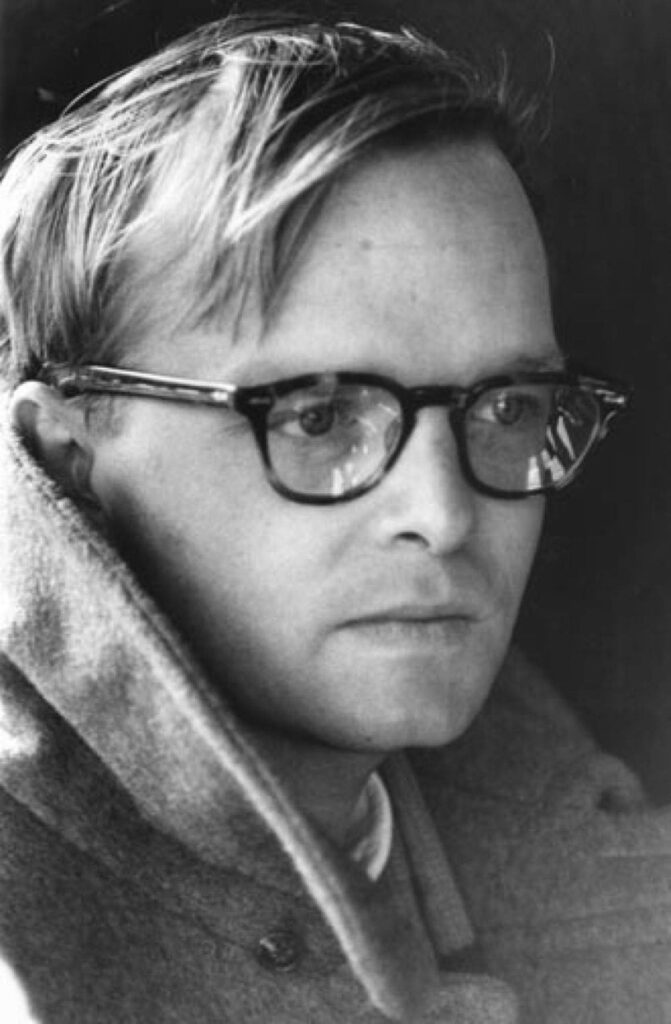

Traffic West, Truman Capote

Traffic West

Four chairs and a table. On the table, paper—in the chairs, men. Windows above the street. On the street, people—against the windows, rain.

This were, perhaps, an abstraction, a painted picture only, but that the people, innocent, unsuspecting, moved below, and the rain fell wet on the window.

For the men stirred not, the legal, precise document, on the table moved not. Then—

“Gentlemen, our four interests have been brought together, checked, and harmonized. Each one’s actions now should to his own particulars be bent. And so I make a suggestion that we signify consent, attach our names hereto, and part.”

A man rose, a paper in his hands. Another rose. He took the paper, scanned, and spoke.

“This satisfies our needs; we drew it well. Indeed, our companies are by this piece assured advantage and security. Yes, in this document I read great profit. I’ll sign.”

A third arose. He fixed his lens, perused the scroll. His lips in silence moved, and when words sounded, each was weighed.

“We must admit—our lawyers, too, agree—the text and wording of this note is clear. I have it from advice on every hand: herein is, despite the power it assumes, what legally can be, what by the law is. Thus, I’ll sign.” He read the script anew, and passed it to the fourth.

An executive like the others, he fain would have affixed his name and gone. But his brow clouded. He sat, reading, scanning, examining. Then he laid the paper down.

“I cannot, though agreeing, sign the document. Nor can you.” He saw their startled faces. “It is the power of the thing that damns it.

The very reasons you have just given, that show the lawful measures it allows. The purposes of huge extent, the full assurance of support, the mighty steps permitted these things, though lawful, are not for us.

If unlawful, we could risk it, for the law would then be acting contrary—supporting, not oppressing, the thousands of workers; protecting, not destroying, the interests of weaker peoples.

“But if the law, our government, allows we have the right to make this tract to move, through legal pen, ten thousands for what our interests want—and worse, to misuse those same ones whose rights we represent; then we must draw the line—reject a measure which risks the welfare of the many in our care.

“We have power, as do all who serve great interests.

But if we judge by God, a thing most difficult for moneyed minds to do, we sense, as men of might, our duty to the ‘average man,’ and, gentlemen, I beg you, take no such selfish action.”

Again the room was still. A businessman had just torn down one kind of code, and in this tearing down revealed another.

Three others saw his reasoning, and, having seen, replaced old business goals with goals of brotherhood.

“Let us take the bus away from here, and leave the document destroyed in legal fashion.”

The bright morning sun streaked over rows of waiting roofs and struck against the closely drawn blinds of the house on the hill.

The covers on a huge, medieval bed stirred and a sleepy head turned on the pillow as a knock sounded on the door.

Two freshly shaven, trim young men filed into the room.

“Good morning, Uncle. Your orange juice,” greeted one as his brother stepped to the windows and raised the blinds. The eager sun thus welcomed streamed into the room.

“You’re late, Gregory,” growled the man in bed. He sipped his juice, then raised himself. “And damn it! If Minnie leaves seeds in this drink once more, I’ll get rid of her.” He spat the seed on the rug.

“Pick it up, Henry, and throw it in the wastebasket,” he commanded.

“Uncle,” grinned Gregory as he returned from the receptacle. “How’s your leg? We’ve good news—”

“Shut up,” the older man rasped.

“When I tell Henry to do something, I want Henry to do it. You may be twins but I can tell you apart. So, Gregory, pick that seed out of the wastebasket and let Henry do as I said.

“All my life I’ve seen to it that things were just so. I’ve kept my library exactly the same way. I’ve kept my room exactly the same way.

I’ve kept the house the same way. I’ve gone to town and worked. I’ve gone to church and prayed—exactly the same way. I’ve thought and acted as I should have. My great strength as mayor has not been in myself but in my sound habits—”

“Oh, you’ll be elected again, Uncle,” cheered one. “But right now, we’ve good news for you—”

“Hell, boy, of course I’ll be elected!” interrupted the invalid. “I’m not talking about that. He signaled impatiently for an extra pillow. “My greatest worry is you two. Your dead father wanted me to take care of you. But God, what can I do?

I break my leg—it’ll have to come off, you know. I send for you two to be in my office until I recover. Hell! It’s one thing to lose a leg, but it’s too much to lose an election because of someone else’s stupidity. And, say, did you touch that cross word puzzle on the floor?…Good, I’ve got to have some relaxation.”

“We’ve good, news, Uncle—”

But he had sunk back in his covers. His rage was abating. He noticed sunshine playing on the top of his bed. “Listen to me first.” His voice was sad.

“I’ve lived a good life.” He turned to them. “But I’ve never had any fun. Not a bit. Being too busy to marry. I’ve left women quite alone. I didn’t smoke, or drink, or sw— Hell.

I could swear, but it’s no fun. And I never enjoyed golf, couldn’t break ninety. Never liked music, either—or poetry, or—” He thought of his cross word puzzle. He became silent, remained silent….His mind followed a strange course, one it had never taken before.

The sun was saying “hello” to his face now.

“By Jove, boys!” he cried, “I’ve never looked at it that way! Politics is one big cross word puzzle—delightful. And”—he sat bolt upright—“so is life! Aaaaaaa!”

He had never smiled like this. “Last night, Henry, I thought I might make something of myself, if I only had two legs. But now, lame or not, I see I can be just like—just like”—he glanced around the room—“Yes! just like the sun!”

He pointed a trembling, happy finger at the ball of fire.

“Our uncle!” laughed the twins, and Henry said, “Your legs are your own. That is the good news!

The doctor has declared the amputation unnecessary. You should begin walking as soon as possible. Tomorrow afternoon the three of us will take the bus to town!”

A ten-inch record whirled on the turntable. From a small speaker issued a beautiful, stirring trumpet solo.

The girl rose from the bench on which she had been seated. She reached for the switch and the high trumpet tones died away in a gurgling gasp.

The music had disturbed her; she was dreaming of her childhood.

Outside the little try-out room, row upon row of record albums hemmed in two men. One pulled out a Beethoven quartet and handed it to the other.

“You can try this out, sir, as soon as the young woman is through with the machine.”

“No need,” laughed the other. “I think I can trust the Budapest String Quartet without hearing them.” The girl appeared from the booth and laid fifty-five cents on the counter.

“I’ll take it,” she said, holding up the disc. And so, man and girl left the Music Shop, records under their arms.

“It’s a warm day,” she began.

“Oh,” he replied, “the day holds nothing for me. Nor does the night anymore.”

“Do you feel that way, too?” she returned quickly. “Do you feel that—that you’re like an engine on a track—just going you don’t know where?” She turned red—he was a stranger after all. “But I’m serious, do you see any point in living?”

“I have no night; I have no day,” he replied sincerely. “I really have only one thing.” He held up his album. “My very life hangs on music.”

He turned to the girl. He saw that she was pretty, but it was more her charm than her face.

With a friendly motion, he put his hand in hers. “Are you going through the park?”

“I can,” she replied, and they stepped along the pathway. A minute later they came upon a wooden bench between two trees.

“I always stop here for a spell,” he said, loosening her hand. “Perhaps we’ll meet again.”

The color mounted on her cheeks. She trembled slightly and, touching his coat with one hand, whispered. “Do you mind if I sit with you? Oh please! I must!” She stood silent.

He bit his lips, gently took her record, and, placing it on the bench with his album, pulled her down beside him. A moment later he drew her closer, then, slowly, placed one arm behind her.

“I was afraid to hope it,” he murmured, “for from the moment I first saw you, I knew why music meant so much to me.

It was sort of a substitute—a glorious substitute, for something finer—for something—something”—he looked at her—“like you.”

They sat there, each thrilled by the other.

“The earth spins round us now like one huge record,” he went on. “This record plays—hear, listen, see—it is the song of life!

“Now, music is everywhere. These trees, this grass, this sky, swing to our rhythm.” He stretched out one arm. “Oh love!” He bent down and kissed her.

“Tomorrow afternoon we’ll take the bus, and go to town for a license, and the rest.”

“Yes,” she sang, fixing his