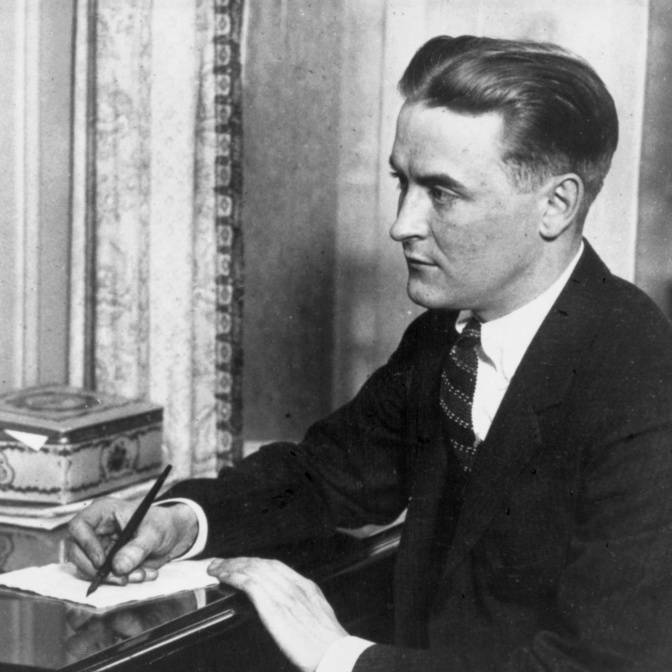

The Vegetable, or From President to Postman, F. Scott Fitzgerald

“Any man who doesn’t want to get on in the

world, to make a million dollars, and maybe even

park his toothbrush in White House, hasn’t

got as much to him as a good dog has—he’s

nothing more or less than a vegetable.”

—From a Current Magazine.

TO KATHERINE TIGHE and EDMUND WILSON, Jr.

WHO DELETED MANY ABSURDITIES

FROM MY FIRST TWO NOVELS I RECOMMEND

THE ABSURDITIES SET DOWN HERE

ACT I

ACT II

ACT III

THE VEGETABLE

ACT I

This is the “living” room of Jerry Frost’s house. It is evening. The room (and, by implication, the house) is small and stuffy—it’s an awful bother to raise these old-fashioned windows; some of them stick, and besides it’s extravagant to let in much cold air, here in the middle of March. I can’t say much for the furniture, either.

Some of it’s instalment stuff, imitation leather with the grain painted on as an after-effect, and some of it’s dingily, depressingly old.

That bookcase held “Ben Hur” when it was a best-seller, and it’s now trying to digest “A Library of the World’s Best Literature” and the “Wit and Humor of the United States in Six Volumes.” That couch would be dangerous to sit upon without a map showing the location of all craters, hillocks, and thistle-patches. And three dead but shamefully unburied clocks stare eyelessly before them from their perches around the walls.

Those walls—God! The history of American photography hangs upon them. Photographs of children with{4} puffed dresses and depressing leers, taken in the Fauntleroy nineties, of babies with toothless mouths and idiotic eyes, of young men with the hair cuts of ’85 and ’90 and ’02, and with neckties that loop, hoist, snag, or flare in conformity to some esoteric, antiquated standard of middle-class dandyism.

And the girls! You’d have to laugh at the girls! Imitation Gibson girls, mostly; you can trace their histories around the room, as each of them withered and stated. Here’s one in the look-at-her-little-toes-aren’t-they-darling period, and here she is later when she was a little bother of ten. Look! This is the way she was when she was after a husband.

She might be worse. There’s a certain young charm or something, but in the next picture you can see what five years of general housework have done to her. You wouldn’t turn your eyes half a degree to watch her in the street. And that was taken six years ago—now she’s thirty and already an old woman.

You’ve guessed it. That last one, allowing for the photographer’s kind erasure of a few lines, is Mrs. Jerry Frost. If you listen for a minute, you’ll hear her, too.

But wait. Against my will, I’ll have to tell you a few sordid details about the room. There’s got to be a door in plain sight that leads directly outdoors, and then there are two other doors, one to the dining-room and one{5} to the second floor—you can see the beginning of the stairs. Then there’s a window somewhere that’s used in the last act. I hate to mention these things, but they’re part of the plot.

Now you see when the curtain went up, Jerry Frost had left the little Victrola playing and wandered off to the cellar or somewhere, and Mrs. Jerry (you can call her Charlotte) hears it from where she is up-stairs. Listen!

“Some little bug is going to find you, so-o-ome day!”

That’s her. She hasn’t got much of a voice, has she? And she will sing one key higher than the Victrola. And now the darn Victrola’s running down and giving off a ghastly minor discord like the death agony of a human being.

Charlotte. [She’s up-stairs, remember.] Jerry, wind up the graphophone.

There’s no answer.

Jer-ry!

Still no answer.

Jerry, wind up the graphophone. It isn’t good for it.

Yet again no answer.

All right— [smugly]—if you want to ruin it, I don’t care.{6}

The phonograph whines, groans, gags, and dies, and almost simultaneously with its last feeble gesture a man comes into the room, saying: “What?” He receives no answer. It is Jerry Frost, in whose home we are.

Jerry Frost is thirty-five. He is a clerk for the railroad at $3,000 a year. He possesses no eyebrows, but nevertheless he constantly tries to knit them. His lips are faintly pursed at all times, as though about to emit an enormous opinion upon some matter of great importance.

On the wall there is a photograph of him at twenty-seven—just before he married. Those were the days of his high yellow pompadour. That is gone now, faded like the rest of him into a docile pattern without grace or humor.

After his mysterious and unanswered “What?” Jerry stares at the carpet, surely not in æsthetic approval, and becomes engrossed in his lack of thoughts. Suddenly he gives a twitch and tries to reach with his hand some delicious sector of his back. He can almost reach it, but not quite—poor man!—so he goes to the mantelpiece and rubs his back gently, pleasingly, against it, meanwhile keeping his glance focussed darkly upon the carpet.{7}

He is finished. He is at physical ease again. He leans over the table—did I say there was a table?—and turns the pages of a magazine, yawning meanwhile and tentatively beginning a slow clog step with his feet.

Presently this distracts him from the magazine, and he looks apathetically at his feet. Then suddenly he sits in a chair and begins to sing, unmusically, and with faint interest, a piece which is possibly his own composition. The tune varies considerably, but the words have an indisputable consistency, as they are composed wholly of the phrase: “Everybody is there, everybody is there!”

He is a motion-picture of tremendous, unconscious boredom.

Suddenly he gives out a harsh, bark-like sound and raises his hand swiftly, as though he were addressing an audience. This fails to amuse him; the arm falters, strays lower——

Jerry. Char-lit! Have you got the Saturday Evening Post?

There is no reply.

Char-lit!

Still no reply.

Char-lit!{8}

Charlotte [with syrupy recrimination]. You didn’t bother to answer me, so I don’t think I should bother to answer you.

Jerry [indignant, incredulous]. Answer you what?

Charlotte. You know what I mean.

Jerry. I mos’ certainly do not.

Charlotte. I asked you to wind up the graphophone.

Jerry [glancing at it indignantly]. The phonograph?

Charlotte. Yes, the graphophone!

Jerry. It’s the first time I knew it. [He is utterly disgusted. He starts to speak several times, but each time he hesitates. Disgust settles upon his face, in a heavy pall. Then he remembers his original question.] Have you got the Saturday Evening Post?

Charlotte. Yes, I told you!

Jerry. You did not tell me!

Charlotte. I can’t help it if you’re deaf!

Jerry. Deaf? Who’s deaf? [After a pause.] No more deaf than you are. [After another pause.] Not half as much.

Charlotte. Don’t talk so loud—you’ll wake the people next door.

Jerry [incredulously]. The people next door!

Charlotte. You heard me!{9}

Jerry is beaten, and taking it very badly. He is beginning to brood when the telephone rings. He answers it.

Jerry. Hello!… [With recognition and rising interest.] Oh, hello…. Did you get the stuff…. Just one gallon is all I want…. No, I can’t use more than one gallon…. [He looks around thoughtfully.] Yes, I suppose so, but I’d rather have you mix it before you bring it…. Well, about nine o’clock, then. [He rings off, gleeful now, smiling. Then sudden worry, and the hairless eyebrows knit together.

He takes a note-book out of his pocket, lays it open before him, and picks up the receiver.] Midway 9191…. Yes…. Hello, is this Mr.—Mr. S-n-o-o-k-s’s residence?… Hello, is this Mr. S-n-o-o-k-s’s residence?… [Very distinctly.] Mr. Snukes or Snooks…. Mr. S-n-, the boo—the fella that gets stuff, hooch … h-o-o-c-h…. No, Snukes or Snooks is the man I want…. Oh.

Why, a fella down-town gave me your husband’s name and he called me up—at least, I called him up first, and then he called me up just now—see?… You see? Hello—is this—am I talking to the wife of the—of the—of the fella that gets stuff for you? The b-o-o-t-l-e-g-g-e-r? Oh, you know, the bootlegger. [He breathes hard after this word. Do you suppose Central will tell on him?] … Oh. Well, you see, I wanted to tell him when he comes to-night to come to the back door…. No, Hooch is{10} not my name. My name is Frost. 2127 Osceola Avenue…. Oh, he’s left already? Oh, all right. Thanks…. Well, good-by…. Well, good-by … good-by. [He rings off. Again his hairless brows are knit with worry.] Char-lit!

Charlotte [abstractedly]. Yes?

Jerry. Charlit, if you want to read a good story, read the one about the fella who gets shipwrecked on the Buzzard Islands and meets the Chinese girl, only she isn’t a Chinese girl at all.

Charlotte [she’s still up-stairs, remember]. What?

Jerry. There’s one story in there—are you reading the Saturday Evening Post?

Charlotte. I would be if you didn’t interrupt me every minute.

Jerry. I’m not. I just wanted to tell you there’s one story in there about a Chinese girl who gets wrecked on the Buzzard Islands that isn’t a Chinese——

Charlotte. Oh, let up, for heaven’s sakes! Don’t nag me.

Clin-n-ng! That’s the door-bell.

There’s the door-bell.

Jerry [with fine sarcasm]. Oh, really? Why, I thought it was a cow-bell.

Charlotte [witheringly]. Ha-ha!{11}

Well, he’s gone to the door. He opens it, mumbles something, closes it. Now he’s back.

Jerry. It wasn’t anybody.

Charlotte. It must have been.

Jerry. What?

Charlotte. It couldn’t have rung itself.

Jenny [in disgust]. Oh, gosh, you think that’s funny. [After a pause.] It was a man who wanted 2145. I told him this was 2127, so he went away.

Charlotte is now audibly descending a crickety flight of stairs, and here she is! She’s thirty, and old for