Invitation to a Beheading, Vladimir Nabokov

Contents

Foreword

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Foreword

The Russian original of this novel is entitled Priglashenie na kazn′. Notwithstanding the unpleasant duplication of the suffix, I would have suggested rendering it as Invitation to an Execution; but, on the other hand, Priglashenie na otsechenie golovï (“Invitation to a Decapitation”) was what I really would have said in my mother tongue, had I not been stopped by a similar stutter.

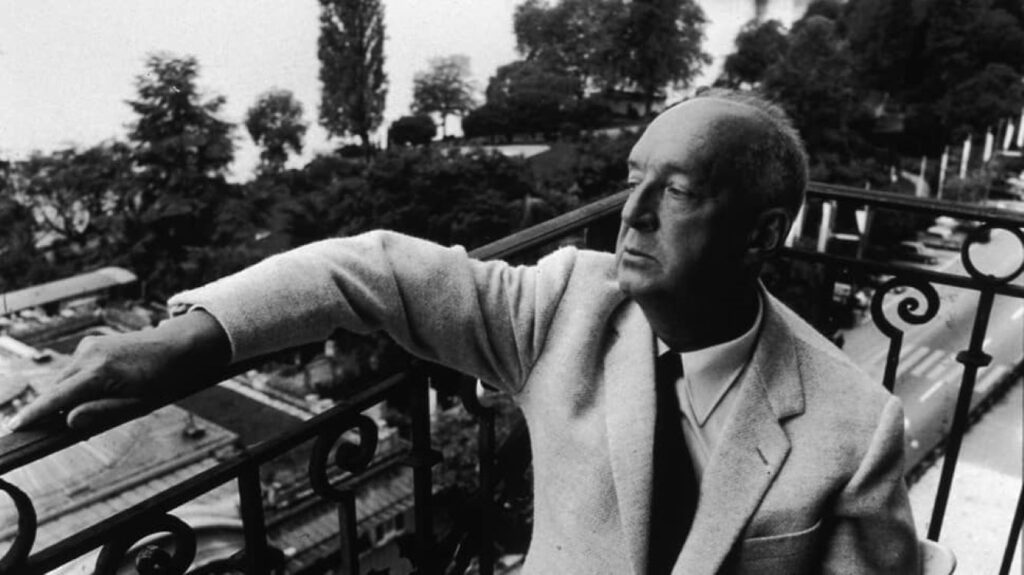

I composed the Russian original exactly a quarter of a century ago in Berlin, some fifteen years after escaping from the Bolshevist regime, and just before the Nazi regime reached its full volume of welcome. The question whether or not my seeing both in terms of one dull beastly farce had any effect on this book, should concern the good reader as little as it does me.

Priglashenie na kazn′ came out serially in a Russian émigré magazine, the Sovremennïya Zapiski, appearing in Paris, and later, in 1938, was published in that city by the Dom Knigi. Emigré reviewers, who were puzzled but liked it, thought they distinguished in it a “Kafkaesque” strain, not knowing that I had no German, was completely ignorant of modern German literature, and had not yet read any French or English translations of Kafka’s works. No doubt, there do exist certain stylistic links between this book and, say, my earlier stories (or my later Bend Sinister); but there are none between it and Le chateau or The Trial. Spiritual affinities have no place in my concept of literary criticism, but if I did have to choose a kindred soul, it would certainly be that great artist rather than G. H. Orwell or other popular purveyors of illustrated ideas and publicistic fiction. Incidentally, I could never understand why every book of mine invariably sends reviewers scurrying in search of more or less celebrated names for the purpose of passionate comparison. During the last three decades they have hurled at me (to list but a few of these harmless missiles) Gogol, Tolstoevski, Joyce, Voltaire, Sade, Stendhal, Balzac, Byron, Bierbohm, Proust, Kleist, Makar Marinski, Mary McCarthy, Meredith (!), Cervantes, Charlie Chaplin, Baroness Murasaki, Pushkin, Ruskin, and even Sebastian Knight. One author, however, has never been mentioned in this connection—the only author whom I must gratefully recognize as an influence upon me at the time of writing this book; namely, the melancholy, extravagant, wise, witty, magical, and altogether delightful Pierre Delalande, whom I invented.

If some day I make a dictionary of definitions wanting single words to head them, a cherished entry will be “To abridge, expand, or otherwise alter or cause to be altered, for the sake of belated improvement, one’s own writings in translation.” Generally speaking the urge to do this grows in proportion to the length of time separating the model from the mimic; but when my son gave me to check the translation of this book and when I, after many years, had to reread the Russian original, I found with relief that there was no devil of creative emendation for me to fight.

My Russian idiom, in 1935, had embodied a certain vision in the precise terms that fitted it, and the only corrections which its transformation into English could profit by were routine ones, for the sake of that clarity which in English seems to require less elaborate electric fixtures than in Russian. My son proved to be a marvelously congenial translator, and it was settled between us that fidelity to one’s author comes first, no matter how bizarre the result. Vive le pédant, and down with the simpletons who think that all is well if the “spirit” is rendered (while the words go away by themselves on a naïve and vulgar spree—in the suburbs of Moscow for instance—and Shakespeare is again reduced to play the king’s ghost).

My favorite author (1768–1849) once said of a novel now utterly forgotten “Il a tout pour tous. Il fait rire l’enfant et frissonner la femme. Il donne à l’homme du monde un vertige salutaire et fait rêver ceux qui ne rêvent jamais.” Invitation to a Beheading can claim nothing of the kind. It is a violin in a void. The worldling will deem it a trick. Old men will hurriedly turn from it to regional romances and the lives of public figures. No clubwoman will thrill. The evil-minded will perceive in little Emmie a sister of little Lolita, and the disciples of the Viennese witch-doctor will snigger over it in their grotesque world of communal guilt and progresivnoe education. But (as the author of Discours sur les ombres said in reference to another lamplight): I know (je connais) a few (quelques) readers who will jump up, ruffling their hair.

Oak Creek Canyon, Arizona

June 25, 1959

Comme un fou se croit dieu,

nous nous croyons mortels.

—Delaland: Discours sur les ombres

Chapter One

In accordance with the law the death sentence was announced to Cincinnatus C. in a whisper. All rose, exchanging smiles. The hoary judge put his mouth close to his ear, panted for a moment, made the announcement and slowly moved away, as though ungluing himself. Thereupon Cincinnatus was taken back to the fortress. The road wound around its rocky base and disappeared under the gate like a snake in a crevice. He was calm; however, he had to be supported during the journey through the long corridors, since he planted his feet unsteadily, like a child who has just learned to walk, or as if he were about to fall through like a man who has dreamt that he is walking on water only to have a sudden doubt: but is this possible?

Rodion, the jailer, took a long time to unlock the door of Cincinnatus’ cell—it was the wrong key—and there was the usual fuss. At last the door yielded. Inside, the lawyer was already waiting. He sat on the cot, shoulder-deep in thought, without his dress coat (which had been forgotten on a chair in the courtroom—it was a hot day, a day that was blue all through); he jumped impatiently when the prisoner was brought in. But Cincinnatus was in no mood for talking. Even if the alternative was solitude in this cell, with its peephole like a leak in a boat—he did not care, and asked to be left alone; they all bowed to him and left.

So we are nearing the end. The right-hand, still untasted part of the novel, which, during our delectable reading, we would lightly feel, mechanically testing whether there were still plenty left (and our fingers were always gladdened by the placid, faithful thickness) has suddenly, for no reason at all, become quite meager: a few minutes of quick reading, already downhill, and—O horrible! The heap of cherries, whose mass had seemed to us of such a ruddy and glossy black, had suddenly become discrete drupes: the one over there with the scar is a little rotten, and this one has shriveled and dried up around its stone (and the very last one is inevitably hard and unripe) O horrible! Cincinnatus took off his silk jerkin, put on his dressing gown and, stamping his feet a little to stop the shivering, began walking around the cell.

On the table glistened a clean sheet of paper and, distinctly outlined against this whiteness, lay a beautifully sharpened pencil, as long as the life of any man except Cincinnatus, and with an ebony gleam to each of its six facets. An enlightened descendant of the index finger. Cincinnatus wrote: “In spite of everything I am comparatively. After all I had premonitions, had premonitions of this finale.” Rodion was standing on the other side of the door and peering with a skipper’s stern attention through the peephole.

Cincinnatus felt a chill on the back of his head. He crossed out what he had written and began shading gently; an embryonic embellishment appeared gradually and curled into a ram’s horn. O horrible! Rodion gazed through the blue porthole at the horizon, now rising, now falling. Who was becoming seasick? Cincinnatus. He broke out in a sweat, everything grew dark, and he could feel the rootlet of every hair. A clock struck—four or five times—with the vibrations and re-vibrations, and reverberations proper to a prison. Feet working, a spider—official friend of the jailed—lowered itself on a thread from the ceiling. No one, however, knocked on the wall, since Cincinnatus was as yet the sole prisoner (in such an enormous fortress!).

Sometime later Rodion the jailer came in and offered to dance a waltz with him. Cincinnatus agreed. They began to whirl. The keys on Rodion’s leather belt jangled; he smelled of sweat, tobacco and garlic; he hummed, puffing into his red beard; and his rusty joints creaked (he was not what he used to be, alas—now he was fat and short of breath). The dance carried them into the corridor. Cincinnatus was much smaller than his partner. Cincinnatus was light as a leaf. The wind of the waltz made the tips of his long but thin mustache flutter, and his big limpid eyes looked askance, as is always the case with timorous dancers. He was indeed very small for a full-grown man. Marthe used to say that his shoes were too tight for her. At the bend in the corridor stood another guard, nameless, with a rifle and wearing a doglike mask with a gauze mouthpiece. They described a circle near him and glided back into the cell, and now Cincinnatus regretted that the swoon’s friendly embrace had been