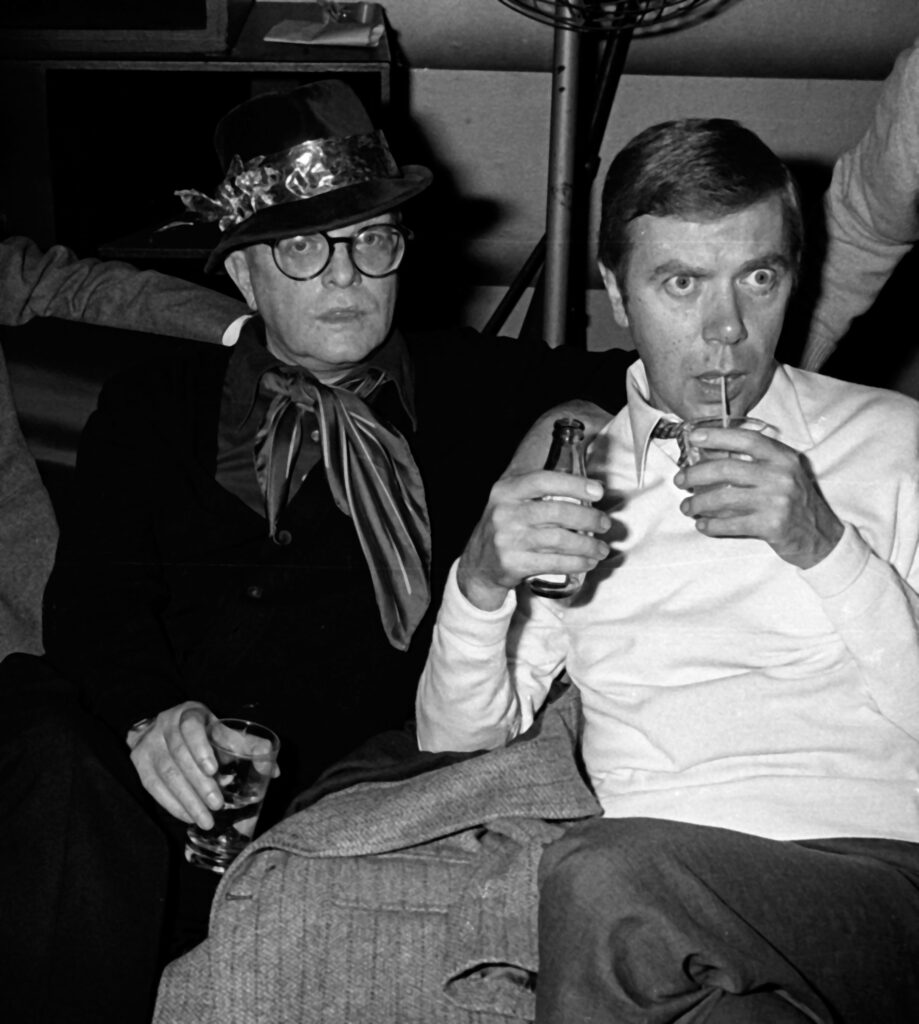

Cecil Beaton, Truman Capote

CECIL BEATON

To call a book The Best of Beaton is catchy enough, but inaccurate—unless some one book could contain fine specimens of Beaton’s many facets: his stage décors, his costume designs, sketches and paintings, pages reprinted from his very remarkable journals and at least several verbatim samples of his conversational gifts, for surely Cecil is one of the few surviving artists in this increasingly obsolete area.

I don’t know, I’ve never asked him, but I suspect Cecil would prefer to be remembered for his talents in mediums other than photography—a phenomenon quite common with persons who develop multiple gifts: they often prefer to rather slight the original one. It might be said that Beaton was without any central talent until, as a very ambitious but unsensible young man of great sensibility, he started using a camera: it was the camera, curiously enough, that released all the subtler creative strains.

And for all the documented brilliance of his other muses, it is as a photographer that Beaton attains cultural importance—not only because of the individual excellence of his own work, but because of its influence on the work of the finest photographers of the last two generations: whether or not they admit it, or are even conscious of it, there is almost no first-rate contemporary photographer of any nationality who is not to some degree indebted to Cecil Beaton. Why? Look at the pictures. Even the earliest ones presage future influence on a multitude of camera-artists.

For instance, the portraits of Lady Oxford and Edith Sitwell made in the twenties: no one had photographed faces in quite this manner before, surrounded them with such neoromantic, stylized décor (spun glass, masked statues, pastry molds and extravagant costumes: all the appurtenances of Beaton’s own surrealism) or lighted them with such lacquered luminosity. And the thing is, these portraits have not “dated,” not even, in a technical sense, the so-called “fashion” photographs. (The attitude of photographers toward fashion photography, and the position it holds in their careers, is an ambiguous business.

With the exception of Cartier-Bresson, a man of independent means, I can’t offhand recall a single photographer seriously making a livelihood out of his trade who doesn’t work extensively for either fashion magazines or advertising agencies. And why not? It disciplines the artist and forces his invention. Beaton, like many others, owes a number of his most interesting photographs to the limitations imposed by purely commercial factors. But photographers as a breed seem not to gain much satisfaction from their labors in such vineyards—I don’t mean Beaton: he is too much a craftsman and too unpretentious not to be grateful for the merit of his work in whatever style.)

But again, this question of unyellowing, of the timeless quality in these pictures. Of course, in some instances Beaton has already pre-aged his portraits by setting them in the past—for example, the various pastiche of Victorian daguerreotype: the combination of modern with long-ago creates its own time—suspension. But when one speaks of the timeless, this is not what one means. Then what does one mean? Well, any in the series Beaton calls Time Sequences—subjects he has had the opportunity to photograph over periods extending as much as four decades.

One observes a slowly thickening, but ever lustrous, rather maniacal-eyed Picasso; an Auden, starting off like a duly wrinkled bloodhound pup and ending looking like the hound’s sagging, tobacco-stained sire; or Cocteau, fragile and fresh and expensive as a sprig of muguet in January, then later, with his jeweled fingers, seeming an animated Proustian souvenir. None of these studies is dependent for its effect upon its relation to the rest of the sequence; separated, any one of them seems an ageless and definitive image of the man. Yet how eerie, and sad, yet how exhilarating to see these faces as they flow through time—frozen by sensitively manipulated light and shadow.

It is not difficult to discern Beaton’s influence in the work of others: a harder task is to identify those who have influenced him. Obviously he is indebted to Baron de Meyer, that original and tragic artist who contributed photographs of a pioneer stylishness to the earlier issues of Vanity Fair. Beaton, with his own sense of elegance, was the first direct descendant of the late Baron. And Beaton admired Steichen; but name a photographer not obliged to Steichen. To my mind, Beaton’s work does not reflect artistic sources as much as it does his private social interests and the temperaments of his times. For example, in 1938 and 1939 Beaton photographed a contingent of personalities not amid flowers and the sleek apparatus of the studios, but through the broken windows of abandoned sinister houses and factories.

These photographs are like fever charts of the future, a prediction of the bombs soon to explode.

Speaking of which, one of Beaton’s most distinguished and versatile achievements is his war photographs, these smoky pictures of London asunder, of violent skies and bandaged children: here the artist produces a brutal poignance, a harsher color, than the viewer usually associates with his photographic palette. This is also true of Beaton’s photographs of India and China, countries in which he served during the war. A pity, for though these are not military pictures in the sense that Cim’s or Capa’s were, they are nevertheless war documents of painful poetic insight which illustrate a side of Beaton insufficiently recognized. Nowadays a professional photographer is by necessity almost a professional traveler: editors with commissions hustle them on to jets that hustle them around the world in pursuit of Lord knows what.

Even the feeblest talents are subsidized in this manner (and may I say in passing that ninety percent—make that ninety-five—of fully employed photographers are feeble indeed: an amazing racket, really, and even a few of the very few genuinely gifted photographers secretly consider themselves racketeers). But Cecil has always been a determined roamer, and as a youth wandered by cargo boat from Haiti to Morocco.

Myself, also a footloose fellow, I’ve run into Mr. B. in the damnedest places. On the beach at Waikiki—with hula music in the background. In a Sicilian olive grove, in a Greek monastery, in the lobby of the Barcelona Ritz, by the pool at the Bel Air Hotel, at a café table in the Tangier Casbah, on a junk in the Hong Kong bay, backstage at a Broadway musical, on a téléphérique climbing a Swiss alp, in a geisha house in Kyoto, among the ruins of Angkor Wat, the temples of Bangkok, aboard Daisy Fellowes’s yacht Sister Ann, in a Harlem night club, a Venetian palazzo, a Parisian antiquaire, a London shoeshop, and so forth on and on.

The point is, I’ve observed Beaton in all climates, mental and otherwise, and have often had the privilege of watching him work with a camera—actually, we have once in a while collaborated: my text accompanying his photographs. I’ve had that sort of experience with other photographers, particularly Henri Cartier-Bresson and Richard Avedon—both of whom I respect extremely: with Beaton added, I consider that they ought to occupy the first three places in any list of the world’s superior photographers.

But how differently each man operates! Avedon is primarily a studio photographer; at any rate, he seems at his most creative ease in the midst of perfectly functioning machinery and attentive assistants.

Rather recently I worked with Avedon, under primitive conditions, on a story in the American Midwest; he had no assistant and was using a newfangled Japanese camera that was capable of taking a hundred-odd exposures before the film needed changing. We slaved the whole of one morning, drove many a mile through heat and dust, and then, when we returned to the motel where we were staying, Avedon, with a jittery little laugh, suddenly announced that all our labor was for naught: it had been so many years since he had worked without assistants, who always prepared his cameras, that he had forgot to put any film in the Japanese job.

Cartier-Bresson is another tasse de thé entirely—self-sufficient to a fault. I remember once watching Bresson at work on a street in New Orleans—dancing along the pavement like an agitated dragonfly, three Leicas swinging from straps around his neck, a fourth one hugged to his eye: click-click-click (the camera seems a part of his own body), clicking away with a joyous intensity, a religious absorption. Nervous and merry and dedicated, Bresson is an artistic “loner,” a bit of a fanatic.

But not Beaton. This man, with his cool (sometimes cold) blue eyes and palely lifted eyebrows, is as casual and detached as he seems: with a camera in his hand, he just knows what he is doing, that’s all, has no need for a lot of temper and attitudinizing. Unlike many of his colleagues, I’ve never heard Cecil talk about Technique or Art or Honesty. He simply takes pictures and hopes to be paid for them. But the way in which he works is very special to him. One of the immediately striking things about Beaton’s personal behavior is the manner in which he creates an illusion of time-without-end.

Though he is apparently always under the pressure of a disheartening schedule, one would never suppose he wasn’t a gentleman of almost tropical leisure: if he has ten minutes to catch a plane, and yet is speaking with you on the telephone, he does nothing to shorten the call but continues to indulge in a luxury of marvelous manners. Nevertheless, you can be damn sure he will make that plane. As with the caller, so it is with the sitter: a person sitting for Beaton