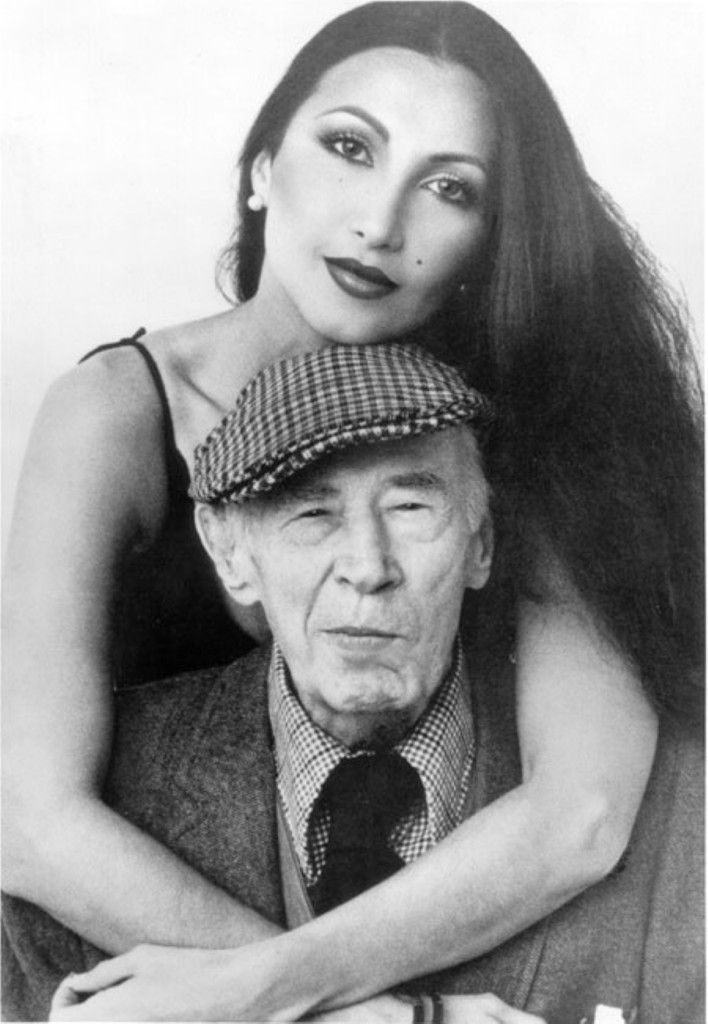

Benno, The Wild Man from Borneo, Henry Miller

Benno, The Wild Man from Borneo

BENNO HAS ALWAYS reminded me of a Sandwich Islander.

Not only that his hair is by turns straight and kinky, not only that he rolls his eyes in delirious wrath, not only that he is gaunt and cannibalistic, positively ferocious when his breadbasket is empty, but that he is also gentle and peaceful as a dove, calm, placid, cool as a volcanic lake.

He says he was born in the heart of London, of Russian parents, but that is a myth he has invented to conceal his truly fabulous origin.

Anyone who has ever skirted an archipelago knows the uncanny faculty which the islands have of appearing and disappearing. Unlike the mirages of the desert these mysterious islands do truly disappear from sight, do truly bob up from the unknown depths of the sea.

Benno is very much like that. He inhabits an archipelago of his own in which there are these mysterious apparitions and disparitions.

Nobody has ever explored Benno with any thoroughness. He is elusive, slippery, treacherous, volatile, uncanny. Sometimes he is a mountain peak covered with bright snow, sometimes a broad glacial lake, sometimes a volcano spouting fire and brimstone.

Sometimes he rolls quietly down to the ocean front and lies there like a big white Easter egg waiting to be dipped and packed away in a softly padded basket.

And sometimes he gives the impression of one who was not born of a mother’s womb, but of a monster who picked his way out of a hard-boiled egg.

If you examine him closely you will see that he has rudimentary claws like the mock turtle, that he has spurs like the clover cock, and if you examine very closely you will discover that, like the dodo bird, he carries a harmonica in his right tubercle.

At an early age, a very early age, he found himself living the lonely, desperate life of a river pirate on a little island off Hell Gate. Near by was an ancient whirlpool, such as Homer speaks of in the Carthaginian version of the Odyssey.

Here he perfected himself in that culinary art which was to stand him in good stead during his uninterrupted privations. Here he acquired a knowledge of Chinese, Turkestani, Kurd and the less well-known dialects of Upper Rhodesia.

Here also he learned to write in that hand which only the prophets of the desert have mastered, an illegible hand which is nevertheless intelligible to students of esoteric lore.

Here too he gleaned an inkling of those strange Runic patterns which he was later to employ in his pink and orange gouaches, his linoleum fretworks, his arboreal hallucinations.

Here he studied the seed and the ovum, the unicellular life of the animalculae which daily filled his lobster-pots. Here the mystery of the egg first engrossed him—not only its shape and balance, but its logic, its ordained irreversibility.

Over and over again the egg crops up, sometimes in a china blue dream, sometimes counterpointed against the tripod, sometimes chipped and nascent.

Exhausted by ceaseless exploration and investigation Benno is forever returning to the source and fundament, the center of his own vital creation: the egg.

Always it is an Easter egg, which is to say a holy egg. Always the lost racial egg, seed of pride and strength, which has perdured since the destruction of the holy temple.

When there is nothing left but despair Benno curls up inside his holy egg and goes to sleep. He sleeps the long schizophrenic sleep of the winter season.

It is more congenial than running about looking for sirloin steaks and chopped onions. When he gets unbearably hungry he will eat his egg, and then for a time he sleeps anywhere, often right outside the Closerie des Lilas, beside the statue erected in memory of Marshal Ney.

These are the Waterloo sleeps, so to speak, when all is rain and mud—and Blücher never appears. When the sun comes out Benno appears again—alive, chipper, perky, sardonic, irritable, buzzing, questioning, dubious, querulous, suspicious, effervescent, always in blue overalls and sleeves rolled up, always a quid of tobacco in the corner of his mouth. By sundown he has made a dozen new canvases, large and small. Whereupon it is a question of space, of frames, of nails and thumb-tacks.

The cobwebs are shaken down, the floor washed, the ladder removed. The bed is left stranded in the middle air, the lice make merry, the cowbells ring.

Nothing to do but to stroll out to Parc Montsouris. Here, denuded of flesh and raiment, deserted by human kind, Benno studies the tom-tit and the amarillo, makes note of the weather-cocks, tests the sand and gravel which his kidneys are constantly throwing out.

With Benno it is always a feast or a famine. Either he is loading crushed rock on the Hudson or he is painting the side of a house.

He is a dynamo, a gravel-crusher, a lawn-mower, an eight-day clock all in one. Now and then he lies up for repairs; the barnacles are scraped off and all seams dried and caulked. Sometimes a new poop-deck is installed.

You look at his progeny and it is Easter Island by the Count Potocki de Montalk: new landmarks, new monuments, new relics, all slithering in a Camembert green light which comes up out of the bulrushes.

There he is, Benno, sitting in the midst of his archipelago, and the eggs running about like mad. Only new eggs this time, with new equilibrium, all frolicking on the greensward. Benno, fat and lazy, lolls in the sun with the gravy running down his chops. He reads last year’s newspapers to while away the time.

He invents new dishes made of sea-weed and scallops, or failing scallops, mountain oysters. All with a dash of Worcestershire sauce and fried parsley. At such moments he loves everything that is succulent and bunting with juice. He tears the bones apart and growls like a contented wolf. He ruts.

As I say, all to conceal his fabulous origin. To conceal his monstrous birth Benno goes about smooth of tongue, sleek as a puma after the rains, talking now of this thing, now of that.

Inside him there is an unholy abracadabra fermenting. Strange equations form, queer plant-like growths, fungus, toadstools, marshmallow, poison ivy, the mandrake, the eucalyptus, all forming inside him in the hollow of the entrails in a sort of wild linoleum pattern which the burin will trace when he comes out of his trance.

There are at least nine different cities buried beneath his midriff; the middle one is Samarkand where he had a rendezvous once with death.

Here he passed through a glazing process which left the middle layers smooth and minor-like. Here, when he is in utter desperation, he strolls among the stalagmites and stalactites, cool as a knife and garnished with mulberry leaves.

Here he sees himself ever young, the Swiss Family Robinson kill-joy, the Gloomy Gus who played by Hell Gate’s shores. Here the nostalgic odors are revived, the smell of the mud-crab and the sea turtle, all the tender little delicacies of the old island life when his palate was being formed.

Like the bed louse and the amaranthus Benno makes progress in all directions at once. At twelve he was a virtuoso; at sixty he will be fresh and dandy, a bright young bantam with a red comb and featherweight gloves, to say nothing of the spurs.

Circular progress, but no speed and no errors. Between enthusiasms he dips like the leviathan to snooze on the ocean floor; or, like the sea-cow, he will come up to graze along the Labrador Coast.

Now and then he flies from wall to wall—with the close-clipped wings which he invents during hibernation. Occasionally he grows a coat of fast Merino wool fresh from the Oberammergau region.

In his right moments he trusts nobody. He was born with the evil eye, the acetylene torch planted in the middle of his forehead. When he is restive he champs and paws at the bit; when he is full of oats he kicks up his heels; when he is angry he snorts fire.

Usually he is gentle and placid, still as the Hibernian in his fen. He loves the green meadows and the high hills, the kites soaring over Soo-chow, the gibbet and the rack; he loves the leather-heeled coolies, the oyster pirates, the wardens of Dannemora and the patient carpenter with his adze and footrule. Trigonometry he loves also and the intricate flights of the homing pigeon, or the fortifications of the Dardanelles.

He loves everything that is complicated by rule and logarithm or spiced with fiery tinctures: he loves the styptic poisons, the triple bromides, the touch of carborundum, the glaze of mercurochrome.

He loves light and space as well as champagne and oysters. But best of all he loves a rumpus, because then the wild man of Borneo comes out and the sky is full of prickly heat. In anger he will bite his own tail or bray like the donkey. In anger he is apt to cut off his own fetlocks.

His anger comes up out of the groin, like jets of prussic acid. It puts a clean coat of varnish over his work, his loves, his friendships.

It is the heraldic emblem, the tarantula which you will find embroidered on all his nightshirts, on his socks and even his cuff-buttons. Bright, feathery anger which he wears like a plume. It becomes him like an emolument, or an emulsion.

Such is Benno, as I have always known him and found him to be. A sturdy cutlass