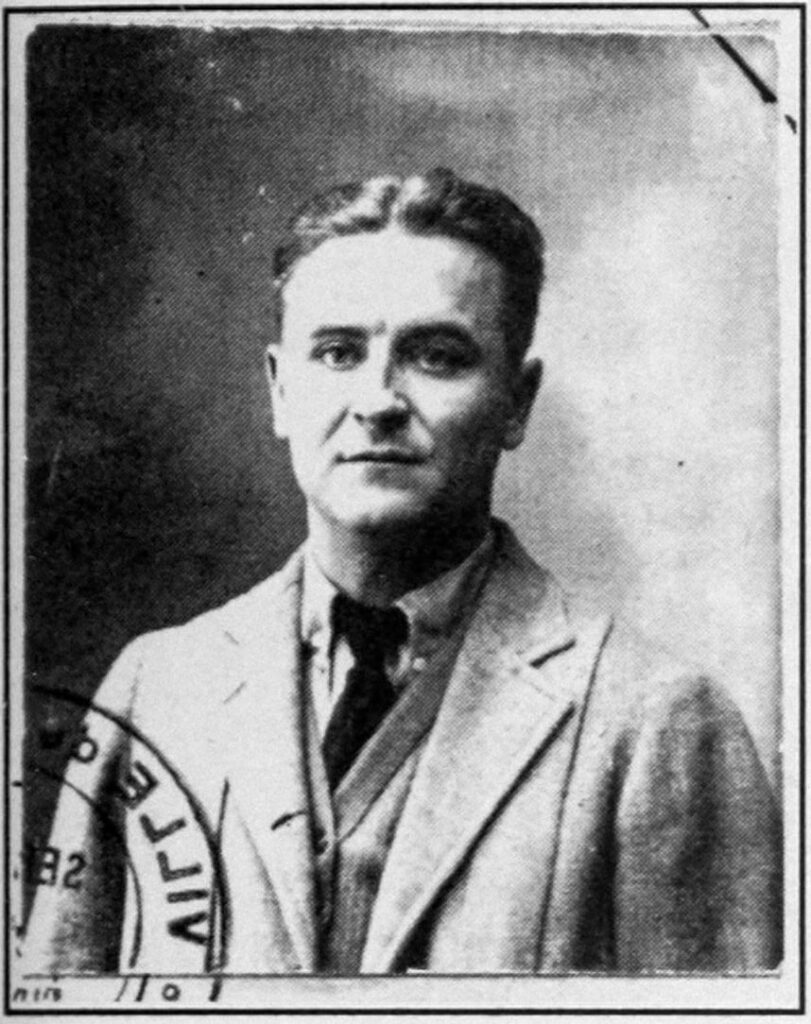

Lo, the Poor Peacock! F. Scott Fitzgerald

“Lo, the Poor Peacock!” was written in Baltimore early in 1935. After it was declined by The Saturday Evening Post and Ladies’ Home Journal, Harold Ober withdrew it.

In 1971 Esquire published this story in a version abridged and revised by one of the magazine’s editors. The text printed here is the story Fitzgerald wrote in 1935.

At this time, Fitzgerald was living at 1307 Park Avenue with Scottie, while Zelda was at Sheppard Pratt Hospital.

With his magazine earnings shrinking, money became a constant anxiety; and he was compelled to pawn the silver—a detail included in “Peacock” (the Supreme Court bowl had been a wedding present from the Associate Justices of the Alabama Supreme Court, on which Zelda’s father, Anthony Sayre, served for many years).

Fitzgerald’s Ledger entry for February 1935 reads: “Wrote story about Peacocks. Very sick. Debts terrible. Left for Tryon Sun 3rd. Oak Hall. Went on wagon for all liquor + alcohol on Thursday 7th (or Wed. 6th at 8.30 P.M)…”

Lo, the Poor Peacock!

I

Miss McCrary put the leather cover over the typewriter. Since it was the last time, Jason came over and helped her into her coat, rather to her embarrassment.

“Mr. Davis, remember if anything comes up that I didn’t cover on the memorandum, just you telephone. The letters are off; the files are straight. They’ll call for the typewriter on Monday.”

“You’ve been very nice.”

“Oh, don’t mention it. It’s been a pleasure. I’m only sorry—”

Jason murmured the current shibboleth: “If times pick up—”

A moment after her departure her face reappeared in the doorway.

“Give my love to the little girl. And I hope Mrs. Davis is better.”

At once it was lonely in the office. Not because of Miss McCrary’s physical absence—her presence often intruded on him—but because she was gone for good.

Putting on his coat Jason looked at the final memorandum—it contained nothing that need be done today—or in three days. It was nice to have a cleared desk, but he remembered days when business was so active, so pulsating that he telephoned instructions from railroad trains, radiographed from shipboard.

At home he found Jo and two other little girls playing Greta Garbo in the living room. Jo was so happy and ridiculous, so clownish with the childish smudge of rouge and mascara, that he decided to wait till after luncheon to introduce the tragedy.

Passing through the pantry he took a slant-eyed glance at the little girls still in masquerade, realizing that presently he would have to deflate one balloon of imagination.

The child who was playing Mae West—to the extent of saying ‘Come up and see me sometime’—admitted that she had never been permitted to see Mae West on the screen; she had been promised that privilege when she was fourteen.

Jason had been old enough for the war; he was thirty-eight. He wore a salt-and-pepper mustache; he was of middle height and well-made within the first ready-made suit he had ever owned.

Jo came close and demanded in quick French:

“Can I have these girls for lunch?”

“Pas aujourd ‘hui.”

“Bien.”

But she had to be told now. He didn’t want to give her bad news in the evening, when she was tired.

After luncheon when the maid had withdrawn, he said:

“I want to talk, now, about a serious matter.”

At the seriousness of his tone her eyes left a lingering crumb.

“It’s about school,” he said.

“About school?”

He plunged into his thesis.

“There’ve been hospital bills and not much business. I’ve figured out a budget—You know what that is: It’s how much you’ve got, placed against how much you can spend.

On clothes and food and education and so forth. Miss McCrary helped me figure it out before she left.”

“Has she left? Why?”

“Her mother’s been sick and she felt she ought to stay home and take care of her. And now, Jo, the thing that hits the budget hardest is school.”

Without quite comprehending what was coming, Jo’s face had begun to share the unhappiness of her father’s.

“It’s an expensive school with the extras and all—one of the most expensive day schools in the East.”

He struggled to his point, with the hurt that was coming to her germinating in his own throat.

“It doesn’t seem we can afford it any more this year.”

Still Jo did not quite understand, but there was a hush in the dining room.

“You mean I can’t go to school this term?” she asked, finally.

“Oh, you’ll go to school. But not Tunstall.”

“Then I don’t go to Tunstall Monday,” she said in a flat voice. “Where will I go?”

“You’ll take your second term at public school. They’re very good now. Mama never went to anything but a public school.”

“Daddy!” Her voice, comprehending at last, was shocked.

“We mustn’t make a mountain out of a mole-hill. After this year you can probably go back and finish at Tunstall—”

“But Daddy! Tunstall’s supposed to be the best. And you said this term you were satisfied with my marks—”

“That hasn’t anything to do with it. There are three of us, Jo, and we’ve got to consider all three. We’ve lost a great deal of money. There simply isn’t enough to send you.”

Two advance tears passed the frontier of her eyes, and navigated the cheeks.

Unable to endure her grief, he spoke on automatically:

“Which is best—spend too much and get into debt—or draw in our horns for a while?”

Still she wept silently. All the way to the hospital where they were paying their weekly visit she dripped involuntary tears.

Jason had undoubtedly spoiled her. For ten years the Davis household had lived lavishly in Paris; thence he had journeyed from Stockholm to Istamboul, placing American capital in many enterprises. It had been a magnificent enterprise—while it had lasted.

They inhabited a fine house on the Avenue Kleber, or else a villa at Beaulieu. There was an English Nanny, and then a governess, who imbued Jo with a sense of her father’s surpassing power.

She was brought up with the same expensive simplicity as the children she played with in the Champs Elysees.

Like them, she accepted the idea that luxury of life was simply a matter of growing up to it—the right to precedence, huge motors, speed boats, boxes at opera or ballet; Jo had early got into the habit of secretly giving away most of the surplus of presents with which she was inundated.

Two years ago the change began. Her mother’s health failed, and her father ceased to be any longer a mystery man, just back from Italy with a family of Lenci dolls for her.

But she was young and adjustable and fitted into the life at Tunstall school, not realizing how much she loved the old life. Jo tried honestly to love the new life too, because she loved things and people and she was prepared to like the still newer change.

But it took a little while because of the fact that she loved, that she was built to love, to love deeply and forever.

When they reached the hospital Jason said:

“Don’t tell mother about school. She might notice that it’s hit you rather hard, and make her unhappy. When you get—sort of used to it we’ll tell her.”

“I won’t say anything.”

They followed a tiled passage they both knew to an open door.

“Can we come in?”

“Can you?”

Together husband and daughter embraced her, almost jealously, from either side of the bed. With a deep quiet, their arms and necks strained together.

Annie Lee’s eyes filled with tears.

“Sit down. Have chairs, you all. Miss Carson, we need another chair.”

They had scarcely noticed the nurse’s presence.

“Now tell me everything. Have some chocolates. Aunt Vi sent them. She can’t remember what I can and can’t eat.”

Her face, ivory cold in winter, stung to a gentle wild rose in spring, then in summer pale as the white key of a piano, seldom changed. Only the doctors and Jason knew how ill she was.

“All’s well,” he said. “We keep the house going.”

“How about you, Jo? How’s school? Did you pass your exams?”

“Of course, Mama.”

“Good marks, much better than last year,” Jason added.

“How about the play?” Annie Lee pursued innocently. “Are you still going to be Titania?”

“I don’t know, Mama.”

Jason switched the subject to ‘the farm,’ a remnant of a once extensive property of Annie Lee’s.

“I’d sell it if we could. I can’t see how your mother ever made it pay.”

“She did though. Right up to the day of her death.”

“It was the sausage. And there doesn’t seem to be a market for it any more.”

The nurse warned them that time was up. As if to save the precious minutes Annie Lee thrust out a white hand to each.

As they got into the car, Jo asked:

“Daddy, what happened to our money?”

Well—better tell her than to have her brood about it.

“It’s complicated. The Europeans couldn’t pay interest on what we lent them. You know interest?”

“Of course. We had it in the Second Main.”

“My job was to judge whether a business showed promise, and if I thought so we loaned them money. When bad times came and they couldn’t pay, we wouldn’t loan any more. So my job was played out and we came home.”

He went on to say that the money he had invested in the venture—oh, many thousands, oh, never mind how much, Jo—and now all that money was ‘tied up.’

Under the aegis of the old shot tower they slowed by a garage to fill the tank.

“Why do you like to stop at this station, Daddy? Beside that ugly old chimney over there?”

“That’s not a chimney. Don’t you know what it is? During the Revolution they had to drop lead down to make the bullets