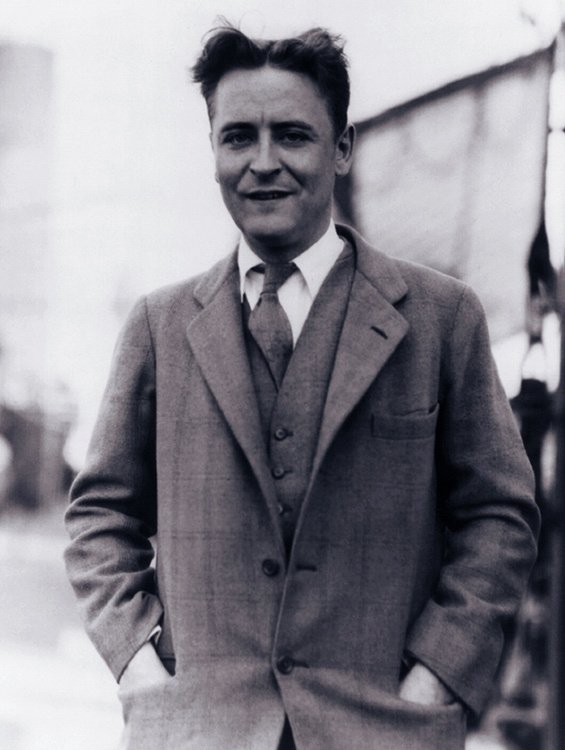

Last Kiss, F. Scott Fitzgerald

I

The sound of revelry fell sweet upon James Leonard’s ear. He alighted, a little awed by his new limousine, and walked down the red carpet through the crowd.

Faces strained forward, weird in the split glare of the drum lights—but after a moment they lost interest in him. Once Jim had been annoyed by his anonymity in Hollywood. Now he was pleased with it.

Elsie Donohue, a tall, lovely, gangling girl had a seat reserved for him at her table. “If I had no chance before,” she said, “what chance have I got now that you’re so important?” She was half teasing—but only half.

“You’re a stubborn man,” she said. “When we first met, you put me in the undesirable class. Why?” She tossed her shoulders despairingly as Jim’s eyes lingered on a little Chinese beauty at the next table.

“You’re looking at Ching Loo Poo-poo, Ching Loo Poo-poo! And for five long years I’ve come out to this ghastly town—”

“They couldn’t keep you away,” Jim objected. “It’s on your swing around—the Stork Club, Palm Beach and Dave Chasen’s.”

Tonight something in him wanted to be quiet. Jim was thirty-five and suddenly on the winning side of all this. He was one of those who said how pictures should go, what they should say. It was a fine pure feeling to be on top.

One was very sure that everything was for the best, that the lights shone upon fair ladies and brave men, that pianos dripped the right notes and that the young lips singing them spoke for happy hearts.

They absolutely must be happy, these beautiful faces. Andthen in a twilight rumba, a face passed Jim’s table that was not quite happy. It had gone before Jim formulated this opinion, yet it remained fixed on his memory for some seconds.

It was the head of a girl almost as tall as he was, with opaque brown eyes and cheeks as porcelain as those of the little Chinese.

“At least you’re back with the white race,” said Elsie, following his eyes.

Jim wanted to answer sharply: You’ve had your day—three husbands. How about me? Thirty-five and still trying to match every woman with a childhood love who died, still finding fatally in every girl the similarities and not the differences.

The next time the lights were dim he wandered through the tables to the entrance hall. Here and there friends hailed him—more than the usual number of course, because his rise had been in the Reporter that morning, but Jim had made other steps up and he was used to that.

It was a charity ball, and by the stairs was the man who imitated wallpaper about to go in and do a number and Bob Bordley with a sandwich board on his back:

At Ten Tonight in the Hollywood Bowl Sonja Henie Will Skate on Hot Soup.

By the bar Jim saw the producer whom he was displacing tomorrow having an unsuspecting drink with the agent who had contrived his ruin. Next to the agent was the girl whose face had seemed sad as she danced by in the rumba.

“Oh, Jim,” said the agent, “Pamela Knighton—your future star.”

She turned to him with professional eagerness. What the agent’s voice had said to her was: “Look alive! This is somebody.”

“Pamela’s joined my stable,” said the agent. “I want her to change her name to Boots.”

“I thought you said Toots,” the girl laughed.

“Toots or Boots. It’s the oo-oo sounds. Cutie shoots Toots. Judge Hoots. No conviction possible. Pamela is English. Her real name is Sybil Higgins.”

II

It seemed to Jim that the deposed producer was looking at him with an infinite something in his eyes—not hatred, not jealousy, but a profound and curious astonishment that asked: Why? Why?

For Heaven’s sake, why? More disturbed by this than enmity, Jim surprised himself by asking the English girl to dance. As they faced each other on the floor his exultation of the early evening came back.

“Hollywood’s a good place,” he said, as if to forestall any criticism from her. “You’ll like it. Most English girls do—they don’t expect too much. I’ve had luck working with English girls.”

“Are you a director?”

“I’ve been everything—from press agent on. I’ve just signed a producer’s contract that begins tomorrow.”

“I like it here,” she said after a minute. “You can’t help expecting things. But if they don’t come I could always teach school again.”

Jim leaned back and looked at her—his impression was of pink-and-silver frost. She was so far from a schoolmarm, even a schoolmarm in a Western, that he laughed. But again he saw that there was something sad and a little lost within the triangle formed by lips and eyes.

“Whom are you with tonight?” he asked.

“Joe Becker,” she answered, naming the agent. “Myself and three other girls.”

“Look—I have to go out for half an hour. To see a man—this is not phony. Believe me. Will you come along for company and night air?”

She nodded.

On the way they passed Elsie Donohue, who looked inscrutably at the girl and shook her head slightly at Jim. Out in the clear California night he liked his big car for the first time, liked it better than driving himself. The streets through which they rolled were quiet at this hour. Miss Knighton waited for him to speak.

“What did you teach in school?” he asked.

“Sums. Two and two are four and all that.”

“It’s a long jump from that to Hollywood.”

“It’s a long story.”

“It can’t be very long—you’re about eighteen.”

“Twenty.” Anxiously she asked, “Do you think that’s too old?”

“Lord, no! It’s a beautiful age. I know—I’m twenty-one myself and the arteries haven’t hardened much.”

She looked at him gravely, estimating his age and keeping it to herself.

“I want to hear the long story,” he said.

She sighed. “Well, a lot of old men fell in love with me. Old, old men—I was an old man’s darling.”

“You mean old gaffers of twenty-two?”

“They were between sixty and seventy. This is all true. So I became a gold digger and dug enough money out of them to go to New York. I walked into “21” the first day and Joe Becker saw me.”

“Then you’ve never been in pictures?” he asked.

“Oh, yes—I had a test this morning,” she told him.

Jim smiled. “And you don’t feel bad taking money from all those old men?” he inquired.

“Not really,” she said, matter-of-fact. “They enjoyed giving it to me. Anyhow it wasn’t really money. When they wanted to give me presents I’d send them to a certain jeweler, and afterward I’d take the presents back to the jeweler and get four-fifths of the cash.”

“Why, you little chiseler!”

“Yes,” she admitted. “Somebody told me how. I’m out for all I can get.”

“Didn’t they mind—the old men, I mean—when you didn’t wear their presents?”

“Oh, I’d wear them—once. Old men don’t see very well, or remember. But that’s why I haven’t any jewelry of my own.” She broke off. “This I’m wearing is rented.”

Jim looked at her again and then laughed aloud. “I wouldn’t worry about it. California’s full of old men.”

They had twisted into a residential district. As they turned a corner Jim picked up the speaking tube. “Stop here.” He turned to Pamela, “I have some dirty work to do.”

He looked at his watch, got out and went up the street to a building with the names of several doctors on a sign.

He went past the building walking slowly, and presently a man came out of the building and followed him. In the darkness between two lamps Jim went close, handed him an envelope and spoke concisely. The man walked off in the opposite direction and Jim returned to the car.

“I’m having all the old men bumped off,” he explained. “There’re some things worse than death.”

“Oh, I’m not free now,” she assured him. “I’m engaged.”

“Oh.” After a minute he asked, “To an Englishman?”

“Well—naturally. Did you think—“ She stopped herself but too late.

“Are we that uninteresting?” he asked.

“Oh, no.” Her casual tone made it worse. And when she smiled, at the moment when a street light shone in and dressed her beauty up to a white radiance, it was more annoying still.

“Now you tell me something,” she asked. “Tell me the mystery.”

“Just money,” he answered almost absently. “That little Greek doctor keeps telling a certain lady that her appendix is bad—we need her in a picture. So we bought him off. It’s the last time I’ll ever do anyone else’s dirty work.”

She frowned. “Does she really need her appendix out?”

He shrugged. “Probably not. At least that rat wouldn’t know. He’s her brother-in-law and he wants the money.”

After a long time Pamela spoke judicially. “An Englishman wouldn’t do that.”

“Some would,” he said shortly, “—and some Americans wouldn’t.”

“An English gentleman wouldn’t,” she insisted.

“Aren’t you getting off on the wrong foot,” he suggested, “if you’re going to work here?”

“Oh, I like Americans all right—the civilized ones.”

From her look Jim took this to include him, but far from being appeased he had a sense of outrage. “You’re taking chances,” he said. “In fact, I don’t see how you dared come out with me. I might have had feathers under my hat.”

“You didn’t bring a hat,” she said placidly. “Besides, Joe Becker said to. There might be something in it for me.”

After all he was a producer and you didn’t reach eminence by losing your temper—except on purpose. “I’m sure there’s something in it for you,” he said, listening to a stealthily treacherous purr creep into his voice.

“Are you?” she demanded. “Do you think I’ll stand out at all—or am I just one of the thousands?”

“You stand out already,” he