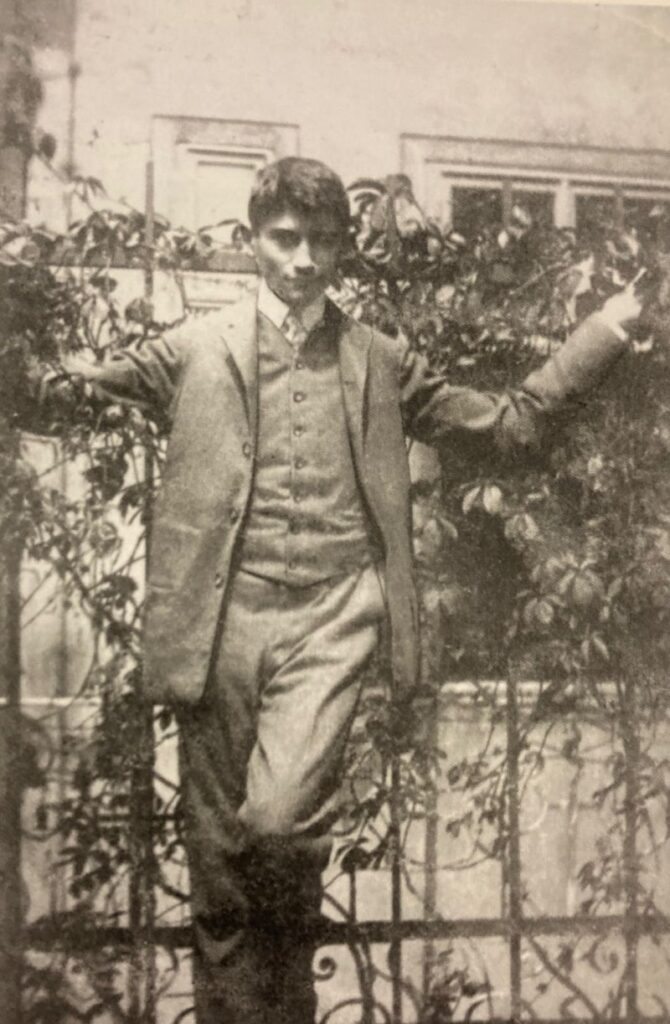

The Castle, Franz Kafka

Contents

1 Arrival

2 Barnabas

3 Frieda

4 First Conversation with the Landlady

5 The Village Mayor

6 Second Conversation with the Landlady

7 The Teacher

8 Waiting for Klamm

9 Opposition to Questioning

10 On the Road

11 At the School

12 The Assistants

13 Hans

14 Frieda’s Grievance

15 At Amalia’s House

16

17 Amalia’s Secret

18 Amalia’s Punishment

19 Petitioning

20 Olga’s Plans

21

22

23

24

25

The Castle

1

Arrival

It was late evening when K. arrived. The village lay deep in snow. There was nothing to be seen of Castle Mount, for mist and darkness surrounded it, and not the faintest glimmer of light showed where the great castle lay. K. stood on the wooden bridge leading from the road to the village for a long time, looking up at what seemed to be a void.

Then he went in search of somewhere to stay the night. People were still awake at the inn. The landlord had no room available, but although greatly surprised and confused by the arrival of a guest so late at night, he was willing to let K. sleep on a straw mattress in the saloon bar. K. agreed to that. Several of the local rustics were still sitting over their beer, but he didn’t feel like talking to anyone.

He fetched the straw mattress down from the attic himself, and lay down near the stove. It was warm, the locals were silent, his weary eyes gave them a cursory inspection, and then he fell asleep.

But soon afterwards he was woken again. A young man in town clothes, with a face like an actor’s—narrowed eyes, strongly marked eyebrows—was standing beside him with the landlord. The rustics were still there too, and some of them had turned their chairs round so that they could see and hear better. The young man apologized very civilly for having woken K., introduced himself as the son of the castle warden, and added: ‘This village belongs to the castle, so anyone who stays or spends the night here is, so to speak, staying or spend-ing the night at the castle.

And no one’s allowed to do that without a permit from the count. However, you don’t have any such permit, or at least you haven’t shown one.’

K. had half sat up, had smoothed down his hair, and was now look-ing up at the two men. ‘What village have I come to, then?’ he asked. ‘Is there a castle in these parts?’

‘There most certainly is,’ said the young man slowly, as some of those present shook their heads at K.’s ignorance. ‘Count Westwest’s* castle.’

‘And I need this permit to spend the night here?’ asked K., as if to convince himself that he had not, by any chance, dreamed the earlier information.

‘Yes, you need a permit,’ was the reply, and there was downright derision at K.’s expense in the young man’s voice as, with arm out-stretched, he asked the landlord and the guests: ‘Or am I wrong? Doesn’t he need a permit?’

‘Well, I’ll have to go and get a permit, then,’ said K., yawning, and throwing off his blanket as if to rise to his feet.

‘Oh yes? Who from?’ asked the young man.

‘Why, from the count,’ said K. ‘I suppose there’s nothing else for it.’ ‘What, go and get a permit from the count himself at midnight?’

cried the young man, retreating a step.

‘Is that impossible?’ asked K., unruffled. ‘If so, why did you wake me up?’

At this the young man was positively beside himself. ‘The manners of a vagrant!’ he cried. ‘I demand respect for the count’s authority! I woke you up to tell you that you must leave the count’s land immediately.’

‘That’s enough of this farce,’ said K. in a noticeably quiet voice. He lay down and pulled the blanket over him. ‘Young man, you’re going rather too far, and I’ll have something to say about your con-duct tomorrow. The landlord and these gentlemen are my witnesses, if I need any. As for the rest of it, let me tell you that I’m the land surveyor,* and the count sent for me.

My assistants will be coming tomorrow by carriage with our surveying instruments. I didn’t want to deprive myself of a good walk here through the snow, but unfor-tunately I did lose my way several times, and that’s why I arrived so late. I myself was well aware, even before you delivered your lecture, that it was too late to present myself at the castle. That’s why I con-tented myself with sleeping the night here, and you have been—to put it mildly—uncivil enough to disturb my slumbers. And that’s all the explanation I’m making. Goodnight, gentlemen.’ And K. turned to the stove.

‘Land surveyor?’ he heard someone ask hesitantly behind his back, and then everyone fell silent. But the young man soon pulled himself together and told the landlord, in a tone just muted enough to sound as if he were showing consideration for the sleeping K., but loud enough for him to hear what was said: ‘I’ll telephone and ask.’ Oh, so there was a telephone in this village inn, was there? They were very well equipped here.

As a detail that surprised K., but on the whole he had expected this. It turned out that the telephone was installed almost right above his head, but drowsy as he was, he had failed to notice it. If the young man really had to make a telephone call, then with the best will in the world he could not fail to disturb K.’s sleep. The only point at issue was whether K. would let him use the tele-phone, and he decided that he would. In which case, however, there was no point in making out that he was asleep, so he turned over on his back again. He saw the locals clustering nervously together and conferring; well, the arrival of a land surveyor was no small matter.

The kitchen door had opened and there, filling the whole doorway, stood the monumental figure of the landlady. The landlord approached on tiptoe to let her know what was going on. And now the telephone conversation began. The warden was asleep, but a deputy warden, or one of several such deputies, a certain Mr Fritz, was on the line.

The young man, who identified himself as Schwarzer, told Mr Fritz how he had found K., a man of very ragged appearance in his thirties, sleeping peacefully on a straw mattress, with a tiny rucksack as a pillow and a gnarled walking-stick within reach. He had naturally felt suspi-cious, said the young man, and as the landlord had clearly neglected to do his duty it had been up to him to investigate the matter. K., he added, had acted very churlishly on being woken, questioned, and threatened in due form with expulsion from the county, although, as it finally turned out, perhaps with some reason, for he claimed to be a land surveyor and said his lordship the count had sent for him. Of course it was at least their formal duty to check this claim, so he, Schwarzer, would like Fritz to enquire in Central Office, find out whether any such surveyor was really expected, and telephone back with the answer at once.

Then all was quiet. Fritz went to make his enquiries, and here at the inn they waited for the answer, K. staying where he was, not even turning round, not appearing at all curious, but looking straight ahead of him. The way Schwarzer told his tale, with a mingling of malice and caution, gave him an idea of what might be called the diplomatic training of which even such insignificant figures in the castle as Schwarzer had a command. There was no lack of industry there either; Central Office was working even at night, and clearly it answered questions quickly, for Fritz soon rang back. His report, however, seemed to be a very short one, for Schwarzer immediately slammed the receiver down in anger. ‘I said as much!’ he cried. ‘There’s no record of any land surveyor; this is a common, lying vagabond and probably worse.’ For a moment K. thought all of them—Schwarzer, the local rustics, the landlord and landlady—were going to fall on him, and to avoid at least the first onslaught he crawled under the blanket entirely.

Then—he slowly put his head out—the telephone rang again and, so it seemed to K., with particular force. Although it was unlikely that this call too could be about K., they all stopped short, and Schwarzer went back to the phone. He listened to an explanation of some length, and then said quietly, ‘A mistake, then? This is very awkward for me. You say the office manager himself telephoned? Strange, strange. But how am I to explain it to the land surveyor now?’*

K. pricked up his ears. So the castle had described him as ‘the land surveyor’. In one way this was unfortunate, since it showed that they knew all they needed to know about him at the castle, they had weighed up the balance of power, and were cheerfully accepting his challenge. In another way, however, it was fortunate, for it confirmed his opinion that he was being underestimated, and would have more freedom than he had dared to hope from the outset. And if they thought they could keep him in a constant state of terror by recogniz-ing his qualifications as a land surveyor in this intellectually super-cilious way, as it certainly was, then they were wrong.

He felt a slight frisson, yes, but that was all.

K. waved away Schwarzer, who was timidly approaching; he declined to move into the landlord’s room, as he was now