On Your Own, F. Scott Fitzgerald

I

The third time he walked around the deck Evelyn stared at him. She stood leaning against the bulwark and when she heard his footsteps again she turned frankly and held his eyes for a moment until his turned away, as a woman can when she has the protection of other men’s company, Barlotto, playing ping-pong with Eddie O’Sullivan, noticed the encounter.

“Aha!” he said, before the stroller was out of hearing, and when the rally was finished: “Then you’re still interested even if it’s not the German Prince.”

“How do you know it’s not the German Prince?” Evelyn demanded.

“Because the German Prince is the horse-faced man with white eyes. This one”—he took a passenger list from his pocket—“is either Mr George Ives, Mr Jubal Early Robbins and valet, or Mr Joseph Widdle with Mrs Widdle and six children.”

It was a medium-sized German boat, five days westbound from Cherbourg. The month was February and the sea was dingy grey and swept with rain. Canvas sheltered all the open portions of the promenade deck, even the ping-pong table was wet.

K’tap K’tap K’tap K’tap. Barlotto looked like Valentino—since he got fresh in the rumba number she had disliked playing opposite him. But Eddie O’Sullivan had been one of her best friends in the company.

Subconsciously she was waiting for the solitary promenader to round the deck again but he didn’t. She faced about and looked at the sea through the glass windows; instantly her throat closed and she held herself dose to the wooden rail to keep her shoulders from shaking.

Her thoughts rang aloud in her ears: “My father is dead—when I was little we would walk to town on Sunday morning, I in my starched dress, and he would buy the Washington paper and a cigar and he was so proud of his pretty little girl.

He was always so proud of me—he came to New York to see me when I opened with the Marx Brothers and he told everybody in the hotel he was my father, even the elevator boys. I’m glad he did, it was so much pleasure for him, perhaps the best time he ever had since he was young. He would like it if he knew I was coming all the way from London.”

“Game and set,” said Eddie.

She turned around. “We’ll go down and wake up the Barneys and have some bridge, eh?” suggested Barlotto.

Evelyn led the way, pirouetting once and again on the moist deck, then breaking into an “Off to Buffalo” against a sudden breath of wet wind.

At the door she slipped and fell inward down the stair, saved herself by a perilous one-arm swing—and was brought up against the solitary promenader.

Her mouth fell open comically—she balanced for a moment Then the man said, “I beg your pardon,” in an unmistakably southern voice. She met his eyes again as the three of them passed on. The man picked up Eddie O’Sullivan in the smoking room the next afternoon.

“Aren’t you the London cast of Chronic Affection?”

“We were until three days ago. We were going to run another two weeks but Miss Lovejoy was called to America so we closed.”

“The whole cast on board?” The man’s curiosity was inoffensive, it was a really friendly interest combined with a polite deference to the romance of the theatre. Eddie O’Sullivan liked him.

“Sure, sit down. No, there’s only Barlotto, the juvenile, and Miss Lovejoy and Charles Barney, the producer, and his wife. We left in twenty-four hours—the others are coming on the Homeric.”

“I certainly did enjoy seeing your show. I’ve been on a trip around the world and I turned up in London two weeks ago just ready for something American—and you had it.”

An hour later Evelyn poked her head around the corner of the smoking-room door and found them there.

“Why are you hiding out on us?” she demanded. “Who’s going to laugh at my stuff? That bunch of card sharps down there?”

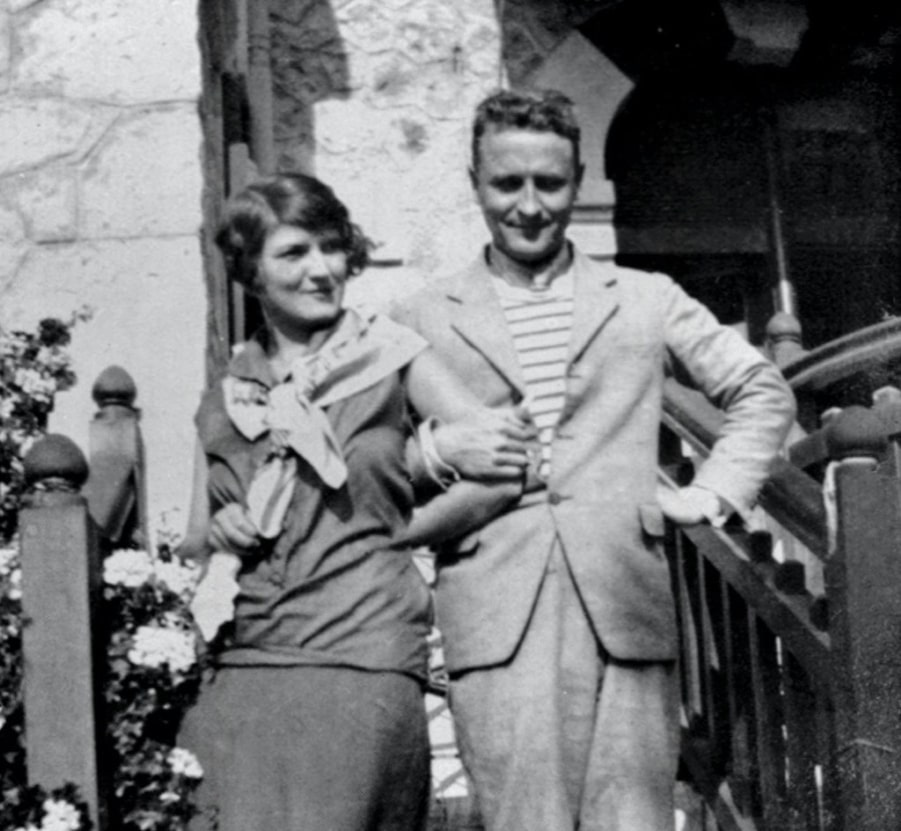

Eddie introduced Mr George Ives. Evelyn saw a handsome, well-built man of thirty with a firm and restless face. At the corners of his eyes two pairs of fine wrinkles indicated an effort to meet the world on some other basis than its own.

On his pan George Ives saw a rather small dark-haired girl of twenty-six, burning with a vitality that could only be described as “professional”. Which is to say it was not amateur—it could never use itself up upon any one person or group.

At moments it possessed her so entirely, turning every shade of expression, every casual gesture, into a thing of such moment that she seemed to have no real self of her own. Her mouth was made of two small intersecting cherries pointing off into a bright smile; she had enormous, dark brown eyes.

She was not beautiful but it took her only about ten seconds to persuade people that she was. Her body was lovely with little concealed muscles of iron. She was in black now and overdressed—she was always very chic and a little overdressed.

“I’ve been admiring you ever since you hurled yourself at me yesterday afternoon,” he said.

“I had to make you some way or other, didn’t I? What’s a girl going to with herself on a boat—fish?” They sat down.

“Have you been in England long?” George asked. “About five years—I go bigger over there.” In its serious moments her voice had the ghost of a British accent. “I’m not really very good at anything—I sing a little, dance a little, down a little, so the English think they’re getting a bargain. In New York they want specialists.”

It was apparent that she would have preferred an equivalent popularity in New York.

Barney, Mrs Barney and Barlotto came into the bar. “Aha!” Barlotto cried when George Ives was introduced. “She won’t believe he’s not the Prince.” He put his hand on George’s knee. “Miss Lovejoy was looking for the Prince the first day when she heard he was on board. We told her it was you.”

Evelyn was weary of Barlotto, weary of all of them, except Eddie O’Sullivan, though she was too tactful to have shown it when they were working together. She looked around. Save for two Russian priests playing chess their party was alone in the smoking-room—there were only thirty first-class passengers, with accommodations for two hundred.

Again she wondered what sort of an America she was going back to. Suddenly the room depressed her—it was too big, too empty to fill and she felt the necessity of creating some responsive joy and gaiety around her.

“Let’s go down to my salon,” she suggested, pouring all her enthusiasm into her voice, making them a free and thrilling promise. “We’ll play the phonograph and send for the handsome doctor and the chief engineer and get them in a game of stud. I’ll be the decoy.”

As they went downstairs she knew she was doing this for the new man.

She wanted to play to him, show him what a good time she could give people. With the phonograph wailing “You’re driving me crazy” she began building up a legend. She was a “gun moll” and the whole trip had been a I frame to get Mr Ives into the hands of the mob.

Her throaty mimicry flicked here and there from one to the other; two ship’s officers coming in were caught up in it and without knowing much English still understood the verve and magic of the impromptu performance.

She was Anne Pennington, Helen Morgan, the effeminate waiter who came in for an order, she was everyone there in turn, and all in pace with the ceaseless music.

Later George Ives invited them all to dine with him in the upstairs restaurant that night. And as the party broke up and Evelyn’s eyes sought his approval he asked her to walk with him before dinner.

The deck was still damp, still canvassed in against the persistent of rain. The lights were a dim and murky yellow and blankets tumbled awry on empty deck chairs.

“You were a treat,” he said. “You’re like—Mickey Mouse.”

She took his arm and bent double over it with laughter.

“I like being Mickey Mouse. Look—there’s where I stood and stared you every time you walked around. Why didn’t you come around the fourth time?”

“I was embarrassed so I went up to the boat deck.”

As they turned at the bow there was a great opening of doors and a flooding out of people who rushed to the rail.

“They must have had a poor supper,” Evelyn said. “No—look!”

It was the Europa—a moving island of light. It grew larger minute by minute, swelled into a harmonious fairyland with music from its deck and searchlights playing on its own length.

Through field-glasses they could discern figures lining the rail and Evelyn spun out the personal history of a man who was pressing his own pants in a cabin. Charmed they watched its sure matchless speed.

“Oh, Daddy, buy me that!” Evelyn cried, and then something suddenly broke inside her—the sight of beauty, the reaction to her late excitement choked her up and she thought vividly of her father. Without a word she went inside.

Two days later she stood with George Ives on the deck while the gaunt scaffolding of Coney Island slid by.

“What was Barlotto saying to you just now?” she demanded.

George laughed.

“He was saying just about what Barney said this afternoon, only he was more excited about it.”

She groaned.

“He said that you played with everybody—and that I was foolish if I thought this little boat flirtation meant anything—everybody had been through being in love