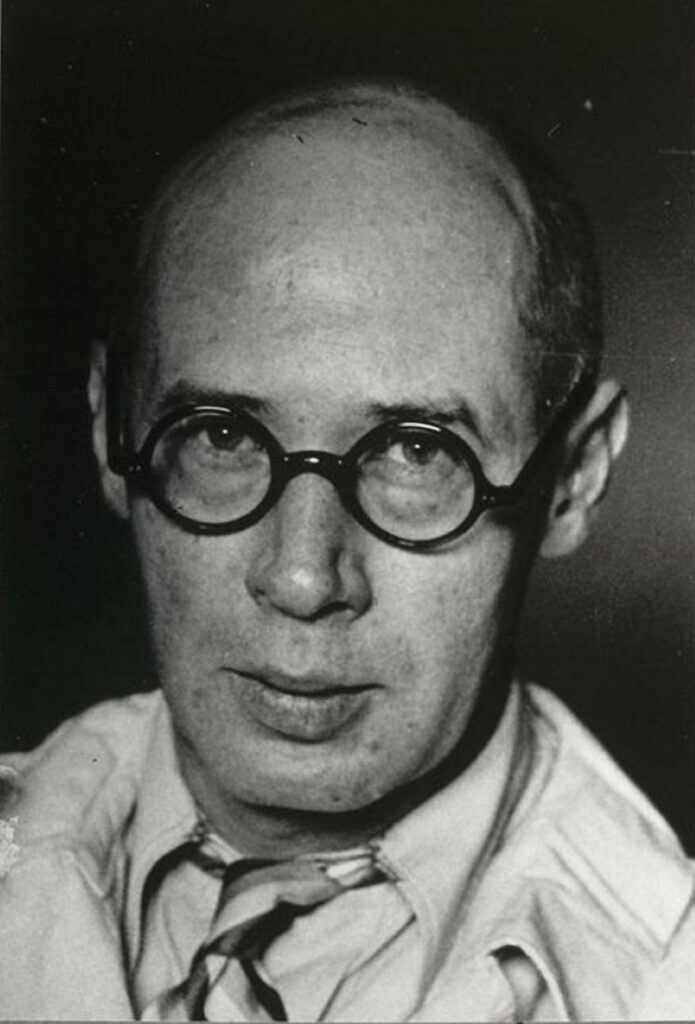

Seraphita, Henry Miller

Seraphita

IT HAS BEEN SAID that February 28, 1832, was probably the most important date in Balzac’s life. It was the day that he received his first letter from Madame Hanska, the woman whom after seventeen years of courtship he was to marry, just four months before his death.

From his twenty-first to his twenty-ninth year Balzac wrote forty volumes under various pseudonyms.

After the colossal failure of his publishing venture he suddenly came to himself and, resuming the role of writer, which he had thought to drop in order to gain more experience of life, he began to sign his own name to his work.

Having tapped the true source of inspiration, he was so overwhelmed with ideas and literary projects that for a couple of years he was scarcely able to cope with his energies.

It was a repetition of that singular state—“congestion de lumière,” to use his own expression—which he had experienced when he was returned to his parents by the masters of the College of Vendôme in his fifteenth year; only this time he was paralyzed by the multiplicity of outlets open to him, and not by the struggle to assimilate what he had imbibed.

His whole career as a writer, indeed, was a Promethean drama of restitution. Balzac was not only tremendously receptive, as highly sensitized as a photographic plate, but he was also gifted with an extraordinary intuition.

He read faces as easily as he read books, and in addition he possessed, as it is said, “every memory.” His was a protean nature, opulent, jovial, expansive, yet also chaste, reserved and secretive.

For the extraordinary endowments with which Nature had blessed him he was obliged to pay the penalty of submission. He looked upon himself as a spiritual “exile.”

It was a supreme task for him to coordinate his faculties, to establish order out of the chaos which his superabundant nature was constantly creating.

His physiological flair was an expression of this obsessive passion “to establish order,” for then as now Europe was in the throes of dissolution.

His boast to finish with the pen what Napoleon had begun with the sword signified a deep desire to reveal the significance of the true relationships existing in the world of human society. It was Cuvier rather than Napoleon whom he took as a model.

From the time of his financial set-back, from 1827 to 1836, in short, Balzac lived a life which was in many ways reminiscent of Dostoievski’s lifelong bondage. Indeed, it is during this very period that, in order to stave off his creditors, Dostoievski undertook the translation of Eugenie Grandet.

Through excessive suffering and deprivation both Dostoievski and Balzac, destined to become the foremost novelists of the nineteenth century, were permitted to give us glimpses of worlds which no other novelists have yet touched upon, or even imagined.

Enslaved by their own passions, chained to the earth by the strongest desires, they nevertheless revealed through their tortured creations the evidences of worlds unseen, unknown, except, as Balzac says, “to those loftier spirits open to faith who can discern Jacob’s mystical stair.” Both of them believed in the dawn of a new world, though frequently accused, by their contemporaries, of being morbid, cynical, pessimistic and immoral.

I am not a devotee of Balzac. For me the Human Comedy is of minor importance. I prefer that other comedy which has been labeled “divine,” in testimony doubtless of our sublime incorrigibility.

But without a knowledge of Seraphita, the subject of this essay—possibly also Louis Lambert—there can be no real understanding of Balzac’s life and work. It is the cornerstone of the grand edifice.

Seraphita is situated symbolically at the dawn of a new century. “Outside,” says Balzac at the end, “the first summer of the nineteenth century was in all its glory.”

Outside, please notice. For Seraphita was conceived in the womb of a new day which only now, a hundred years later, is beginning to make itself clear.

It was in the midst of the most harassed period of his life, in the year 1830, that Balzac took up quarters in the Rue Cassini, “midway,” as he says, “between the Carmelites and the place where they guillotine.”

Here were begun the truly herculean labors for which he is celebrated and which undoubtedly cut his life in half, for with anything like a normal rhythm he would have lived a hundred or more.

To give some idea of his activities at this period let me state briefly that in 1830 he is credited with seventy publications, in 1831 with seventy-five. Writing to his publisher, Werdet, in 1835, he says: “There is not a single other writer who has done this year what I have done . . . anyone else would have died.”

He cites the seven books he has just finished, as well as the political articles he wrote for the Chronique de Paris. The important thing to note, however, is that one of the seven books he refers to was the most unusual book of his whole career, probably one of the most unique books in all literature: Seraphita. How long the actual writing of it took is not known; the first installment of it appeared June 1, 1834, in the Revue de Paris.

It appeared, together with Louis Lambert and The Exiles, in book form in December, 1835, the volume itself entitled Le Livre Mystique. The critics, judging it from the three installments of Seraphita which had appeared in the review, condemned it as “an unintelligible work.” However, the first edition of the book was exhausted in ten days, and the second a month later. “Not such bad fortune for an unintelligible work,” Balzac remarked.

Seraphita was written expressly for Madame Hanska with whom, after the receipt of her first letter, he maintained a lifelong correspondence.

It was during a trip to Geneva that the book was conceived, and in December of 1833, just three months after his meeting with Madame Hanska, it was begun. It was intended, in Balzac’s own words, “to be a masterpiece such as the world has never seen.”

And this it is, despite all its faults, despite the prophecies of the critics, despite the apparent neglect and obloquy into which it has fallen. Balzac himself never doubted its value or uniqueness, as he sometimes did in the case of his other works.

Though subsequently included in La Comédie Humaine, it really forms part of the Études Philosophiques. In the dedication to Madame Hanska he speaks of it “as one of those balustrades, carved by some artist full of faith, on which the pilgrim leans to meditate on the end of man. . . .” The seven divisions of the book undoubtedly have an occult structure and significance.

As narrative it is broken by disquisitions and expositions which, in a lesser work, would be fatal. Inwardly regarded, which is the only way it can be looked at, it is a model of perfection. Balzac said everything he had to say, with swiftness, precision and eloquence. To me it is the style of the last quartets of Beethoven, the will triumphant in its submission.

I accept the book implicitly as a mystical work of the highest order. I know that, if obviously it seems to have been inspired by Swedenborg’s work, it was also enriched by other influences, among them Jacob Boehme, Paracelsus, Ste. Therèse, Claude Saint-Martin, and so on.

As a writer, I know that a book such as this could not have been written without the aid of a higher being: the reach of it, the blinding lucidity, the wisdom, not man’s certainly, the force and the eloquence of it, betray all the qualities of a work dictated if not by God then by the angels.

The book is, in fact, about an angel in human guise, a being neither male nor female, or rather now one now the other, and yet always more, “not a being,” as one of the characters remarks, “but a whole creation.”

In any case, whether Seraphita or Seraphitus, whether, as the author states, “her sex would have puzzled the most learned man to pronounce on,” the subject of this book is a being, a being filled with light, whose behavior may baffle the blundering minds of the critics but never the earnest reader.

Those who know what the book is about will share the sentiment of that young student in Vienna who is reported to have accosted Balzac in the street and begged permission to kiss the hand that wrote Seraphita.

The events related are almost as simple and brief as those of Christ’s own life. As with that other drama, the hierarchical order of events works contrariwise to the historical, clock-time movement.

The adumbration is tremendous; time is stopped, and in the awesome, all-enveloping silence which shrouds the mysterious being called Seraphita, one can actually hear the growth of those wings which will carry her aloft to that world of which Balzac was aware ever since the Angel visited him as a boy at the College of Vendôme.

The story is symbolic and revelatory from beginning to end. It is not limited, as is Louis Lambert, to what I might call the intellectual aspect of occultism, but proceeds straight from the heart which Balzac knew to be the true, vital center of man’s being. It is a Rosicrucian drama pure and simple. It is about Love, the triumph of Love over Desire.

And who better qualified than Balzac to give us the dramatic recital of this conflict? Had he not himself confessed somewhere that if ever he should conquer over desire he would die of grief?

On the highest level of creative imagination, spiritually