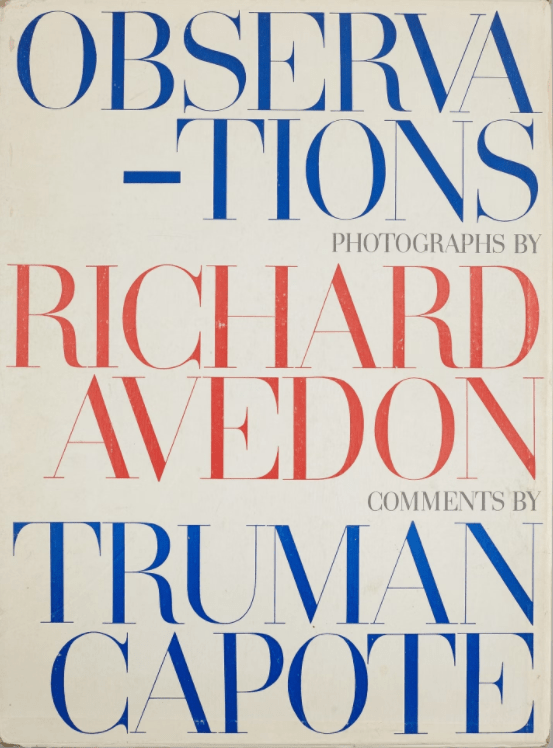

Observations, Truman Capote

OBSERVATIONS

Richard Avedon

John Huston

Charlie Chaplin

A Gathering of Swans

Pablo Picasso

Coco Chanel

Marcel Duchamp

Jean Cocteau and André Gide

Mae West

Louis Armstrong

Humphrey Bogart

Ezra Pound

Somerset Maugham

Isak Dinesen

(with Richard Avedon)

1959

RICHARD AVEDON

Richard Avedon is a man with gifted eyes. An adequate description; to add is sheer flourish. His brown and deceivingly normal eyes, so energetic at seeing the concealed and seizing the spirit, pursuing the flight of a truth, a mood, a face, are the important features: those, and his born-to-be absorption in his craft, photography, without which the unusual eyes, and the nervously sensitive intelligence supplying their power, could not dispel what they distillingly imbibe. For the truth is, though loquacious, an unskimping conversationalist, the sort that zigzags like a bee ambitious to de-pollen a dozen blossoms simultaneously, Avedon is not, not very, articulate: he finds his proper tongue in silence, and while maneuvering a camera—his voice, the one that speaks with admirable clarity, is the soft sound of the shutter forever freezing a moment focused by his perception.

He was born in New York, and is thirty-six, though one would not think it: a skinny, radiant fellow who still hasn’t got his full growth, animated as a colt in Maytime, just a lad not long out of college. Except that he never went to college, never, for that matter, finished high school, even though he appears to have been rather a child prodigy, a poet of some talent, and already, from the time he was ten and the owner of a box camera, sincerely embarked on his life’s labor: the walls of his room were ceiling to floor papered with pictures torn from magazines, photographs by Muncaczi and Steichen and Man Ray.

Such interests, special in a child, suggest that he was not only precocious but unhappy; quite happily he says he was: a veteran at running away from home. When he failed to gain a high-school diploma, his father, sensible man, told him to “Go ahead! Join the army of illiterates.” To be contrary, but not altogether disobedient, he instead joined the Merchant Marine. It was under the auspices of this organization that he encountered his first formal photographic training. Later, after the war, he studied at New York’s New School for Social Research, where Alexey Brodovitch, then Art Director of the magazine Harper’s Bazaar, conducted a renowned class in experimental photography.

A conjunction of worthy teacher with worthy pupil: in 1945, by way of his editorial connection, Brodovitch arranged for the professional debut of his exceptional student. Within the year the novice was established; his work, now regularly appearing in Harper’s Bazaar and Life and Theatre Arts, as well as on the walls of exhibitions, was considerably discussed, praised for its inventive features, its tart insights, the youthful sense of movement and blood-coursing aliveness he could insert in so still an entity as a photograph: simply, no one had seen anything exactly comparable, and so, since he had staying power, was a hard worker, was, to sum it up, seriously gifted, very naturally he evolved to be, during the next decade, the most generously remunerated, by and large successful American photographer of his generation, and the most, as the excessive number of Avedon imitators bears witness, aesthetically influential.

“My first sitter,” so Avedon relates, “was Rachmaninoff. He had an apartment in the building where my grandparents lived. I was about ten, and I used to hide among the garbage cans on his back stairs, stay there hour after hour listening to him practice. One day I thought I must: must ring his bell. I asked could I take his picture with my box camera. In a way, that was the beginning of this book.”

Well, then, this book. It was intended to preserve the best of Avedon’s already accomplished work, his observations, along with a few of mine. A final selection of photographs seemed impossible, first because Avedon’s portfolio was too richly stocked, secondly because he kept burdening the problem of subtraction by incessantly thinking he must: must hurry off to ring the doorbell of latter-day Rachmaninoffs, persons of interest to him who had by farfetched mishap evaded his ubiquitous lens. Perhaps that implies a connective theme as regards the choice of personalities here included, some private laurel-awarding system based upon esteem for the subject’s ability or beauty; but no, in that sense the selection is arbitrary, on the whole the common thread is only that these are some of the people Avedon happens to have photographed, and about whom he has, according to his calculations, made valid comment.

However, he does appear to be attracted over and again by the mere condition of a face. It will be noticed, for it isn’t avoidable, how often he emphasizes the elderly; and, even among the just middle-aged, unrelentingly tracks down every hard-earned crow’s-foot. In consequence there have been occasional accusations of malice. But, “Youth never moves me,” Avedon explains. “I seldom see anything very beautiful in a young face. I do, though: in the downward curve of Maugham’s lips. In Isak Dinesen’s hands.

So much has been written there, there is so much to be read, if one could only read. I feel most of the people in this book are earthly saints. Because they are obsessed. Obsessed with work of one sort or another. To dance, to be beautiful, tell stories, solve riddles, perform in the street. Zavattini’s mouth and Escudero’s eyes, the smile of Marie-Louise Bousquet: they are sermons on bravado.”

One afternoon Avedon asked me to his studio, a place ordinarily humming with hot lights and humid models and harried assistants and haranguing telephones; but that afternoon, a winter Sunday, it was a spare and white and peaceful asylum, quiet as the snow-made marks settling like cat’s paws on the skylight.

Avedon was in his stocking-feet, wading through a shiny surf of faces, a few laughing and fairly afire with fun and devil-may-care, others straining to communicate the thunder of their interior selves, their art, their inhuman handsomeness, or faces plainly mankindish, or forsaken, or insane: a surfeit of countenances that collided with one’s vision and rather stunned it. Like immense playing cards, the faces were placed in rows that spread and filled the studio’s vast floor.

It was the final collection of photographs for the book; and as we gingerly paraded through this orchard of prunings, warily walked up and down the rows (always, as though the persons underfoot were capable of crying out, careful not to step on a cheek or squash a nose), Avedon said: “Sometimes I think all my pictures are just pictures of me. My concern is, how would you say, well, the human predicament; only what I consider the human predicament may be simply my own.”

He cupped his chin, his gaze darting from Dr. Oppenheimer to Father Darcy: “I hate cameras. They interfere, they’re always in the way. I wish: if I just could work with my eyes alone!” Presently he pointed to three prints of the same photograph, a portrait of Louis Armstrong, and asked which I preferred; to me they were triplets until he demonstrated their differences, indicated how one was a degree darker than the other, while from the third a shadow had been removed. “To get a satisfactory print,” he said, his voice tight with that intensity perfectionism induces, “one that contains all you intended, is very often more difficult and dangerous than the sitting itself.

When I’m photographing, I immediately know when I’ve got the image I really want. But to get the image out of the camera and into the open is another matter. I make as many as sixty prints of a picture, would make a hundred if it would mean a fraction’s improvement, help show the invisible visible, the inside outside.”

We came to the end of the last row, stopped, surveyed the gleaming field of black and white, a harvest fifteen years on the vine. Avedon shrugged. “That’s all. That’s it. The visual symbols of what I want to tell are in these faces. At least,” he added, beginning a genuine frown, the visual symbol of a nature too, in a fortunate sense, vain, too unrequited and questing to ever experience authentic satisfaction, “at least I hope so.”

JOHN HUSTON

Of course, at their best, movies are anti-literature and, as a medium, belong not to writers, not to actors, but to directors, some of whom, to be sure—for one, John Huston—served their apprenticeship as studio scribblers. Huston has said: “I became a director because I couldn’t watch any longer how my work as a writer was ruined.” Though that could not have been the only reason: this lanky, drawling dandy, who might be a cowboy as imagined by Aubrey Beardsley, has in abundance that desire to command Zavattini disavows.

Huston’s work and the manner of man he happens to be are inseparably related, his films silhouette the contours of his private mindscape (as do Eisenstein’s, Ingmar Bergman’s, Jean Vigo’s) in a way not usual to the profession, movies being, the majority of them, objective operations unrevealing of their maker’s subjective preoccupations; therefore it is perhaps permissible to mention in personal style Huston’s stylized person—his riverboat-gambler’s suavity overlaid with roughneck buffooning, the hearty mirthless laughter that rises toward but never reaches his warmly crinkled and ungentle eyes, eyes bored as sunbathing lizards; the determined seduction of his confidential gazes and man’s man camaraderie, all intended as much for his own benefit as that of his audience, to camouflage a refrigerated void of active feeling, for, as is true of every classic seducer, or charmer if you prefer, the success of the seduction depends upon