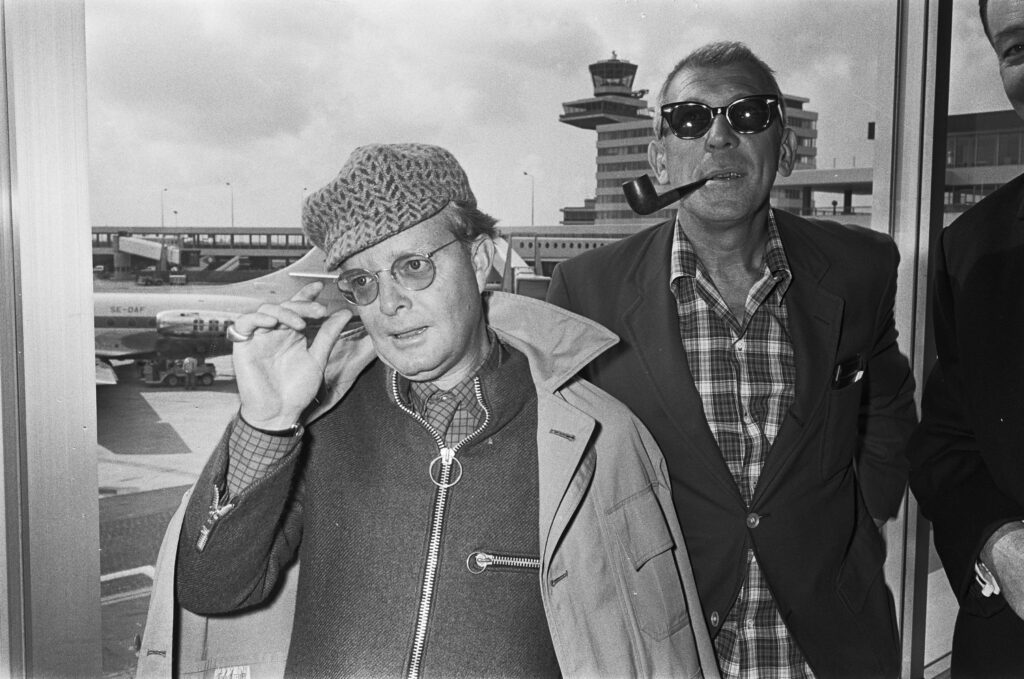

Among the Paths to Eden, Truman Capote

Among the Paths to Eden

One Saturday in March, an occasion of pleasant winds and sailing clouds, Mr. Ivor Belli bought from a Brooklyn florist a fine mass of jonquils and conveyed them, first by subway, then foot, to an immense cemetery in Queens, a site unvisited by him since he had seen his wife buried there the previous autumn. Sentiment could not be credited with returning him today, for Mrs. Belli, to whom he had been married twenty-seven years, during which time she had produced two now-grown and matrimonially-settled daughters, had been a woman of many natures, most of them trying: he had no desire to renew so unsoothing an acquaintance, even in spirit.

No; but a hard winter had just passed, and he felt in need of exercise, air, a heart-lifting stroll through the handsome, spring-prophesying weather; of course, rather as an extra dividend, it was nice that he would be able to tell his daughters of a journey to their mother’s grave, especially so since it might a little appease the elder girl, who seemed resentful of Mr. Belli’s too comfortable acceptance of life as lived alone.

The cemetery was not a reposeful, pretty place; was, in fact, a damned frightening one: acres of fog-colored stone spilled across a sparsely grassed and shadeless plateau. An unhindered view of Manhattan’s skyline provided the location with beauty of a stage-prop sort—it loomed beyond the graves like a steep headstone honoring these quiet folk, its used-up and very former citizens: the juxtaposed spectacle made Mr. Belli, who was by profession a tax accountant and therefore equipped to enjoy irony however sadistic, smile, actually chuckle—yet, oh God in heaven, its inferences chilled him, too, deflated the buoyant stride carrying him along the cemetery’s rigid, pebbled paths.

He slowed until he stopped, thinking: “I ought to have taken Morty to the zoo”; Morty being his grandson, aged three. But it would be churlish not to continue, vengeful: and why waste a bouquet? The combination of thrift and virtue reactivated him; he was breathing hard from hurry when, at last, he stooped to jam the jonquils into a rock urn perched on a rough gray slab engraved with Gothic calligraphy declaring that

SARAH BELLI

1901–1959

had been the

DEVOTED WIFE OF IVOR

BELOVED MOTHER OF IVY AND REBECCA.

Lord, what a relief to know the woman’s tongue was finally stilled. But the thought, pacifying as it was, and though supported by visions of his new and silent bachelor’s apartment, did not relight the suddenly snuffed-out sense of immortality, of glad-to-be-aliveness, which the day had earlier kindled. He had set forth expecting such good from the air, the walk, the aroma of another spring about to be. Now he wished he had worn a scarf; the sunshine was false, without real warmth, and the wind, it seemed to him, had grown rather wild. As he gave the jonquils a decorative pruning, he regretted he could not delay their doom by supplying them with water; relinquishing the flowers, he turned to leave.

A woman stood in his way. Though there were few other visitors to the cemetery, he had not noticed her before, or heard her approach. She did not step aside. She glanced at the jonquils; presently her eyes, situated behind steel-rimmed glasses, swerved back to Mr. Belli.

“Uh. Relative?”

“My wife,” he said, and sighed as though some such noise was obligatory.

She sighed, too; a curious sigh that implied gratification. “Gee, I’m sorry.”

Mr. Belli’s face lengthened. “Well.”

“It’s a shame.”

“Yes.”

“I hope it wasn’t a long illness. Anything painful.”

“No-o-o,” he said, shifting from one foot to the other. “In her sleep.” Sensing an unsatisfied silence, he added, “Heart condition.”

“Gee. That’s how I lost my father. Just recently. Kind of gives us something in common. Something,” she said, in a tone alarmingly plaintive, “something to talk about.”

“—know how you must feel.”

“At least they didn’t suffer. That’s a comfort.”

The fuse attached to Mr. Belli’s patience shortened. Until now he had kept his gaze appropriately lowered, observing, after his initial glimpse of her, merely the woman’s shoes, which were of the sturdy, so-called sensible type often worn by aged women and nurses. “A great comfort,” he said, as he executed three tasks: raised his eyes, tipped his hat, took a step forward.

Again the woman held her ground; it was as though she had been employed to detain him. “Could you give me the time? My old clock,” she announced, self-consciously tapping some dainty machinery strapped to her wrist, “I got it for graduating high school. That’s why it doesn’t run so good any more. I mean, it’s pretty old. But it makes a nice appearance.”

Mr. Belli was obliged to unbutton his topcoat and plow around for a gold watch embedded in a vest pocket. Meanwhile, he scrutinized the lady, really took her apart. She must have been blond as a child, her general coloring suggested so: the clean shine of her Scandinavian skin, her chunky cheeks, flushed with peasant health, and the blueness of her genial eyes—such honest eyes, attractive despite the thin silver spectacles surrounding them; but the hair itself, what could be discerned of it under a drab felt hat, was poorly permanented frizzle of no particular tint. She was a bit taller than Mr. Belli, who was five-foot-eight with the aid of shoe lifts, and she may have weighed more; at any rate he couldn’t imagine that she mounted scales too cheerfully. Her hands: kitchen hands; and the nails: not only nibbled ragged, but painted with a pearly lacquer queerly phosphorescent.

She wore a plain brown coat and carried a plain black purse. When the student of these components recomposed them he found they assembled themselves into a very decent-looking person whose looks he liked; the nail polish was discouraging; still he felt that here was someone you could trust.

As he trusted Esther Jackson, Miss Jackson, his secretary. Indeed, that was who she reminded him of, Miss Jackson; not that the comparison was fair—to Miss Jackson, who possessed, as he had once in the course of a quarrel informed Mrs. Belli, “intellectual elegance and elegance otherwise.” Nevertheless, the woman confronting him seemed imbued with that quality of good-will he appreciated in his secretary, Miss Jackson, Esther (as he’d lately, absent-mindedly, called her). Moreover, he guessed them to be about the same age: rather on the right side of forty.

“Noon. Exactly.”

“Think of that! Why, you must be famished,” she said, and unclasped her purse, peered into it as though it were a picnic hamper crammed with sufficient treats to furnish a smörgåsbord. She scooped out a fistful of peanuts. “I practically live on peanuts since Pop—since I haven’t anyone to cook for. I must say, even if I do say so, I miss my own cooking; Pop always said I was better than any restaurant he ever went to. But it’s no pleasure cooking just for yourself, even when you can make pastries light as a leaf.

Go on. Have some. They’re fresh-roasted.”

Mr. Belli accepted; he’d always been childish about peanuts and, as he sat down on his wife’s grave to eat them, only hoped his friend had more. A gesture of his hand suggested that she sit beside him; he was surprised to see that the invitation seemed to embarrass her; sudden additions of pink saturated her cheeks, as though he’d asked her to transform Mrs. Belli’s bier into a love bed.

“It’s okay for you. A relative. But me. Would she like a stranger sitting on her—resting place?”

“Please. Be a guest. Sarah won’t mind,” he told her, grateful the dead cannot hear, for it both awed and amused him to consider what Sarah, that vivacious scene-maker, that energetic searcher for lipstick traces and stray blond strands, would say if she could see him shelling peanuts on her tomb with a woman not entirely unattractive.

And then, as she assumed a prim perch on the rim of the grave, he noticed her leg. Her left leg; it stuck straight out like a stiff piece of mischief with which she planned to trip passers-by. Aware of his interest, she smiled, lifted the leg up and down. “An accident. You know. When I was a kid. I fell off a roller coaster at Coney. Honest. It was in the paper. Nobody knows why I’m alive. The only thing is I can’t bend my knee. Otherwise it doesn’t make any difference. Except to go dancing. Are you much of a dancer?”

Mr. Belli shook his head; his mouth was full of peanuts.

“So that’s something else we have in common. Dancing. I might like it. But I don’t. I like music, though.”

Mr. Belli nodded his agreement.

“And flowers,” she added, touching the bouquet of jonquils; then her fingers traveled on and, as though she were reading Braille, brushed across the marble lettering on his name. “Ivor,” she said, mispronouncing it. “Ivor Belli. My name is Mary O’Meaghan. But I wish I were Italian. My sister is; well, she married one. And oh, he’s full of fun; happy-natured and outgoing, like all Italians. He says my spaghetti’s the best he’s ever had. Especially the kind I make with sea-food sauce. You ought to taste it.”

Mr. Belli, having finished the peanuts, swept the hulls off his lap. “You’ve got a customer. But he’s not Italian. Belli sounds like that. Only I’m Jewish.”

She frowned, not with disapproval, but as if he had mysteriously daunted her.

“My family came from Russia; I was born there.”

This last information restored her enthusiasm, accelerated it. “I don’t care what they say in the papers. I’m sure Russians are the same as everybody else.