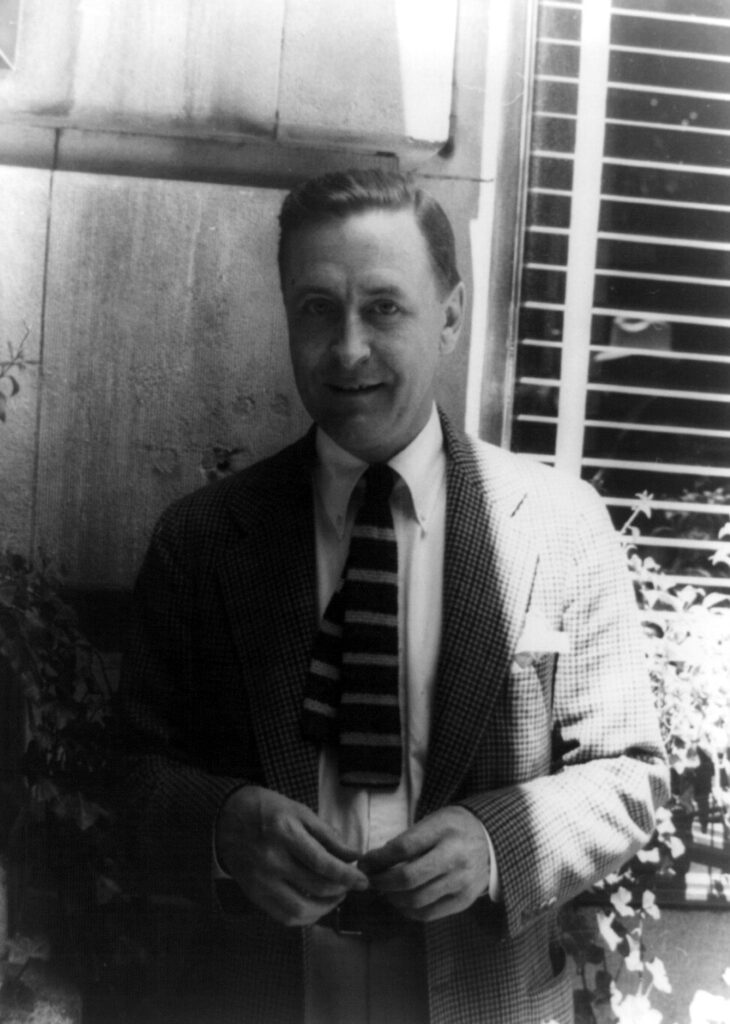

Design in Plaster, F. Scott Fitzgerald

“How long does the doctor think now?” Mary asked. With his good arm Martin threw back the top of the sheet, disclosing that the plaster armor had been cut away in front in the form of a square, so that his abdomen and the lower part of his diaphragm bulged a little from the aperture.

His dislocated arm was still high over his head in an involuntary salute.

“This was a great advance,” he told her. “But it took the heat wave to make Ottinger put in this window. I can’t say much for the view but—have you seen the wire collection?”

“Yes, I’ve seen it,” his wife answered, trying to look amused.

It was laid out on the bureau like a set of surgeons’ tools—wires bent to every length and shape so that the nurse could reach any point inside the plaster cast when perspiration made the itching unbearable.

Martin was ashamed at repeating himself.

“I apologize,” he said. “After two months you get medical psychology. All this stuff is fascinating to me. In fact—” he added, and with only faint irony, “—it is in a way of becoming my life.”

Mary came over and sat beside the bed raising him, cast and all, into her slender arms. He was chief electrical engineer at the studio and his thirty-foot fall wasn’t costing a penny in doctor’s bills.

But that—and the fact that the catastrophe had swung them together after a four months’ separation, was its only bright spot.

“I feel so close,” she whispered. “Even through this plaster.”

“Do you think that’s a nice way to talk?”

“Yes.”

“So do I.”

Presently she stood up and rearranged her bright hair in the mirror. He had seen her do it half a thousand times but suddenly there was a quality of remoteness about it that made him sad.

“What are you doing tonight?” he asked.

Mary turned, almost with surprise.

“It seems strange to have you ask me.”

“Why? You almost always tell me. You’re my contact with the world of glamour.”

“But you like to keep bargains. That was our arrangement when we began to live apart.”

“You’re being very technical.”

“No—but that WAS the arrangement. As a matter of fact I’m not doing anything. Bieman asked me to go to a preview, but he bores me. And that French crowd called up.”

“Which member of it?”

She came closer and looked at him.

“Why, I believe you’re jealous,” she said. “The wife of course. Or HE did, to be exact, but he was calling for his wife—she’d be there. I’ve never seen you like this before.”

Martin was wise enough to wink as if it meant nothing and let it die away, but Mary said an unfortunate last word.

“I thought you liked me to go with them.”

“That’s it,” Martin tried to go slow, “—with ’them,’ but now it’s ’he.’”

“They’re all leaving Monday,” she said almost impatiently. “I’ll probably never see him again.”

Silence for a minute. Since his accident there were not an unlimited number of things to talk about, except when there was love between them. Or even pity—he was accepting even pity in the past fortnight. Especially their uncertain plans about the future were in need of being preceded by a mood of love.

“I’m going to get up for a minute,” he said suddenly. “No, don’t help me—don’t call the nurse. I’ve got it figured out.”

The cast extended half way to his knee on one side but with a snake-like motion he managed to get to the side of the bed—then rise with a gigantic heave.

He tied on a dressing gown, still without assistance, and went to the window. Young people were splashing and calling in the outdoor pool of the hotel.

“I’ll go along,” said Mary. “Can I bring you anything tomorrow? Or tonight if you feel lonely?”

“Not tonight. You know I’m always cross at night—and I don’t like you making that long drive twice a day. Go along—be happy.”

“Shall I ring for the nurse?”

“I’ll ring presently.”

He didn’t though—he just stood. He knew that Mary was wearing out, that this resurgence of her love was wearing out. His accident was a very temporary dam of a stream that had begun to overflow months before.

When the pains began at six with their customary regularity the nurse gave him something with codein in it, shook him a cocktail and ordered dinner, one of those dinners it was a struggle to digest since he had been sealed up in his individual bomb-shelter.

Then she was off duty four hours and he was alone. Alone with Mary and the Frenchman.

He didn’t know the Frenchman except by name but Mary had said once:

“Joris is rather like you—only naturally not formed—rather immature.”

Since she said that, the company of Mary and Joris had grown increasingly unattractive in the long hours between seven and eleven.

He had talked with them, driven around with them, gone to pictures and parties with them—sometimes with the half comforting ghost of Joris’ wife along.

He had been near as they made love and even that was endurable as long as he could seem to hear and see them. It was when they became hushed and secret that his stomach winced inside the plaster cast.

That was when he had pictures of the Frenchman going toward Mary and Mary waiting. Because he was not sure just how Joris felt about her or about the whole situation.

“I told him I loved you,” Mary said—and he believed her, “I told him that I could never love anyone but you.”

Still he could not be sure how Mary felt as she waited in her apartment for Joris.

He could not tell if, when she said good night at her door, she turned away relieved, or whether she walked around her living room a little and later, reading her book, dropped it in her lap and looked up at the ceiling.

Or whether her phone rang once more for one more good night.

Martin hadn’t worried about any of these things in the first two months of their separation when he had been on his feet and well.

At half-past eight he took up the phone and called her; the line was busy and still busy at a quarter of nine.

At nine it was out of order; at nine-fifteen it didn’t answer and at a little before nine-thirty it was busy again. Martin got up, slowly drew on his trousers and with the help of a bellboy put on a shirt and coat.

“Don’t you want me to come, Mr. Harris?” asked the bellboy.

“No thanks. Tell the taxi I’ll be right down.”

When the boy had gone he tripped on the slightly raised floor of the bathroom, swung about on one arm and cut his head against the wash bowl.

It was not so much, but he did a clumsy repair job with the adhesive and, feeling ridiculous at his image in the mirror, sat down and called Mary’s number a last time—for no answer.

Then he went out, not because he wanted to go to Mary’s but because he had to go somewhere toward the flame, and he didn’t know any other place to go.

At ten-thirty Mary, in her nightgown, was at the phone.

“Thanks for calling. But, Joris, if you want to know the truth I have a splitting headache. I’m turning in.”

“Mary, listen,” Joris insisted. “It happens Marianne has a headache too and has turned in. This is the last night I’ll have a chance to see you alone. Besides, you told me you’d NEVER had a headache.”

Mary laughed.

“That’s true—but I AM tired.”

“I would promise to stay one-half hour—word of honor. I am only just around the corner.”

“No,” she said and a faint touch of annoyance gave firmness to the word. “Tomorrow I’ll have either lunch or dinner if you like, but now I’m going to bed.”

She stopped. She had heard a sound, a weight crunching against the outer door of her apartment. Then three odd, short bell rings.

“There’s someone—call me in the morning,” she said. Hurriedly hanging up the phone she got into a dressing gown.

By the door of her apartment she asked cautiously.

“Who’s there?”

No answer—only a heavier sound—a human slipping to the floor.

“Who is it?”

She drew back and away from a frightening moan.

There was a little shutter high in the door, like the peephole of a speakeasy, and feeling sure from the sound that whoever it was, wounded or drunk, was on the floor Mary reached up and peeped out.

She could see only a hand covered with freshly ripening blood, and shut the trap hurriedly. After a shaken moment, she peered once more.

This time she recognized something—afterwards she could not have said what—a way the arm lay, a corner of the plaster cast—but it was enough to make her open the door quickly and duck down to Martin’s side.

“Get doctor,” he whispered. “Fell on the steps and broke.”

His eyes closed as she ran for the phone.

Doctor and ambulance came at the same time. What Martin had done was simple enough, a little triumph of misfortune.

On the first flight of stairs that he had gone up for eight weeks, he had stumbled, tried to save himself with the arm that was no good for anything, then spun down catching and ripping on the stair rail.

After that a five minute drag up to her door.

Mary wanted to exclaim, “Why? Why?” but there was no one to hear. He came awake as the stretcher was put under him to carry him to the hospital, repair the new breakage with a new cast, start it over again.

Seeing Mary he called quickly.