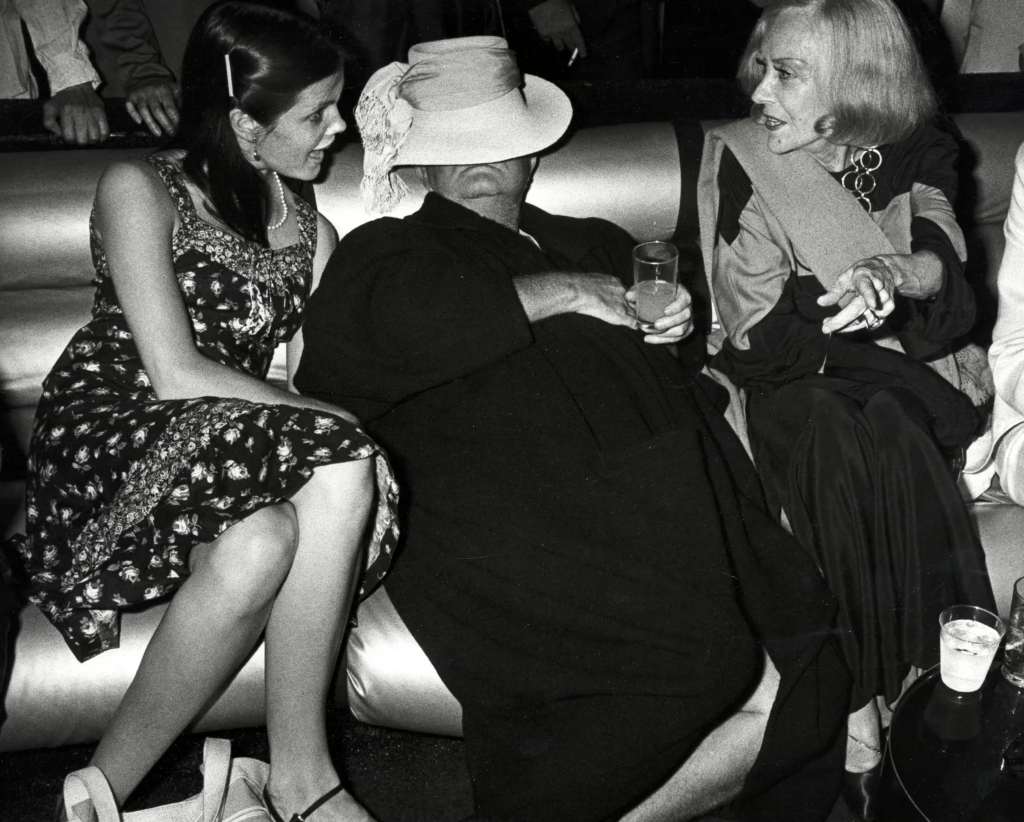

Hollywood, Truman Capote

HOLLYWOOD

Approaching Los Angeles, at least by air, is like, I should imagine, crossing the surface of the moon: prehistoric shapes, looming in stone ripples and corroded, leer upward, and paleozoic fish swim in the shadowy pools between desert mountains: burned and frozen, there is no living thing, only rock that was once a bird, bones that are sand, ferns turned to fiery stone.

At last a welcoming fleet of clouds: we have crept between a sorcerer’s passage, snow is on the mountains, yet flowers color the land, a summer sun juxtaposes December’s winter sea, down, down, the plane splits through plumed, gold, incredible air.

Oh, moaned Thelma, I can’t stand it, she said, and poured a cascade of Chiclets into her mouth. Thelma had boarded the plane in Chicago; she was a young Negro girl, rather pretty, beautifully dressed, and it was the most wonderful thing that would ever happen to her, this trip to California. “I know it, it’s going to be just grand. Three years I’ve been ushering at the Lola Theater on State Street just to save the fare.

My auntie tells the cards, and she said—Thelma, honey, head for Hollywood ’cause there’s a job as private secretary to a movie actress just waiting for you. She didn’t say what actress, though. I hope it’s not Esther Williams. I don’t like swimming much.”

Later on she asked if I was trying for film work, and because the idea seemed to please her, I said yes. On the whole she was very encouraging, and assured me that as soon as she was established as a private secretary, thereby having access to the ears of the great, she would not forget me, would indeed give me every assistance.

At the airport I helped with her luggage, and eventually we shared a taxi. It came about then that she had no place specific to go, she simply wanted the driver to let her off in the “middle” of Hollywood. It was a long drive, and she sat all the way on the edge of the seat, unbearably watchful.

But there was not so much to see as she’d imagined. “It don’t look correct,” she said finally, quite as if we’d been played a wretched trick, for here again, though in disguise, was the surface of the moon, the noplace of everywhere; but how very correct, after all, that here at continent’s end we should find only a dumping ground for all that is most exploitedly American: oil pumps pounding like the heartbeat of demons, avenues of used-car lots, supermarkets, motels, the gee dad I never knew a Chevrolet gee dad gee mom gee whiz wham of publicity, the biggest, broadest, best, sprawled and helplessly etherized by immaculate sunshine and sound of sea and unearthly sweetness of flowers blooming in December.

During the drive the sky had grown ash-colored, and as we turned into the laundered sparkle of Wilshire Boulevard, Thelma, giving her delicate feathered hat a protective touch, grumbled at the possibility of rain. Not a chance, said the driver, just wind blowing in dust from the desert. These words were not out of his mouth before the palm trees shivered under a violent downpour.

But Thelma had no place to go, except into the street, so we left her standing there, rain pulling her costume apart. When a traffic light stopped us at the corner, she ran up and stuck her head in the window. “Look here, honey, remember what I say, you get hungry or anything you just find where I’m at.” Then, with a lovely smile, “And listen, honey, lotsa luck!”

December 3. Today, through the efforts of a mutual friend, Nora Parker, I was asked to lunch by the fabled Miss C. There is a fortress wall surrounding her place, and at the entrance gate we were more or less frisked by a guard who then telephoned ahead to announce our arrival. All this was very satisfying; it was nice to know that at least someone was living the way a famous actress should.

At the door we were met by a red-faced, overly nourished child with a gooey pink ribbon trailing from her hair. “Mummy thinks I should entertain you till she comes down,” she said apathetically, then led us into a large and, now that I think about it, preposterous room: it looked as though some rich old rascal had personally decorated himself a lavish hideaway: sly, low-slung couches, piles of lecherous velvet pillows and lamps with sinuous, undulating shapes. “Would you like to see Mummy’s things?” said the little girl.

Her first exhibit was an illuminated bibelot cabinet. “This,” she said, pointing to a bit of Chinese porcelain, “is Mummy’s ancient vase she paid Gump’s three thousand dollars for. And that’s her gold cocktail shaker and gold cups. I forget how much they cost, an awful lot, maybe five thousand dollars. And you see that old teapot? You wouldn’t believe what it’s worth …”

It was a monstrous recital, and toward the end of it, Nora, looking dazedly round the room for a change of topic, said, “Such lovely flowers. Are they from your own garden?”

“Heavens, no,” replied the little girl disdainfully. “Mummy orders them every day from the most expensive florist in Beverly Hills.”

“Oh?” said Nora, wincing. “And what is your favorite flower?”

“Orchids.”

“Now really. I don’t believe orchids could be your favorite flower. A little girl like you.”

She thought a moment. “Well, as a matter of fact, they aren’t. But Mummy says they are the most expensive.”

Just then there was a rustling at the door; Miss C. skipped like a schoolgirl across the room: her famous face was without make-up; hairpins dangled loosely. She was wearing a very ordinary flannel housecoat. “Nora, darling,” she called, her arms outstretched, “do forgive my being so long. I’ve been upstairs making the beds.”

Yesterday, feeling greedy, I remembered ravishing displays of fruit outside a large emporium I’d driven admiringly past a number of times. Mammoth oranges, grapes big as ping-pong balls, apples piled in rosy pyramids. There is a sleight of hand about distances here, nothing is so near as you supposed, and it is not unusual to travel ten miles for a package of cigarettes.

It was a two-mile walk before I even caught sight of the fruit store. The long counters were tilted so that from quite far away you could see the splendid wares, apples, pears. I reached for one of these extraordinary apples, but it seemed to be glued into its case. A salesgirl giggled. “Plaster,” she said, and I laughed too, a little feverishly perhaps, then wearily followed her into the deeper regions of the store, where I bought six small, rather mealy apples, and six small, rather mealy pears.

It is Christmas week. And it is evening now a long time. Below the window a lake of light bulbs electrifies the valley. From the haunting impermanence of their hilltop homes impermanent eyes are watching them, almost as if suddenly they might go out, like candles at last consumed.

Earlier today I took a bus all the way from Beverly Hills into downtown Los Angeles. The streets are strung with garlands, we passed a motorized sleigh that was spinning along spilling a wake of white cornflakes, at corners sweating woolly men rustle bells under the shade of prefabricated trees; carols, hurled from lamppost loudspeakers, pour their syrup on the air, and tinsel, twinkling in twenty-four-karat sunshine, hangs everywhere like swamp moss.

It could not be more Christmas, or less so. I once knew a woman who imported a pink villa stone by stone from Italy and had it reconstructed on a demure Connecticut meadow: Christmas is as out of place in Hollywood as the villa was in Connecticut. And what is Christmas without children, on whom so much of the point depends? Last week I met a man who concluded a set of observations by saying, “And of course you know this is the childless city.”

For five days I have been testing his remark, casually at first, now with morbid alarm; preposterous, I know, but since commencing this mysterious campaign I have seen less than half a dozen children. But first, a relevant point: a primary complaint here is overpopulation; old-guard natives tell me the terrain is bulging with “undesirable” elements, hordes of ex-soldiers, workers who moved here during the war, and those spiritual Okies, the young and footloose; yet walking around I sometimes have the feeling of one who awakened some eerie morning into a hushed, deserted world where overnight, like sailors aboard the Marie Celeste, all souls had disappeared.

There is an air of Sunday vacancy; here where no one walks cars glide in a constant shiny silent stream, my shadow, moving down the stark white street, is like the one living element of a Chirico. It is not the comfortable silence felt in small American towns, though the physical atmosphere of stoops and yards and hedges is very often the same; the difference is that in real towns you can be pretty sure what sorts of people there are hiding beyond those numbered doors, but here, where all seems transient, ephemeral, there is no general pattern to the population, and nothing is intended—this street, that house, mushrooms of accident, and a crack in the wall, which might somewhere else have charm, only strikes an ugly note prophesying doom.

- A teacher here recently gave a vocabulary test in which she asked her students to provide the antonym of youth. Over half the class answered death.

- No stylish Hollywood home is thought quite sanitary without a brace of