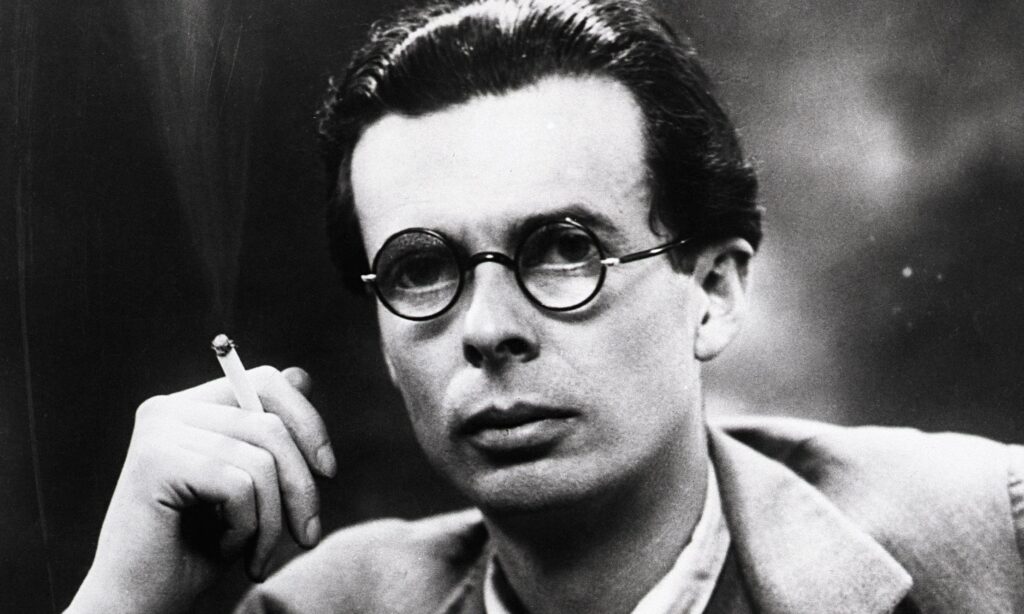

After the Fireworks, Aldous Leonard Huxley

After the Fireworks

1

‘Late as usual. Late.’ Judd’s voice was censorious. The words fell sharp, like beak-blows. ‘As though I were a nut,’ Miles Fanning thought resentfully, ‘and he were a woodpecker. And yet he’s devotion itself, he’d do anything for me. Which is why, I suppose, he feels entitled to crack my shell each time he sees me.’ And he came to the conclusion, as he had so often come before, that he really didn’t like Colin Judd at all. ‘My oldest friend, whom I quite definitely don’t like. Still . . .’ Still, Judd was an asset, Judd was worth it.

‘Here are your letters,’ the sharp voice continued.

Fanning groaned as he took them. ‘Can’t one ever escape from letters? Even here, in Rome? They seem to get through everything. Like filter-passing bacteria. Those blessed days before post offices!’ Sipping, he examined, over the rim of his coffee cup, the addresses on the envelopes.

‘You’d be the first to complain if people didn’t write,’ Judd rapped out. ‘Here’s your egg. Boiled for three minutes exactly. I saw to it myself.’

Taking his egg, ‘On the contrary,’ Fanning answered, ‘I’d be the first to rejoice. If people write, it means they exist; and all I ask for is to be able to pretend that the world doesn’t exist. The wicked flee when no man pursueth. How well I understand them! But letters don’t allow you to be an ostrich. The Freudians say . . .’ He broke off suddenly. After all he was talking to Colin—to Colin. The confessional, self-accusatory manner was wholly misplaced. Pointless to give Colin the excuse to say something disagreeable. But what he had been going to say about the Freudians was amusing. ‘The Freudians,’ he began again.

But taking advantage of forty years of intimacy, Judd had already started to be disagreeable. ‘But you’d be miserable,’ he was saying, ‘if the post didn’t bring you your regular dose of praise and admiration and sympathy and . . .’

‘And humiliation,’ added Fanning, who had opened one of the envelopes and was looking at the letter within. ‘Listen to this. From my American publishers. Sales and Publicity Department. “My dear Mr Fanning.” My dear, mark you. Wilbur F. Schmalz’s dear. “My dear Mr Fanning,—Won’t you take us into your confidence with regard to your plans for the Summer Vacation? What aspect of the Great Outdoors are you favouring this year? Ocean or Mountain, Woodland or purling Lake? I would esteem it a great privilege if you would inform me, as I am preparing a series of notes for the Literary Editors of our leading journals, who are, as I have often found in the past, exceedingly receptive to such personal material, particularly when accompanied by well-chosen snapshots. So won’t you cooperate with us in providing this service? Very cordially yours, Wilbur F. Schmalz.” Well, what do you think of that?’

‘I think you’ll answer him,’ said Judd. ‘Charmingly,’ he added, envenoming his malice. Fanning gave a laugh, whose very ease and heartiness betrayed his discomfort. ‘And you’ll even send him a snapshot.’

Contemptuously—too contemptuously (he felt it at the time)—Fanning crumpled up the letter and threw it into the fireplace. The really humiliating thing, he reflected, was that Judd was quite right: he would write to Mr Schmalz about the Great Outdoors, he would send the first snapshot anybody took of him. There was a silence. Fanning ate two or three spoonfuls of egg. Perfectly boiled, for once. But still, what a relief that Colin was going away! After all, he reflected, there’s a great deal to be said for a friend who has a house in Rome and who invites you to stay, even when he isn’t there. To such a man much must be forgiven—even his infernal habit of being a woodpecker. He opened another envelope and began to read.

Possessive and preoccupied, like an anxious mother, Judd watched him. With all his talents and intelligence, Miles wasn’t fit to face the world alone. Judd had told him so (peck, peck!) again and again. ‘You’re a child!’ He had said it a thousand times. ‘You ought to have somebody to look after you.’ But if any one other than himself offered to do it, how bitterly jealous and resentful he became! And the trouble was that there were always so many applicants for the post of Fanning’s bear-leader. Foolish men or, worse and more frequently, foolish women, attracted to him by his reputation and then conquered by his charm. Judd hated and professed to be loftily contemptuous of them. And the more Fanning liked his admiring bear-leaders, the loftier Judd’s contempt became. For that was the bitter and unforgivable thing: Fanning manifestly preferred their bear-leading to Judd’s.

They flattered the bear, they caressed and even worshipped him; and the bear, of course, was charming to them, until such time as he growled, or bit, or, more often, quietly slunk away. Then they were surprised, they were pained. Because, as Judd would say with a grim satisfaction, they didn’t know what Fanning was really like. Whereas he did know and had known since they were schoolboys together, nearly forty years before. Therefore he had a right to like him—a right and, at the same time, a duty to tell him all the reasons why he ought not to like him. Fanning didn’t much enjoy listening to these reasons; he preferred to go where the bear was a sacred animal. With that air, which seemed so natural on his grey sharp face, of being dispassionately impersonal, ‘You’re afraid of healthy criticism,’ Judd would tell him. ‘You always were, even as a boy.’

‘He’s Jehovah,’ Fanning would complain. ‘Life with Judd is one long Old Testament. Being one of the Chosen People must have been bad enough. But to be the Chosen Person, in the singular . . .’ and he would shake his head. ‘Terrible!’

And yet he had never seriously quarrelled with Colin Judd. Active unpleasantness was something which Fanning avoided as much as possible. He had never even made any determined attempt to fade out of Judd’s existence as he had faded, at one time or another, out of the existence of so many once intimate bear-leaders. The habit of their intimacy was of too long standing and, besides, old Colin was so useful, so bottomlessly reliable. So Judd remained for him the Oldest Friend whom one definitely dislikes; while for Judd, he was the Oldest Friend whom one adores and at the same time hates for not adoring back, the Oldest Friend whom one never sees enough of, but whom, when he is there, one finds insufferably exasperating, the Oldest Friend whom, in spite of all one’s efforts, one is always getting on the nerves of.

‘If only,’ Judd was thinking, ‘he could have faith!’ The Catholic Church was there to help him. (Judd himself was a convert of more than twenty years’ standing.) But the trouble was that Fanning didn’t want to be helped by the Church; he could only see the comic side of Judd’s religion. Judd was reserving his missionary efforts till his friend should be old or ill. But if only, meanwhile, if only, by some miracle of grace . . . So thought the good Catholic; but it was the jealous friend who felt and who obscurely schemed. Converted, Miles Fanning would be separated from his other friends and brought, Judd realized, nearer to himself.

Watching him, as he read his letter, Judd noticed, all at once, that Fanning’s lips were twitching involuntarily into a smile. They were full lips, well cut, sensitive and sensual; his smiles were a little crooked. A dark fury suddenly fell on Colin Judd.

‘Telling me that you’d like to get no letters!’ he said with an icy vehemence. ‘When you sit there grinning to yourself over some silly woman’s flatteries.’

Amazed, amused, ‘But what an outburst!’ said Fanning, looking up from his letter.

Judd swallowed his rage; he had made a fool of himself. It was in a tone of calm dispassionate flatness that he spoke. Only his eyes remained angry. ‘Was I right?’ he asked.

‘So far as the woman was concerned,’ Fanning answered. ‘But wrong about the flattery. Women have no time nowadays to talk about anything except themselves.’

‘Which is only another way of flattering,’ said Judd obstinately. ‘They confide in you, because they think you’ll like being treated as a person who understands.’

‘Which is what, after all, I am. By profession even.’ Fanning spoke with an exasperating mildness. ‘What is a novelist, unless he’s a person who understands?’ He paused; but Judd made no answer, for the only words he could have uttered would have been whirling words of rage and jealousy. He was jealous not only of the friends, the lovers, the admiring correspondents; he was jealous of a part of Fanning himself, of the artist, the public personage; for the artist, the public personage seemed so often to stand between his friend and himself. He hated, while he gloried in them.

Fanning looked at him for a moment, expectantly; but the other kept his mouth tight shut, his eyes averted. In the same exasperatingly gentle tone, ‘And flattery or no flattery,’ Fanning went on, ‘this is a charming letter. And the girl’s adorable.’

He was having his revenge. Nothing upset poor Colin Judd so much as having to listen to talk about women or love. He had a horror of anything connected with the act, the mere thought, of sex. Fanning called it his perversion. ‘You’re one of those