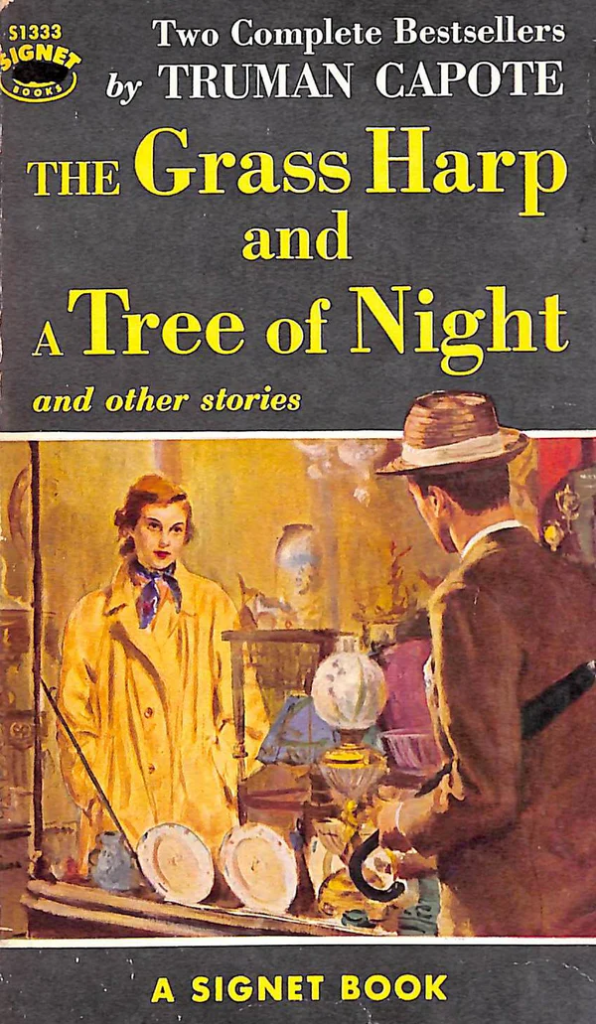

The Grass Harp and A Tree of Night and Other Stories, Truman Capote

The Grass Harp

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

A Tree of Night and other stories

Master Misery

Children on Their Birthdays

Shut a Final Door

Jug of Silver

Miriam

The Headless Hawk

My Side of the Matter

A Tree of Night

The Grass Harp

I

WHEN WAS IT THAT FIRST I heard of the grass harp? Long before the autumn we lived in the China tree; an earlier autumn, then; and of course it was Dolly who told me, no one else would have known to call it that, a grass harp.

If on leaving town you take the church road you soon will pass a glaring hill of bonewhite slabs and brown burnt flowers: this is the Baptist cemetery. Our people, Talbos, Fenwicks, are buried there; my mother lies next to my father, and the graves of kinfolk, twenty or more, are around them like the prone roots of a stony tree. Below the hill grows a field of high Indian grass that changes color with the seasons: go to see it in the fall, late September, when it has gone red as sunset, when scarlet shadows like firelight breeze over it and the autumn winds strum on its dry leaves sighing human music, a harp of voices.

Beyond the field begins the darkness of River Woods. It must have been on one of those September days when we were there in the woods gathering roots that Dolly said: Do you hear? that is the grass harp, always telling a story—it knows the stories of all the people on the hill, of all the people who ever lived, and when we are dead it will tell ours, too.

After my mother died, my father, a traveling man, sent me to live with his cousins, Verena and Dolly Talbo, two unmarried ladies who were sisters. Before that, I’d not ever been allowed into their house.

For reasons no one ever got quite clear, Verena and my father did not speak. Probably Papa asked Verena to lend him some money, and she refused; or perhaps she did make the loan, and he never returned it. You can be sure that the trouble was over money, because nothing else would have mattered to them so much, especially Verena, who was the richest person in town. The drugstore, the drygoods store, a filling station, a grocery, an office building, all this was hers, and the earning of it had not made her an easy woman.

Anyway, Papa said he would never set foot inside her house. He told such terrible things about the Talbo ladies. One of the stories he spread, that Verena was a morphodyte, has never stopped going around, and the ridicule he heaped on Miss Dolly Talbo was too much even for my mother: she told him he ought to be ashamed, mocking anyone so gentle and harmless.

I think they were very much in love, my mother and father. She used to cry every time he went away to sell his frigidaires. He married her when she was sixteen; she did not live to be thirty. The afternoon she died Papa, calling her name, tore off all his clothes and ran out naked into the yard.

It was the day after the funeral that Verena came to the house. I remember the terror of watching her move up the walk, a whip-thin, handsome woman with shingled peppersalt hair, black, rather virile eyebrows and a dainty cheekmole. She opened the front door and walked right into the house. Since the funeral, Papa had been breaking things, not with fury, but quietly, thoroughly: he would amble into the parlor, pick up a china figure, muse over it a moment, then throw it against the wall. The floor and stairs were littered with cracked glass, scattered silverware; a ripped nightgown, one of my mother’s, hung over the banister.

Verena’s eyes flicked over the debris. “Eugene, I want a word with you,” she said in that hearty, coldly exalted voice, and Papa answered: “Yes, sit down, Verena. I thought you would come.”

That afternoon Dolly’s friend Catherine Creek came over and packed my clothes, and Papa drove me to the impressive, shadowy house on Talbo Lane. As I was getting out of the car he tried to hug me, but I was scared of him and wriggled out of his arms. I’m sorry now that we did not hug each other. Because a few days later, on his way up to Mobile, his car skidded and fell fifty feet into the Gulf. When I saw him again there were silver dollars weighting down his eyes.

Except to remark that I was small for my age, a runt, no one had ever paid any attention to me; but now people pointed me out, and said wasn’t it sad? that poor little Collin Fenwick! I tried to look pitiful because I knew it pleased people: every man in town must have treated me to a Dixie Cup or a box of Crackerjack, and at school I got good grades for the first time. So it was a long while before I calmed down enough to notice Dolly Talbo.

And when I did I fell in love.

Imagine what it must have been for her when first I came to the house, a loud and prying boy of eleven. She skittered at the sound of my footsteps or, if there was no avoiding me, folded like the petals of shy-lady fern. She was one of those people who can disguise themselves as an object in the room, a shadow in the corner, whose presence is a delicate happening.

She wore the quietest shoes, plain virginal dresses with hems that touched her ankles. Though older than her sister, she seemed someone who, like myself, Verena had adopted. Pulled and guided by the gravity of Verena’s planet, we rotated separately in the outer spaces of the house.

In the attic, a slipshod museum spookily peopled with old display dummies from Verena’s drygoods store, there were many loose boards, and by inching these I could look down into almost any room. Dolly’s room, unlike the rest of the house, which bulged with fat dour furniture, contained only a bed, a bureau, a chair: a nun might have lived there, except for one fact: the walls, everything was painted an outlandish pink, even the floor was this color.

Whenever I spied on Dolly, she usually was to be seen doing one of two things: she was standing in front of a mirror snipping with a pair of garden shears her yellow and white, already brief hair; either that, or she was writing in pencil on a pad of coarse Kress paper.

She kept wetting the pencil on the tip of her tongue, and sometimes she spoke aloud a sentence as she put it down: Do not touch sweet foods like candy and salt will kill you for certain. Now I’ll tell you, she was writing letters. But at first this correspondence was a puzzle to me.

After all, her only friend was Catherine Creek, she saw no one else and she never left the house, except once a week when she and Catherine went to River Woods where they gathered the ingredients of a dropsy remedy Dolly brewed and bottled. Later I discovered she had customers for this medicine throughout the state, and it was to them that her many letters were addressed.

Verena’s room, connecting with Dolly’s by a passage, was rigged up like an office. There was a rolltop desk, a library of ledgers, filing cabinets. After supper, wearing a green eyeshade, she would sit at her desk totaling figures and turning the pages of her ledgers until even the street-lamps had gone out. Though on diplomatic, political terms with many people, Verena had no close friends at all. Men were afraid of her, and she herself seemed to be afraid of women.

Some years before she had been greatly attached to a blonde jolly girl called Maudie Laura Murphy, who worked for a bit in the post office here and who finally married a liquor salesman from St. Louis. Verena had been very bitter over this and said publicly that the man was no account. It was therefore a surprise when, as a wedding present, she gave the couple a honeymoon trip to the Grand Canyon. Maudie and her husband never came back; they opened a filling station nearby Grand Canyon, and from time to time sent Verena Kodak snapshots of themselves.

These pictures were a pleasure and a grief. There were nights when she never opened her ledgers, but sat with her forehead leaning in her hands, and the pictures spread on the desk. After she had put them away, she would pace around the room with the lights turned off, and presently there would come a hurt rusty crying sound as though she’d tripped and fallen in the dark.

That part of the attic from which I could have looked down into the kitchen was fortified against me, for it was stacked with trunks like bales of cotton. At that time it was the kitchen I most wanted to spy upon; this was the real living room of the house, and Dolly spent most of the day there chatting with her friend Catherine Creek. As a child, an orphan, Catherine Creek had been hired out to Mr. Uriah Talbo, and they had all grown up together, she and the Talbo sisters, there on the old farm that has since become a railroad depot.

Dolly she called Dollyheart, but Verena she called That One. She lived in the