements and turned his weary columns about for the march back into Virginia.

His last infantry had scarcely slogged along this very pike, leaving a stubborn dust, and Josie was rather puzzled by a number of what seemed to be armed tramps who limped past them.

Also there was something about the two men galloping toward the carriage that made her ask with a certain alarm, “What are those men, brother? Secesh?”

To Josie, or anyone who had not been to the front, it would have been difficult to place these men as soldiers—soldiers—Tib Dulany, who had once contributed occasional verse to the Lynchburg Courier, wore a hat that that had been white, a butternut coat, blue pants that had been issued to a Union trooper, and a cartridge belt stamped C.S.A.

All that the two riders had in common were their fine new carbines captured last week from Pleasanton’s cavalry. They came up beside the buggy in a whirl of dust and Tib saluted the doctor.

“Hi there, Yank!”

“We want to get some water,” said Josie haughtily to the handsomest young man. Then suddenly she saw that Captain Doctor Pilgrim’s hand was at his holster, but immobile—the second rider was holding a carbine three feet from his heart.

Almost painfully, Captain Pilgrim raised his arms.

“What is this—a raid?” he demanded.

Josie felt a hand reaching about her and shrank forward; Tib was taking her brother’s revolver.

“What is this?” repeated Dr. Pilgrim. “Are you guerillas?”

“Who are you?” the riders demanded. Without waiting for an answer Tib said “Young lady, turn in yonder at the farmhouse. You can get water there.”

He realised suddenly that she was lovely, that she was frightened and brave, and he added: “Nobody’s going to hurt you. We just aiming to detain you a little.”

“Will you tell me who you are?” Captain Pilgrim demanded.

“Cultivate calm!” Tib advised him. “You’re inside Lee’s lines now.”

“Lee’s lines!” Captain Pilgrim cried. “You think every time you Mosby murderers come out of your hills and cut a telegraph—”

The team, barely started, jolted to a stop—the second trooper had grabbed the reins, and turned black eyes upon the northerner.

“One word more about Mosby and I’ll clean your little old face with dandelions.”

“The officer isn’t informed of the news, Wash,” said Tib. “He doesn’t know he’s a prisoner of the Army of Northern Virginia.”

Captain Pilgrim looked at them incredulously; Wash released the reins and they drove to the farmhouse.

Only as the foliage parted and he saw two dozen horses attended by grey-clad orderlies, did he realize that his information was indeed several days behind.

“Is Lee’s army here?”

“You didn’t know? Why, right now Abe Lincoln’s in the kitchen washing dishes—and General Grant’s upstairs making the beds.”

“Ah-h-h!” grunted Captain Pilgrim.

“Say, Wash, I sure would like to be in Washington tonight when Jeff Davis rides in. That Yankee rebellion didn’t last long, did it?”

Josie suddenly believed it and her world was crashing around her. The Boys in Blue, the Union forever—Mine eyes have seen the Glory of the Coming of the Lord. Her eyes filled with hot tears.

“You can’t take my brother prisoner—he’s not really an officer, he’s a doctor. He was wounded at Cold Harbor—”

“Doctor, eh? Don’t know anything about teeth, does he?” asked Tib, dismounting at the porch.

“Oh yes—that’s his specialty.”

“So you’re a tooth doctor? That’s what we been looking for all over Maryland-My-Maryland. If you’ll be so kind as to come in here you can pull a tooth of a real Bonaparte, a cousin of Emperor Napoleon III.

No joke—he’s attached to General Early’s staff. He’s been bawling his head off for an hour but the medical men went on with the ambulances.”

An officer came out on the porch, gave a nervous ear to a crackling of rifles in the distance, and bent an eye upon the buggy.

“We found a tooth specialist, Lieutenant,” said Tib. “Providence sent him into our lines and if Napoleon is still—”

“Thank God!” the officer exclaimed. “Bring him in. We didn’t know whether to take the Prince along or leave him.”

Suddenly a glimpse of the Confederacy was staged for Josie on the vine- covered veranda. There was a sudden egress: a spidery man in a shabby riding coat with faded stars, followed by two younger men cramming papers into a canvas sack.

Then a miscellany of officers, one on a single crutch, one stripped to an undershirt with the gold star of a general pinned to a bandage on his shoulder.

The general air was of nervous gaiety but Josie saw the reflection of disappointment in their tired eyes. Perceiving her, they made a single gesture: their dozen right hands rose to their dozen hats and they bowed in her direction.

Josie bowed back stiffly, trying unsuccessfully to bring hauteur and pious reproach into her face. In a moment they swung into their saddles.

General Early looked for a moment at the city that he could not conquer, a city that another Virginian had conceived arbitrarily out of a swamp eighty years before.

“No change in orders,” he said to the aide at his stirrup. “Tell Mosby that I want couriers every half hour up to Harper’s Ferry.”

“Yes, sir.”

The aide spoke to him in a low voice and his sun-strained eyes focused on Dr. Pilgrim in the buggy.

“I understand you’re a dentist,” he said. “Prince Napoleon has been with us as an observer. Pull out his tooth or whatever he needs.

These two troopers will stay with you. Do well by him and they’ll let you go without parole when you’ve finished.”

There was the clop and crunch of mounted men moving down a lane, and in a minute the last sally of the Army of Northern Virginia faded swiftly into the distance.

“We got a dentist here for Prince Napoleon,” said Tib to a French aide-de- camp who came out of the farmhouse.

“That’s excellent news.” He led the way inside. “The Prince is in such agony.”

“The doctor is a Yankee,” Tib continued. “One of us will have to stay while he’s operating.”

The stout invalid across the room, a gross miniature of his world-shaking uncle, tore his hand from a groaning mouth and sat upright in an armchair.

“Operating!” he cried. “My God! Is he going to operate?”

Dr. Pilgrim looked suspiciously at Tib.

“My sister—where will she be?”

“I’ve put her into the parlor, Doctor. Wash, you stay here.”

“I’ll need hot water,” said Dr. Pilgrim, “and my instrument case from the buggy.”

Prince Napoleon groaned again.

“Will you cut my head off of my neck? Ah, cette vie barbare!”

Tib consoled him politely.

“This doctor is a demon for teeth, Prince Napoleon.”

“I am a trained surgeon,” said Dr. Pilgrim stiffly. “Now, sir, will you take off that hat?”

The Prince removed the wide white Cordoba which topped a miscellaneous costume of red tail-coat, French uniform breeches and dragoon boots.

“Can we trust this medicine if he is a Yankee? How can I know he will not cut to kill? Does he know I am a French citizen?”

“Prince, if he doesn’t do well by you we got some apple trees outside and plenty rope.”

Tib went into the parlor where Miss Josie sat on the edge of a horsehair sofa.

“What are you going to do to my brother?”

Sorry for her lovely, anxious face, Tib said: “I’m more worried what he’s about to do to the Prince.”

An anguished howl arose from the library.

“You hear that?” Tib said. “The Prince is the one to worry about.”

“Are you going to send us to that Libby Prison?”

“Most certainly not, Madame. You’re going to be here till your brother fixes up the Prince; then as soon as our cavalry pickets come past you can continue your journey.”

Josie relaxed.

“I thought all the fighting was down in Virginia.”

“It is. That’s where we’re heading, I reckon—this is the third time I’ve ridden into Maryland with the army and it’s the third time I’m heading back with it.”

She looked at him for the first time with a certain human interest.

“What did my brother mean when he said you were