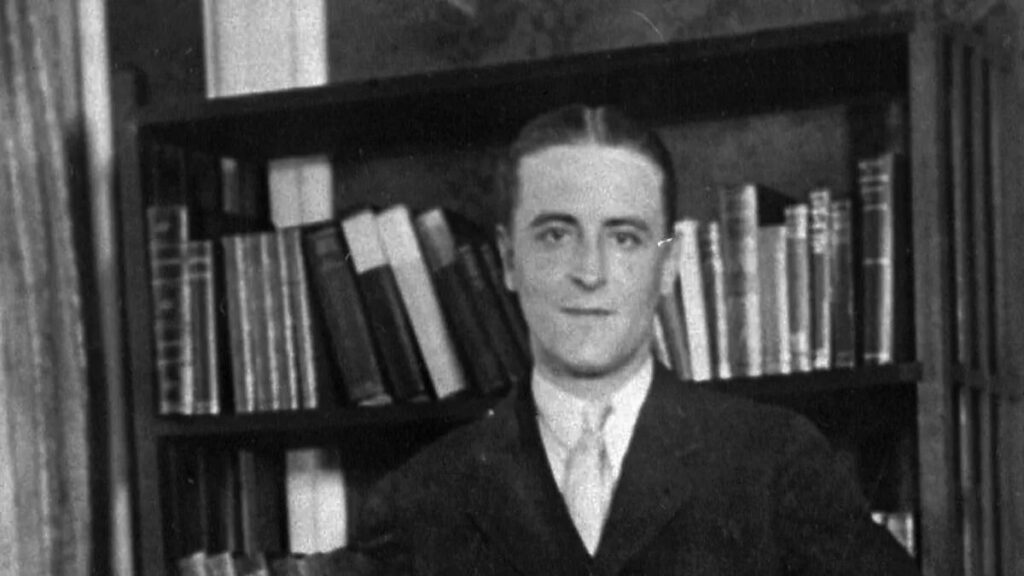

Mr. Icky, F. Scott Fitzgerald

This has the distinction of being the only magazine piece ever written in a New York hotel.

The business was done in a bedroom in the Knickerbocker, and shortly afterward that memorable hostelry closed its doors forever.

When a fitting period of mourning had elapsed it was published in the “Smart Set.”

Mr. IckyThe Quintessence of Quaintness in one act

The Scene is the Exterior of a Cottage in West Issacshire on a desperately Arcadian afternoon in August. Mr. Icky, quaintly dressed in the costume of an Elizabethan peasant, is pottering and doddering among the pots and dods.

He is an old man, well past the prime of life, no longer young. From the fact that there is a burr in his speech and that he has absent-mindedly put on his coat wrongside out, we surmise that he is either above or below the ordinary superficialities of life.

Near him on the grass lies Peter, a little boy. Peter, of course, has his chin on his palm like the pictures of the young Sir Walter Raleigh.

He has a complete set of features, including serious, sombre, even funereal, gray eyes—and radiates that alluring air of never having eaten food. This air can best be radiated during the afterglow of a beef dinner. He is looking at Mr. Icky, fascinated.

Silence. . . . The song of birds.

Peter: Often at night I sit at my window and regard the stars. Sometimes I think they’re my stars…. (Gravely) I think I shall be a star some day….

Mr. Icky: (Whimsically) Yes, yes … yes….

Peter: I know them all: Venus, Mars, Neptune, Gloria Swanson.

Mr. Icky: I don’t take no stock in astronomy…. I’ve been thinking o’ Lunnon, laddie. And calling to mind my daughter, who has gone for to be a typewriter…. (He sighs.)

Peter: I liked Ulsa, Mr. Icky; she was so plump, so round, so buxom.

Mr. Icky: Not worth the paper she was padded with, laddie. (He stumbles over a pile of pots and dods.)

Peter: How is your asthma, Mr. Icky?

Mr. Icky: Worse, thank God!…(Gloomily.) I’m a hundred years old… I’m getting brittle.

Peter: I suppose life has been pretty tame since you gave up petty arson.

Mr. Icky: Yes… yes…. You see, Peter, laddie, when I was fifty I reformed once—in prison.

Peter: You went wrong again?

Mr. Icky: Worse than that. The week before my term expired they insisted on transferring to me the glands of a healthy young prisoner they were executing.

Peter: And it renovated you?

Mr. Icky: Renovated me! It put the Old Nick back into me! This young criminal was evidently a suburban burglar and a kleptomaniac. What was a little playful arson in comparison!

Peter: (Awed) How ghastly! Science is the bunk.

Mr. Icky: (Sighing) I got him pretty well subdued now. ’Tisn’t every one who has to tire out two sets o’ glands in his lifetime. I wouldn’t take another set for all the animal spirits in an orphan asylum.

Peter: (Considering) I shouldn’t think you’d object to a nice quiet old clergyman’s set.

Mr. Icky: Clergymen haven’t got glands—they have souls.

(There is a low, sonorous honking off stage to indicate that a large motor-car has stopped in the immediate vicinity. Then a young man handsomely attired in a dress-suit and a patent-leather silk hat comes onto the stage. He is very mundane. His contrast to the spirituality of the other two is observable as far back as the first row of the balcony. This is Rodney Divine.)

Divine: I am looking for Ulsa Icky.

(Mr. Icky rises and stands tremulously between two dods.)

Mr. Icky: My daughter is in Lunnon.

Divine: She has left London. She is coming here. I have followed her.

(He reaches into the little mother-of-pearl satchel that hangs at his side for cigarettes. He selects one and scratching a match touches it to the cigarette. The cigarette instantly lights.)

Divine: I shall wait.

(He waits. Several hours pass. There is no sound except an occasional cackle or hiss from the dods as they quarrel among themselves. Several songs can be introduced here or some card tricks by Divine or a tumbling act, as desired.)

Divine: It’s very quiet here.

Mr. Icky: Yes, very quiet….

(Suddenly a loudly dressed girl appears; she is very worldly. It is Ulsa Icky. On her is one of those shapeless faces peculiar to early Italian painting.)

Ulsa: (In a coarse, worldly voice) Feyther! Here I am! Ulsa did what?

Mr. Icky: (Tremulously) Ulsa, little Ulsa. (They embrace each other’s torsos.)

Mr. Icky: (Hopefully) You’ve come back to help with the ploughing.

Ulsa: (Sullenly) No, feyther; ploughing’s such a beyther. I’d reyther not.

(Though her accent is broad, the content of her speech is sweet and clean.)

Divine: (Conciliatingly) See here, Ulsa. Let’s come to an understanding.

(He advances toward her with the graceful, even stride that made him captain of the striding team at Cambridge.)

Ulsa: You still say it would be Jack?

Mr. Icky: What does she mean?

Divine: (Kindly) My dear, of course, it would be Jack. It couldn’t be Frank.

Mr. Icky: Frank who?

Ulsa: It would be Frank!

(Some risqué joke can be introduced here.)

Mr. Icky: (Whimsically) No good fighting…no good fighting…

Divine: (Reaching out to stroke her arm with the powerful movement that made him stroke of the crew at Oxford) You’d better marry me.

Ulsa: (Scornfully) Why, they wouldn’t let me in through the servants’ entrance of your house.

Divine: (Angrily) They wouldn’t! Never fear—you shall come in through the mistress’ entrance.

Ulsa: Sir!

Divine: (In confusion) I beg your pardon. You know what I mean?

Mr. Icky: (Aching with whimsey) You want to marry my little Ulsa?…

Divine: I do.

Mr. Icky: Your record is clean.

Divine: Excellent. I have the best constitution in the world—

Ulsa: And the worst by-laws.

Divine: At Eton I was a member at Pop; at Rugby I belonged to Near-beer. As a younger son I was destined for the police force—

Mr. Icky: Skip that…. Have you money?…

Divine: Wads of it. I should expect Ulsa to go down town in sections every morning—in two Rolls Royces. I have also a kiddy-car and a converted tank. I have seats at the opera—

Ulsa: (Sullenly) I can’t sleep except in a box. And I’ve heard that you were cashiered from your club.

Mr. Icky: A cashier? …

Divine: (Hanging his head) I was cashiered.

Ulsa: What for?

Divine: (Almost inaudibly) I hid the polo balls one day for a joke.

Mr. Icky: Is your mind in good shape?

Divine: (Gloomily) Fair. After all what is brilliance? Merely the tact to sow when no one is looking and reap when every one is.

Mr. Icky: Be careful. … I will not marry my daughter to an epigram….

Divine: (More gloomily) I assure you I’m a mere platitude. I often descend to the level of an innate idea.

Ulsa: (Dully) None of what you’re saying matters. I can’t marry a man who thinks it would be Jack. Why Frank would—

Divine: (Interrupting) Nonsense!

Ulsa: (Emphatically) You’re a fool!

Mr. Icky: Tut-tut! … One should not judge … Charity, my girl. What was it Nero said?—“With malice toward none, with charity toward all—”

Peter: That wasn’t Nero. That was John Drinkwater.

Mr. Icky: Come! Who is this Frank? Who is this Jack?

Divine: (Morosely) Gotch.

Ulsa: Dempsey.

Divine: We were arguing that if they were deadly enemies and locked in a room together which one would come out alive. Now I claimed that Jack Dempsey would take one—

Ulsa: (Angrily) Rot! He wouldn’t have a—

Divine: (Quickly) You win.

Ulsa: Then I love you again.

Mr. Icky: So I’m going to lose my little daughter…

Ulsa: You’ve still got a houseful of children.

(Charles, Ulsa’s brother, coming out of the cottage. He is dressed as if to go to sea; a coil of rope is slung about his shoulder and an anchor is hanging from his neck.)

Charles: (Not seeing them) I’m going to sea! I’m going to sea!

(His voice is triumphant.)

Mr. Icky: (Sadly) You went to seed long ago.

Charles: I’ve been reading “Conrad.”

Peter: (Dreamily) “Conrad,” ah! “Two Years Before the Mast,” by Henry James.

Charles: What?

Peter: Walter Pater’s version of “Robinson Crusoe.”

Charles: (To his feyther) I can’t stay here and rot with you. I want to live my life. I want to hunt eels.

Mr. Icky: I will be here… when you come back….

Charles: (Contemptuously) Why, the worms are licking their chops already when they hear your name.

(It will be noticed that some of the characters have not spoken for some time. It will improve the technique if they can be rendering a spirited saxophone number.)

Mr. Icky: (Mournfully) These vales, these hills, these McCormick harvesters—they mean nothing to my children. I understand.

Charles: (More gently) Then you’ll think of me kindly, feyther. To understand is to forgive.

Mr. Icky: No…no….We never forgive those we can understand….We can only forgive those who wound us for no reason at all….

Charles: (Impatiently) I’m so beastly sick of your human nature line. And, anyway, I hate the hours around here.

(Several dozen more of Mr. Icky’s children trip out of the house, trip over the grass, and trip over the pots and dods. They are muttering “We are going away,” and “We are leaving you.”)

Mr. Icky: (His heart breaking) They’re all deserting me. I’ve been too kind. Spare the rod and spoil the fun. Oh, for the glands of a Bismarck.

(There is a honking outside—probably Divine’s chauffeur growing impatient for his master.)

Mr. Icky: (In misery) They do not love the soil! They have been faithless to the Great Potato Tradition! (He picks up a handful of soil passionately and rubs it on his bald head. Hair sprouts.) Oh, Wordsworth, Wordsworth, how true you spoke!

“No motion has she now, no force;

She does not hear or feel;

Roll’d round on earth’s diurnal course

In some one’s Oldsmobile.”

(They all groan and shouting “Life”