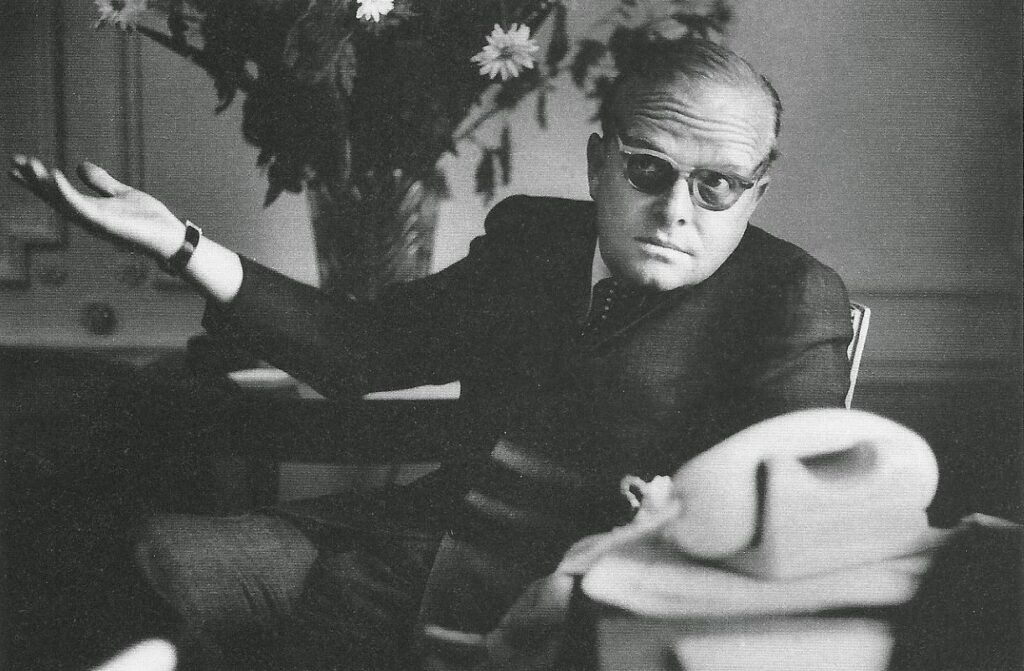

Mill Store, Truman Capote

Mill Store

The woman gazed out of the back window of the Mill Store, her attention rapt upon the children playing happily in the bright water of the creek.

The sky was completely cloudless, and the southern sun was hot on the earth. The woman wiped the sweat off her forehead with a red handkerchief.

The water, rushing rapidly over the bright creek bottom pebbles, looked cold and inviting. If those picnickers weren’t down there now, she thought, I swear I’d go and sit in that water and cool myself off. Whew—!

Almost every Saturday people would come from the town on picnic parties and spend the afternoon feasting on the white pebbled shores of Mill Creek, while their children waded in the semi-shallow water.

This afternoon, a Saturday late in August, there was a Sunday school picnic in progress. Three elderly women, Sunday school teachers, rushed about the shady spot, anxiously tending their young charges.

The woman, watching from the Mill Store, turned her gaze back into the comparatively dark interior of the store and searched around for a pack of cigarettes.

She was a big woman, dark and sunburned. Her black hair was thick but cut short. She was dressed in a cheap calico dress.

As she lighted her cigarette she frowned over the smoke. She twisted her mouth and grimaced. That was the only trouble with this damn smoking; it hurt the ulcers in her mouth. She inhaled sharply, the suction easing the stinging sores for the moment.

It must be the water, she thought. I ain’t used to drinkin’ this well water. She had only come to the town three weeks ago, looking for a job. Mr. Benson had given her the job, a chance to work in the Mill Store.

She didn’t like it here. It was five miles to the town, and she wasn’t exactly prone to walking. It was too quiet, and at night, when she heard the crickets chirping and the bull frogs croaking their lonely cry, she would get the “jitters.”

She glanced at the cheap alarm clock. It was three-thirty, the loneliest, most interminable hour of the day for her.

The store was a stuffy place, smelling of kerosene and fresh cornmeal and stale candies. She leaned back out the window. The August mid-afternoon sun hung hot in the sky.

The store was on a sharp red clay bank that rose straight from the creek. At one side there was a big crumbling mill that no one had used for six or seven years.

A rickety, gray wood dam held out the pond waters from the creek which flowed like an opalescent olive ribbon through the woods.

The picnickers had to pay a dollar at the store for the use of the grounds and for fishing in the pond above the dam.

One day she had gone fishing at the pond but all she had caught were a couple of skinny, bony cat-fish and two moccasins.

How she had screamed when she pulled the snakes up, twisting, flashing their slimy bodies in the sun, their poisonous, cotton mouths sunk into her hook.

After the second one, she had dropped her pole and line, rushed back to the store and spent the rest of the humid day consoling herself with movie magazines and a bottle of bourbon.

She thought about it as she looked down at the children splashing in the water. She laughed a little, but just the same she was afraid of the slimy things.

Suddenly a shy young voice behind her said, “Miss—?”

She was startled; she jumped around with a fierce look in her eye. “Ya don’t have to sneak—oh, what d’you want, Kid?”

A little girl pointed to an old fashioned glass show case, filled with cheap candies—jelly beans, gum drops, peppermint sticks, jaw-breakers scattered about the case.

As the child pointed to each desired article the woman reached in and threw it in a small, brown paper bag. The woman watched the child intensely as she chose her purchases. She reminded her of someone. It was the child’s eyes. They were bright, like bubbles of blue glass. Such a pale, sky blue.

The little girl’s hair dipped in waves almost down to her shoulders. It was fine, honey-colored hair. Her legs and face and arms were dark brown, almost too dark. The woman knew the child must have been out in the sun a great deal. She couldn’t help staring at her.

The little girl looked up from her purchasing and asked shyly, “Is something wrong with me?” She looked around her dress to see if it was torn.

The woman was embarrassed. She looked down quickly and began to roll up the end of the bag. “Why, no—no—not at all.”

“Oh, I thought there was because you was looking at me so funny.” The child seemed reassured.

The woman leaned over the counter as she handed the bag to the little girl and touched her hair. She just had to; it seemed so rich, like sweet yellow butter.

“What’s your name, Kid?” she asked.

The child looked frightened. “Elaine,” she said. She grabbed the bag, laid some hot coins on the counter and hurried quickly out of the store.

“Bye, Elaine,” the woman called, but the little girl was already out of the store and hurrying across the bridge to rejoin her playmates.

That’s a helluva thing, she thought. That kid’s eyes are just like his. Those damned eyes. She sat down in a chair in the corner of the store, took one last drag on the cigarette and crushed it lifeless on the bare floor. She pressed her head into her lap and fell into a hot semi-sleep. God, she thought as she dozed, those eyes and, she moaned, these damned ulcers.

She was awakened by four young boys shaking her shoulders and jumping around the store in a frenzy of excitement. “Wake up,” they yelled. “Wake up.”

She looked at them, bleary-eyed for a moment. Her cheeks were hot all over. The ulcers burned in her mouth. She swept them carelessly with her tongue.

“What’sa matter?” she asked, “What’sa matter?”

“Have you got a telephone or a car, Lady, please?” asked one of the excited boys.

“No, no I haven’t,” she said, now fully awake. “What’s the matter? What’s happened? Dam hasn’t burst, has it?”

The boys jumped around. They were too excited to stand still; they just jumped around moaning, “Oh, what are we gonna do! She’ll die, she’ll die!”

The woman was getting mad. “What the hell’s happened, anyway? Tell me, but quick!”

“A kid’s been snake bit,” sobbed a small, chubby boy.

“For God’s sake, where?”

“Down in the creek,” he pointed toward the window.

The woman rushed out the store. Across the bridge she flew and down the pebbled beach. A crowd of people were gathered at the end of the beach.

One of the Sunday school teachers was flying around the crowd, yelling her head off. Some of the children stood to one side, wall-eyed with horror and amazement at this thing that had broken up their party.

The woman broke through the crowd and saw the child that lay on the sand. It was the girl with the bubble eyes, like bright blue glass. “Elaine,” cried the woman.

Everyone turned their attention on the new arrival. She knelt down beside the child and looked at the wound. Already it was swelling and turning color. The child shivered and wept and hit her head with her hand.

“Haven’t you got a car?” the woman asked one of the school teachers. “How did you get here?”

“We hiked over,” the other woman answered, fear and bewilderment in her eyes.

The woman rang her hands in rage. “Look here,” she said, “this kid’s serious; she’s liable to die.”

They all only stared at her. What could they do? They were helpless, just three silly women and a lot of children.

“All right, all right,” the woman cried. “You, you run up to the place and get a coupla chickens. You women get somebody to start running back to town to get a doctor. Hurry, hurry. We haven’t got a minute to lose.”

“But what can we do now for the child?” one of the women asked.

“I’ll show you,” the woman said.

She knelt down beside the little girl and looked at the wound. The place was swollen big now. Without a moment’s hesitation the woman bent over and sunk her mouth against the wound. She sucked and sucked, letting up every few seconds and spitting out a mouthful of fluid.

There were only a few children left and one of the teachers. They stared with horrified fascination and admiration. The child’s face turned the color of chalk and she fainted. The woman spat out mouthfuls of saliva mixed with the poison. Finally she got up and ran to the stream. Rinsing her mouth out with the water, she gurgled furiously.

The children with the chickens arrived. Three big fat hens. The woman grabbed one of them by the legs, and with the aid of a jackknife ripped it open, the hot blood running over everything. “The blood draws what poison there is left, out,” she explained.

When that chicken had turned green she ripped open another and placed it against the child’s wound.

“Come on now,” she said. “Get hold of her and carry her up to the store. We’ll wait there until the doctor comes.

The children ran eagerly forward and with their combined efforts, managed to carry her comfortably. They were crossing the bridge when the school teacher said, “Really, I don’t know how we can ever thank you. It was so, it was—”

The woman pushed her aside and hurried