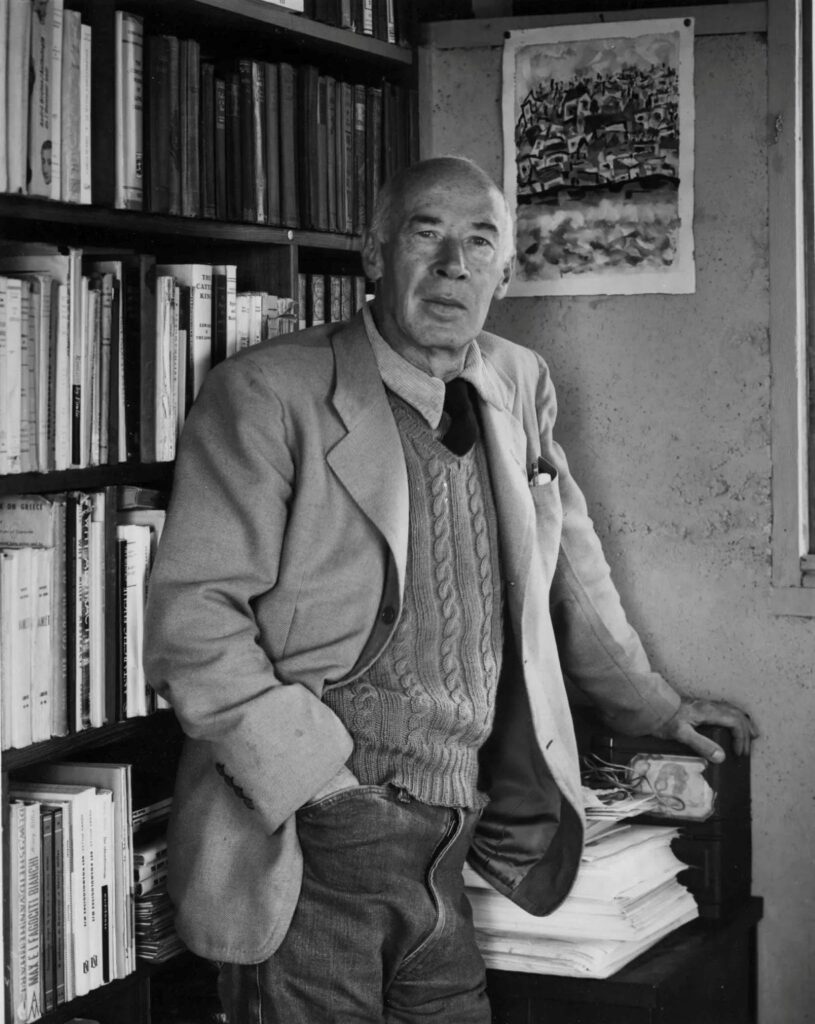

The Alcoholic Veteran with the Washboard Cranium, Henry Miller

The Alcoholic Veteran with the Washboard Cranium

IN TULSA not long ago I saw a shorty short movie called “The Happiest Man on Earth.” It was in the O. Henry style but the implications were devastating. How a picture like that could be shown in the heart of the oil fields is beyond my comprehension.

At any rate it reminded me of an actual human figure whom I encountered some weeks previously in New Orleans. He too was trying to pretend that he was the happiest mortal alive.

It was about midnight and my friend Rattner and I were returning to our hotel after a jaunt through the French Quarter. As we were passing the St. Charles Hotel a man without a hat or overcoat fell into step with us and began talking about the eyeglasses he had just lost at the bar.

“It’s hell to be without your glasses,” he said, “especially when you’re just getting over a jag. I envy you fellows. Some fool drunk in there just knocked mine off and stepped on them. Just sent a telegram to my oculist in Denver—suppose I’ll have to wait a few days before they arrive.

I’m just getting over one hell of a binge: it must have lasted a week or more, I don’t know what day it is or what’s happened in the world since I fell off the wagon. I just stepped out to get a breath of air—and some food. I never eat when I’m on a bat—the alcohol keeps me going.

There’s nothing to do about it, of course; I’m a confirmed alcoholic. Incurable. I know all about the subject—studied medicine before I took up law. I’ve tried all the cures, read all the theories. . . .

Why look here—” and he reached into his breast pocket and extricated a mass of papers along with a thick wallet which fell to the ground—“look at this, here’s an article on the subject I wrote myself. Funny, what? It was just published recently in. . .” (he mentioned a well-known publication with a huge circulation).

I stooped down to pick up the wallet and the calling cards which had fluttered out and fallen into the gutter. He was holding the loose bundle of letters and documents in one hand and gesticulating eloquently with the other.

He seemed to be utterly unconcerned about losing any of his papers or even about the contents of the wallet. He was raving about the ignorance and stupidity of the medical profession. They were a bunch of quacks; they were hijackers; they were criminal-minded. And so on.

It was cold and rainy and we, who were bundled up in overcoats, were urging him to get moving.

“Oh, don’t worry about that,” he said, with a good-natured grin, “I never catch cold. I must have left my hat and coat in the bar. The air feels good,” and he threw his coat open wide as if to let the mean, penetrating night wind percolate through the thin covering in which he was wrapped.

He ran his fingers through his shock of curly blond hair and wiped the corners of his mouth with a soiled handkerchief. He was a man of good stature with a rather weather-beaten face, a man who evidently lived an outdoor life.

The most distinctive thing about him was his smile—the warmest, frankest, most ingratiating smile I’ve ever seen on a man’s face. His gestures were jerky and trembly, which was only natural considering the state of his nerves.

He was all fire and energy, like a man who has just had a shot in the arm. He talked well, too, exceedingly well, as though he might have been a journalist as well as doctor and lawyer. And he was very obviously not trying to make a touch.

When we had walked a block or so he stopped in front of a cheap eating house and invited us to step in with him and have something to eat or drink. We told him we were on our way home, that we were tired and eager to get to bed.

“But only for a few minutes,” he said. “I’m just going to have a quick bite.”

Again we tried to beg off. But he persisted, taking us by the arm and leading us to the door of the café. I repeated that I was going home but suggested to Rattner that he might stay if he liked. I started to disengage myself from his grasp.

“Look,” he said, suddenly putting on a grave air, “you’ve got to do me this little favor. I’ve got to talk to you people. I might do something desperate if you don’t. I’m asking you as a human kindness—you wouldn’t refuse to give a man a little time, would you, when you knew that it meant so much to him?”

With that of course we surrendered without a word. “We’re in for it now,” I thought to myself, feeling a little disgusted with myself for letting myself be tricked by a sentimental drunkard.

“What are you going to have?” he said, ordering himself a plate of ham and beans which, before he had even brought it to the table, he sprinkled liberally with ketchup and chili sauce. As he was about to remove it from the counter he turned to the server and ordered him to get another plate of ham and beans ready.

“I can eat three or four of these in a row,” he explained, “when I begin to sober up.” We had ordered coffee for ourselves. Rattner was about to take the checks when our friend reached for them and stuck them in his pocket. “This is on me,” he said, “I invited you in here.”

We tried to protest but he silenced us by saying, between huge gulps which he washed down with black coffee, that money was one of the things that never bothered him.

“I don’t know how much I’ve got on me now,” he continued. “Enough for this anyway. I gave my car to a dealer yesterday to sell for me. I drove down here from Idaho with some old cronies from the bench—they were on a jamboree.

I used to be in the legislature once,” and he mentioned some Western State where he had served. “I can ride back free on the railroad,” he added. “I have a pass. I used to be somebody once upon a time. . . .” He interrupted himself to go to the counter and get another helping.

As he sat down again, while dousing the beans with ketchup and chili sauce, he reached with his left hand into his breast pockct and dumped the whole contents of his pocket on the table. “You’re an artist, aren’t you?” he said to Rattner. “And you’re a writer, I can tell that,” he said, looking at me.

“You don’t have to tell me, I sized you both up immediately.” He was pushing the papers about as he spoke, still energetically shoveling down his food, and apparently poking about for some articles which he had written and which he wanted to show us. “I write a bit myself,” he said, “whenever I need a little extra change.

You see, as soon as I get my allowance I go on a bat. Well, when I come out of it I sit down and write some crap for”—and here he mentioned some of the leading magazines, those with the big circulation. “I can always make a few hundred dollars that way, if I want to. There’s nothing to it.

I don’t say it’s literature, of course. But who wants literature? Now where in the hell is that story I wrote about a psychopathic case . . . I just wanted to show you that I know what I’m talking about. You see. . . .” He broke off suddenly and gave us a rather wry, twisted smile, as though it were hopeless to try to put it all in words.

He had a forkful of beans which he was about to shovel down. He dropped the fork, like an automaton, the beans spilling all over his soiled letters and documents, and leaning over the table he startled me by seizing my arm and placing my hand on his skull, rubbing it roughly back and forth.

“Feel that?” he said, with a queer gleam in his eye. “Just like a washboard, eh?” I pulled my hand away as quickly as I could. The feel of that corrugated brainpan gave me the creeps. “That’s just one item,” he said.

And with that he rolled up his sleeve and showed us a jagged wound that ran from the wrist to the elbow. Then he pulled up the leg of his trousers. More horrible wounds. As if that were not enough he stood up quickly, pulled off his coat and, quite as if there were no one but just us three in the place, he opened his shirt and displayed even uglier scars.

As he was putting on his coat he looked boldly around and in clear, ringing tones he sang with terrible bitter mockery “America, I love you!” Just the opening phrase. Then he sat down as abruptly as he had gotten up and quietly proceeded to finish the ham and beans.

I thought there would be a commotion but no, people continued eating and talking just as before, only now we had become the center of attention. The man at the cash register seemed rather nervous and thoroughly undecided as to what to do. I wondered what next.

I half expected our friend to raise his voice and begin