To Europe, Truman Capote

To EUROPE

Standing very still you could hear a harp. We climbed the wall, and there, among the burning rain-drenched flowers of the castle’s garden, sat four mysterious figures, a young man who thumbed a hand harp and three rusted old men who were dressed in patched-together black: how stark they were against the storm-green air. And they were eating figs, those Italian figs so fat the juice ran out of their mouths. At the garden’s edge lay the marble shore of Lago di Garda, its waters swarming in the wind, and I knew then I would be always afraid to swim there, for, like distortions beyond the beauty of ivy-glass, Gothic creatures must move in the depths of water so ominously clear. One of the old men tossed too far a fig peel, and a trio of swans, thus disturbed, rustled the reeds of the waterway.

D. jumped off the wall and gestured for me to join him; but I couldn’t, not quite then: because suddenly it was true and I wanted the trueness of it to last a moment longer—I could never feel it so absolutely again, even the movement of a leaf and it would be lost, precisely as a cough would forever ruin Tourel’s high note. And what was this truth? Only the truth of justification: a castle, swans and a boy with a harp, for all the world out of a childhood storybook—before the prince has entered or the witch has cast her spell.

It was right that I had gone to Europe, if only because I could look again with wonder. Past certain ages or certain wisdoms it is very difficult to look with wonder; it is best done when one is a child; after that, and if you are lucky, you will find a bridge of childhood and walk across it. Going to Europe was like that. It was a bridge of childhood, one that led over the seas and through the forests straight into my imagination’s earliest landscapes. One way or another I had gone to a good many places, from Mexico to Maine—and then to think I had to go all the way to Europe to go back to my hometown, my fire and room where stories and legends seemed always to live beyond the limits of our town. And that is where the legends were: in the harp, the castle, the rustling of the swans.

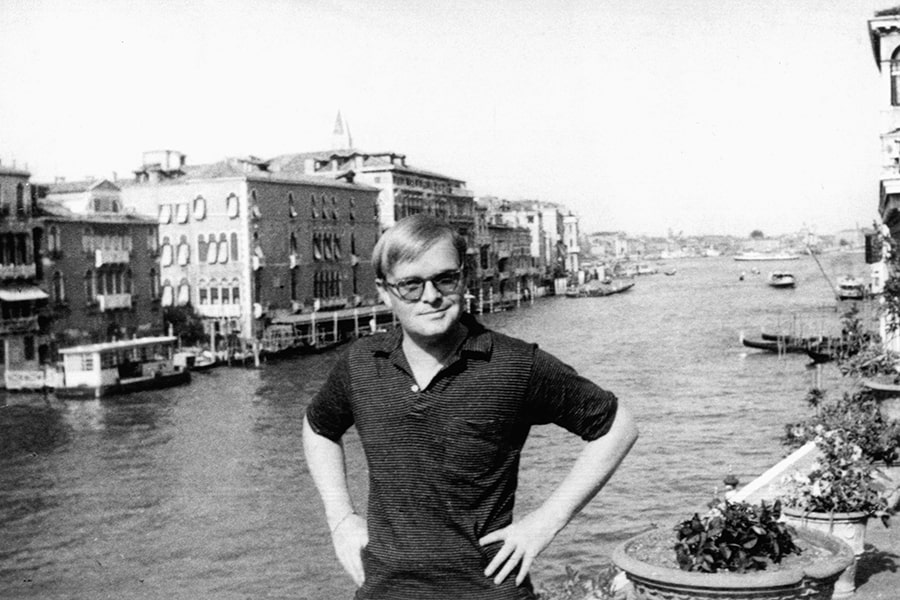

A rather mad bus ride that day had brought us from Venice to Sirmione, an enchanted, infinitesimal village on the tip of a peninsula jutting into Lago di Garda, bluest, saddest, most silent, most beautiful of Italian lakes. Had it not been for the gruesome circumstance of Lucia, I doubt that we should have left Venice. I was perfectly happy there, except of course that it is incredibly noisy: not ordinary city noise, but ceaseless argument of human voices, scudding oars, running feet. It was once suggested that Oscar Wilde retire there from the world. “And become a monument for tourists?” he asked.

It was an excellent advice, however, and others than Oscar have taken it: in the palazzos along the Grand Canal there are colonies of persons who haven’t shown themselves publicly in a number of decades. Most intriguing of these was a Swedish countess whose servants fetched fruit for her in a black gondola trimmed with silver bells; their tinkling made a music atmospheric but eerie.

Still, Lucia so persecuted us we were forced to flee. A muscular girl, exceptionally tall for an Italian and smelling always of wretched condiment oils, she was the leader of a band of juvenile gangsters, displaced roaming youths who had flocked north for the Venetian season. They could be delightful, some of them, even though they sold cigarettes that contained more hay than tobacco, even though they would short-circuit you on a currency exchange. The business with Lucia began one day in the Piazza San Marco.

She came up and asked us for a cigarette; whereupon D., whose heart doesn’t know that we are off the gold standard, gave her a whole package of Chesterfields. Never were two people more completely adopted. Which at first was quite pleasant; Lucia shadowed us wherever we went, abundantly giving us the benefits of her wisdom and protection. But there were frequent embarrassments; for one thing, we were always being turned out of the more elegant shops because of her overwrought haggling with the proprietors; then, too, she was so excessively jealous that it was impossible for us to have any contact with anyone else whatever: we chanced once to meet in the piazza a harmless and respectable young woman who had been with us in the carriage from Milan. “Attention!” said Lucia in that hoarse voice of hers. “Attention!” and proceeded almost to persuade us that this was a lady of infamous past and shameless future. On another occasion D. gave one of her cohorts a dollar watch which he had much admired. Lucia was furious; the next time we saw her she had the watch suspended on a cord around her neck, and it was said the young man had left overnight for Trieste.

Lucia had a habit of appearing in our hotel at any hour that pleased her (she lived no place that we could divine); scarcely sixteen, she would sit herself down, drain a whole bottle of Strega, smoke all the cigarettes she could lay hold of, then fall into an exhausted sleep; only when she slept did her face resemble a child’s. But then one dreadful day the hotel manager stopped her in the lobby and told her that she could no longer visit our rooms. It was, he said, an insupportable scandal. So Lucia, rounding up a dozen of her more brutish companions, laid such siege to the hotel that it was necessary to bring down iron shutters over the doors and call the carabinieri. After that we did our best to avoid her.

But to avoid anyone in Venice is much the same as playing hide-and-seek in a one-room apartment, for there was never a city more compactly composed. It is like a museum with carnivalesque overtones, a vast palace that seems to have no doors, all things connected, one leading into another. Over and over in a day the same faces repeat like prepositions in a long sentence: turn a corner, and there was Lucia, the dollar watch dangling between her breasts. She was so in love with D. But presently she turned on us with that intensity of the wounded; perhaps we deserved it, but it was unendurable: like clouds of gnats her gang would trail us across the piazza spitting invective; if we sat down for a drink, they would gather in the dark beyond the table and shout outrageous jokes.

Half the time we didn’t know what they were saying, though it was apparent that everyone else did. Lucia herself did not overtly contribute to this persecution; she remained aloof, directing her operations at a distance. So at last we decided to leave Venice. Lucia knew this. Her spies were everywhere. The morning we left it was raining; just as our gondola slipped into the water, a little crazy-eyed boy appeared and threw at us a bundle wrapped in newspaper.

D. pulled the paper apart. Inside there was a dead yellow cat, and around its throat there was tied the dollar watch. It gave you a feeling of endless falling. And then suddenly we saw her, Lucia; she was standing alone on one of the little canal bridges, and she was so far hunched over the railing it looked as if she were going to fall. “Perdonami,” she cried, “ma t’amo” (forgive me, but I love you).

In London a young artist said to me, “How wonderful it must be for an American traveling in Europe the first time; you can never be a part of it, so none of the pain is yours, you will never have to endure it—yes, for you there is only the beauty.”

Not understanding what he meant, I resented this; but later, after some months in France and Italy, I saw that he was right: I was not a part of Europe, I never would be. Safe, I could leave when I wanted to, and for me there was only the honeyed, hallowed air of beauty. But it was not so wonderful as the young man had imagined; it was desperate to feel that one could never be a part of moments so moving, that always one would be isolated from this landscape and these people; and then gradually I realized I did not have to be a part of it: rather, it could be a part of me.

The sudden garden, opera night, wild children snatching flowers and running up a darkening street, a wreath for the dead and nuns in noon light, music from the piazza, a Paris pianola and fireworks on La Grande Nuit, the heart-shaking surprise of mountain visions and water views (lakes like green wine in the chalice of volcanoes, the Mediterranean flickering at the bottoms of cliffs), forsaken far-off towers falling in twilight and candles igniting the jeweled corpse of St. Zeno of Verona—all a part of me, elements for the making of my own perspective.

When we left Sirmione, D. returned to Rome and I went back to Paris. Mine was a curious journey. First off, I’d engaged through a dizzy Italian ticket agent a wagonlit aboard the Orient Express, but when I reached Milan, I discovered the arrangement had been