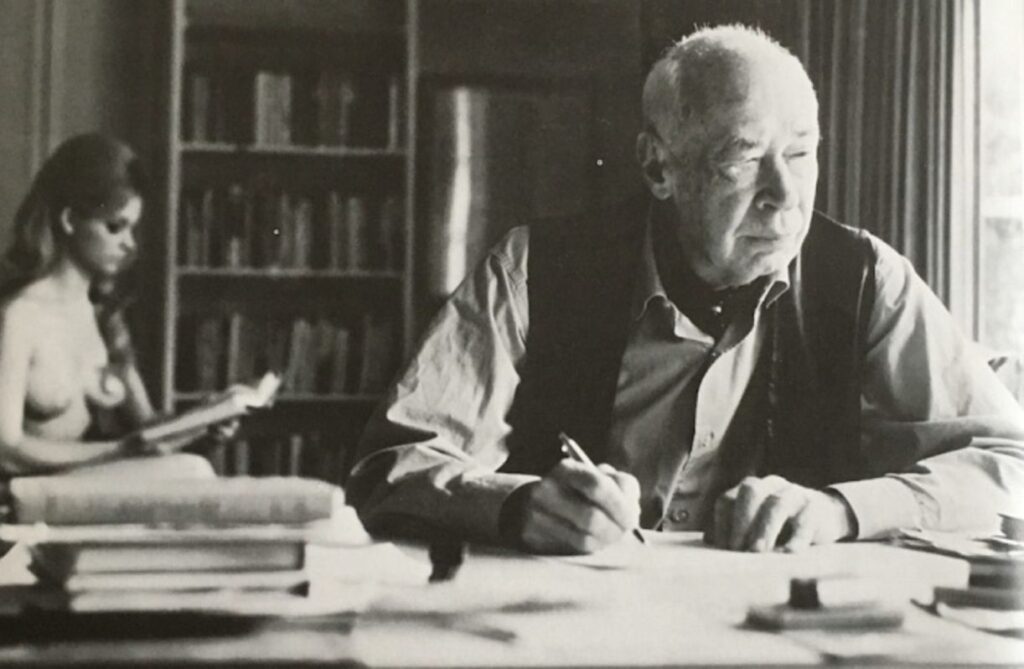

Into the Future, Henry Miller

Into the Future

TO APPROACH the world of Lawrence two things must be steadily borne in mind: first, the nature of his individual temperament, and second, the relation between such a temperament and the times.

For Lawrence was both distinctively unique and at the same time a figure representative of our time.

He stands out among the constellations as a tiny, blazing star; he glows more brilliantly in the measure that we understand our age.

Had he not reflected his epoch so thoroughly he would have already been forgotten.

As it is, his importance increases with time. It is not that he grows bigger, or that he moves nearer the earth.

No, he remains where he was at the beginning: he remains just a tiny bit above the horizon, like an evening star, but as night comes on, and it is the night which is coming on stronger and stronger, he waxes more brilliant. We understand him better as we go down into the night.

Before me lie the notes from which this book on Lawrence will emerge. They make a huge, baffling pile. Some of them I don’t understand myself any more. Some of them I see already in a new light.

The notes are full of contradictions. Lawrence was full of contradictions. Life itself is full of contradictions.

I want to impose no higher order upon the man, his works, his thought, than life imposes. I do not want to stand outside life, judging it, but in it, submitting to it, reverencing it.

I speak of contradictions. And immediately I feel impelled to contradict this. For example, I wish to make it clear at the outset that a man like Lawrence was right, right in everything he said, in everything he did, even when what he said or did was obviously wrong, obviously stupid, obviously prejudiced or unjust. (He is at his very best, to illustrate what I mean, in such writing as the studies on Poe and on Melville.)

Lawrence was opposed to the world as is. The world is wrong, always was wrong, always will be wrong. In this sense Lawrence was right, is still right, and always will be right.

Every sensitive being aware of his own power, his own right, senses this opposition. The world however is there and will not be denied. The world says NO. The world is eternally wagging its head NO.

The most important figure for the entire Western world has been for two thousand years the man who was the quintessence of contradictoriness: Christ. He was a contradiction to himself and to the world.

And yet those who were opposed to him, or to the world, or to themselves, have understood. He is understood by all everywhere, even though denied. Is it because he was a contradiction? Let us not answer this immediately. Let us leave this question in suspense. . . .

Here, touching on this point, we stand very close to something which concerns us all vitally. We are approaching the enigma from behind, as it were. Let us think a moment calmly. There was Christ, the one splendid shining figure who has dominated our whole history.

There was also another man—St. Francis of Assisi. He was second to Christ in every sense. He made a tremendous impression upon our world—perhaps because, like those Bodhisattvas who renounced Nirvana in order to aid humanity, he too elected to remain close to us. There were these two resplendent figures, then.

Will there be a third? Can there be? If there was any man in the course of modern times who most nearly attained this summit it was D. H. Lawrence. But the tragedy of Lawrence’s life, the tragedy of our time, is this—that had he been this third great figure we would never know it.

The man was never fully born—because he was never squarely opposed. He is a bust perpetually bogged in a quagmire. Eventually the bust will disappear altogether. Lawrence will go down with the time which he so magnificently represented.

He knew it, too. That is why the hope and the despair which he voiced are so finely equilibrated. Consummatum est, he cried out towards the last. Not on his death-bed, but on the cross, while alive and in full possession of his faculties.

Just as Christ knew in advance what was in store for him, accepting his role, so too Lawrence knew and accepted. Each went to a different fate. Christ had already performed his work when he was led to the cross.

Lawrence nailed himself to the cross because he knew that the task could not be performed—neither his own task nor the world’s. Jesus was killed off. Lawrence was obliged to commit suicide. That is the difference.

Lawrence was not the first. There were others before him, all through the modern period, who had been doing themselves in. Each suicide was a challenge. Rimbaud, Nietzsche—these tragedies almost brought about a spark. Lawrence goes out and nothing happens. He sells better, that is about all.

I said a moment ago that the contradictoriness of Christ brought us very close to something vital, a fear which has us in the bowels. Lawrence made us again aware of it—though it was almost instantly dismissed. What is the essence of this enigma?

To be in the world and not of it. To deepen the conception of the role of man. How is this done? By denying the world and proclaiming the inner reality? By conquering the world and destroying the inner reality? Either way there is defeat. Either way there is triumph, if you like. They are the same, defeat and victory—it is only a question of changing one’s position.

There is the world of outer reality, or action, and the world of inner reality, or thought.* The fulcrum is art. After long use, after endless see-saws, the fulcrum wears itself away. Then, as though divinely appointed, there spring up lone, tragic figures, men who offer their own bare backs as fulcrum for the world.

They perish under the overwhelming burden. Others spring up, more and more of them, until out of many heroic sacrifices there is built up a fulcrum of living flesh which can balance the weight of the world again. This fulcrum is art, which at first was raw flesh, which was action, which was faith, which was the sense of destiny.

Today the world of action is exhausted, and also the world of thought. There is neither an historical sense nor an inner, metaphysical reality. No one man today can get down and offer his bare back as support.

The world has spread itself out so thin that the mightiest back would not be broad enough to support it. Today it is dawning on men that if they would find salvation they must lift themselves up by their own bootstraps. They must discover for themselves a new sense of equilibrium.

Each one for himself must recover the sense of destiny. In the past a figure like Christ could create an imaginary world powerful enough in its reality to make him the lever of the world. Today there are millions of sacrificial scapegoats but not enough power in the lot of them to raise a grain of sand. The world is out of whack and men individually are out of whack.

We are on the wrong track, all of us. One group, the larger one, insists on changing the external pattern—the social, political, economic configuration. Another group, very small but increasing in power, insists on discovering a new reality.

There is no hope either way. The inner and outer are one. If now they are divorced it is because a new way of life is about to be ushered in. There is only one realm in which inner and outer may still be fused and that is the realm of art.

Most art will reflect the death which is taking place, but only the most forward spirits can give an intimation of the life which is to come. Just as primitive peoples carry on in our midst their life of fifty or a hundred thousand years ago, so the artists.

We are facing an absolutely new condition of life. An entirely new cosmos must be created, and it must be created out of our separate, isolate, living parts. It is we, the indestructible morsels of living flesh, who make up the cosmos. The cosmos is not made up in the mind, by philosophers and metaphysicians, nor is it made by God.

An economic revolution will certainly not create it. It is something we carry within us and which we build up about us: we are part of it and it is we who must bring it into being. We must realize who and what we are. We must carry through to the finish, both in creation and destruction. What we do most of the time is either to deny or to wish.

Ever since the beginning of our history, our Western history, we have been willing the world to be something other than it is. We have been transmogrifying ourselves in order to adapt ourselves to an image which has been a mirage.

This will has come to exhaustion in supreme doubt. We are paralyzed; we whirl about on the pivot of self like drunken dervishes. Nothing will liberate us but a new knowledge—not the Socratic wisdom, but realization, which is knowledge become active.

For, as Lawrence predicted, we are entering the era of the Holy Ghost. We are about to give up the ghost of our dead self and enter a new domain. God is dead. The Son is dead. And we are dead only