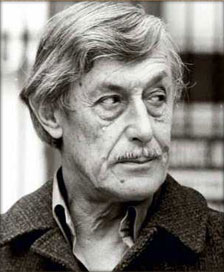

Viktor Platonovich Nekrasov Born June 4 (17), 1911, Kyiv Date of death September 3, 1987, Paris — Russian Soviet writer, dissident and emigrant, laureate of the Stalin Prize of the second degree (1947)

Biography

Viktor Nekrasov was born on June 4 (17), 1911 in Kyiv, in the family of a doctor. Father – Platon Fedoseevich Nekrasov, mother – Zinaida Nikolaevna Nekrasova. The elder brother Kolya Nekrasov was flogged to death as a young man (by Petliurites or the Reds).

In 1936, Viktor Nekrasov graduated from the architectural faculty of the Kyiv Construction Institute (he studied under Iosif Karakis, with whom he maintained close relations for many years), and simultaneously studied at the theater studio at the theater. After graduating from the institute, he worked as an actor and theater artist (in Vyatka, Vladivostok and Rostov-on-Don).

In Rostov, Nekrasov served in the Red Army Theater of the North Caucasus Military District, which performed in military garrisons and army camps. As actress Varvara Shurkhovetskaya, who served in the same theater as Viktor, recalled, after the start of the Great Patriotic War, the actors — despite the exemption they were entitled to — began asking to go to the front; however, out of the entire troupe, only Nekrasov managed to get to the front (he was a sapper by military specialty, and there were not enough of them).

In 1941-1944, Nekrasov was at the front as a regimental engineer and deputy commander of a sapper battalion, participated in the Battle of Stalingrad, and after being wounded in Poland, in early 1945, he was demobilized with the rank of captain. Member of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) since 1944 (expelled from the party in 1973).

The story “In the Trenches of Stalingrad”, published in 1946 in the magazine “Znamya” (1946, No. 8-10), was one of the first books about the war written truthfully, as far as it was possible at that time.

It brought the writer real fame: it was republished in a total circulation of several million copies, translated into 36 languages. For this book, after Joseph Stalin read it, Viktor Nekrasov received the Stalin Prize of the 2nd degree in 1947. Based on the story and Nekrasov’s script, the film “Soldiers” was shot in 1956, which was awarded the All-Union Film Festival Prize (Innokenty Smoktunovsky played one of his first big film roles in this film). The films The City Lights Up (1958) and To the Unknown Soldier (1961) were made based on Viktor Nekrasov’s scripts.

In 1959, Nekrasov wrote the story Kira Georgievna and published a series of articles in the Literary Gazette about the need to perpetuate the memory of Soviet people shot by the Nazis in 1941 in Babi Yar. Nekrasov was accused of organizing “mass Zionist gatherings.” And yet, the monument was erected in Babi Yar, and the writer deserves considerable credit for this.

After V. P. Nekrasov’s essay The House of the Turbins was published in Novy Mir (1967, No. 8), people began to flock to this house. The house is not named after the author of the novel “The White Guard”, Mikhail Bulgakov, who lived here, but after the names of his heroes who “lived” here. The house has become a modern legend of Andreevsky Descent.

In 1966, he signed a letter of 25 cultural and scientific figures to the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee L. I. Brezhnev against the rehabilitation of Stalin.

In the 1960s, he visited Italy, the USA and France. The writer described his impressions in essays, for which he was accused of “groveling before the West” in Melor Sturua’s devastating article “A Tourist with a Cane”. Due to his liberal statements, he received a party reprimand in 1969, and on May 21, 1973, at a meeting of the Kyiv City Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, he was expelled from the CPSU. During a search of Nekrasov’s home on January 17, 1974 in Kyiv, the KGB confiscated all of his manuscripts and illegal literature, and over the next six days the writer was subjected to hours-long interrogations. Nekrasov’s last book in the USSR, “In Life and in Letters,” was published in 1971. After that, an unofficial ban was placed on the publication of his new books, and then all of his previously published books began to be confiscated from libraries.

During March-May 1974, several provocations were carried out against Nekrasov: he was detained by the police on the streets of Kyiv and Moscow, allegedly to establish his identity, after which he was released, sometimes with apologies, sometimes without them. On May 20, 1974, Nekrasov wrote a personal letter to Brezhnev, in which, having mentioned all these provocations, he stated: “I have become inconvenient. I don’t know to whom. But I can’t tolerate any more insults. I am forced to take a step that I would never have taken under other circumstances. I want to receive permission to leave the country for a period of two years.” Having received no response, on July 10, 1974, Viktor Nekrasov and his wife Galina Bazii submitted documents to leave the USSR (to visit a relative in Switzerland for three months). On July 28, Nekrasov was informed that his request would be granted, after which he received permission to travel abroad to Lausanne (Switzerland). Nikolai Ulyanov (his uncle) issued a summons to Switzerland for Viktor Nekrasov. On September 12, 1974, with Soviet passports valid for five years, Nekrasov and his wife flew from Kyiv to Zurich.

In Switzerland, Viktor Nekrasov met with Vladimir Nabokov. Then he lived in Paris, first with Maria Rozanova and Andrei Sinyavsky, then in rented apartments. In the summer of 1975, he was invited by the writer Vladimir Maksimov to the post of deputy editor-in-chief of the magazine “Continent” (1975-1982), and collaborated with Anatoly Gladilin in the Paris bureau of Radio Liberty.

After Viktor Nekrasov and Galina Bazii left for abroad, Nekrasov’s stepson (Bazii’s son from his first marriage) Viktor Kondyrev remained in Rostov with his wife and son: he was not given the right to leave. Nekrasov turned to Louis Aragon for help, whom the Soviet leadership was going to award the Order of Friendship of Peoples. He came to the Soviet embassy and declared that he would publicly renounce the order if Kondyrev was not allowed to leave the USSR. This threat worked, and in 1976 Kondyrev and his family were given permission to leave for Paris to his mother and stepfather.

In May 1979, Viktor Nekrasov was deprived of Soviet citizenship “for activities incompatible with the high title of citizen of the USSR.” In his last years, he lived with his wife on Kennedy Square in Vanves (a suburb of Paris), in the same house as Viktor Kondyrev. He was very interested in Gorbachev’s perestroika that had begun in the USSR. The writer’s last work was “A Little Sad Story”.

Viktor Nekrasov died of lung cancer in Paris on September 3, 1987. He was buried in the Sainte-Genevieve-des-Bois cemetery.

Family

Father – Platon Fedoseevich Nekrasov (1878-1917) – bank employee.

Mother – Zinaida Nikolaevna Nekrasova (née Motovilova; June 24, 1879 – October 7, 1970, Kyiv) – phthisiatrician, distant relative of Anna Akhmatova. Leonid Kiselyov’s poem “Autumn City” was dedicated to her

Brother – Nikolai Platonovich Nekrasov (1902-1918)

Grandmother – Alina Antonovna Motovilova (1857-1943)

Grandfather – Nikolai Ivanovich Motovilov (1855-1888)

Aunt – Sofia Nikolaevna Motovilova (1881-1966)

Aunt – Vera Nikolaevna Ulyanova (Motovilova) (1885-1968)

Uncle – Nikolai Alekseevich Ulyanov (1881-1977)

Wife – Galina Viktorovna Bazii (1914-2001)

Stepson – Viktor Leonidovich Kondyrev (born 1939)

Perpetuation of memory

Memorial plaque to V. Nekrasov in Kyiv, Khreshchatyk, 15.

Memorial plaque on Khreshchatyk Street, 15[9] (where Viktor Nekrasov lived from 1950 to 1974, in apartment No. 10)

Library named after Viktor Platonovich Nekrasov – in 1997, the library in Kiev on Yaroslavskaya Street was named after the writer Viktor Platonovich Nekrasov.

In one of the display cases of the Museum of One Street are photographs and autographs of the writer. After his essay “The House of the Turbins”, published in “Novy Mir”, a new life began for this street.

Vladimir Kornilov wrote and dedicated a poem to V. Nekrasov:

Your voice, having built into the muffler,

Climbs out of Tartarus.

Vika, Vika, honor and conscience

After the camp era.

100th anniversary of the writer’s birthday

The Commission on Renaming and Memorial Signs decided to name Davydov Boulevard after Viktor Nekrasov.

Ukrposhta issued a postal envelope with a portrait of V. Nekrasov. (artist Georgy Varkach)

On June 14, 2011, the National Museum of Literature of Ukraine (Kyiv, Bohdan Khmelnytsky Street, 11) hosted an Evening in Memory of Viktor Nekrasov, “All Life in the Trenches,” dedicated to the writer’s 100th anniversary. Among others, Vasily Skuratovsky, Tatyana Rogozovskaya, Yuriy Vilensky, Ilya Levitas, Dmitry Chervinsky and others shared their memories of the famous writer.

On June 17, 2011, the library named after N. A. Dobrolyubov in Nizhny Novgorod held a literary-patriotic hour “He, who defended Stalingrad, is buried in Paris.” On January 18, 2012, the National Museum of Literature of Ukraine (Kiev, B. Khmelnitsky St., 11) hosted an Evening in Memory of the writer and human rights activist Viktor Nekrasov. The organizers were the Ukrainian PEN Club and the M. Bulgakov Literary Memorial Museum. Vladimir Kryzhanovsky, Les Tanyuk, Semyon Gluzman, Yevgeny Sverstyuk, Aleksandr Parnis, Tatyana Rogozovskaya, Yuri Vilensky and others shared their memories and thoughts. The documentary film “All Life in the Trenches” (directed by Elena Yakovich), dedicated to the life and human rights activities of the writer, was shown.

Works in English translation

Kira Georgievna. Tr. Walter N. Vickery, New York, Pantheon Books [1962], 183p.

Front-line Stalingrad. Tr. David Floyd, London, Harvill Press, [1962], 320 p.

The Perch. Tr. Vic Shneerson, in The Third Flare: Three War Stories, Moscow, Foreign Languages Pub. House, [1963], 229p.

Both Sides of the Ocean; a Russian Writer’s Travels in Italy and the United States, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, [1964], xv, 191p.

Postscripts, Tr. Michael G. Falchikov; Quartet Books/Namara Group, London, [1991], 201p.