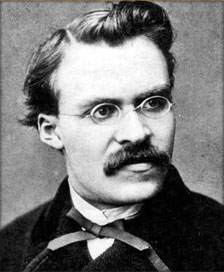

Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None (German: Also sprach Zarathustra: Ein Buch für Alle und Keinen), also translated as Thus Spake Zarathustra, is a work of philosophical fiction written by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche; it was published in four volumes between 1883 and 1885. The protagonist is nominally the historical Zarathustra, more commonly called Zoroaster in the West.

Much of the book consists of discourses by Zarathustra on a wide variety of subjects, most of which end with the refrain “thus spoke Zarathustra”. The character of Zarathustra first appeared in Nietzsche’s earlier book The Gay Science (at §342, which closely resembles §1 of “Zarathustra’s Prologue” in Thus Spoke Zarathustra).

The style of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra has facilitated varied and often incompatible ideas about what Nietzsche’s Zarathustra says. The “xplanations and claims” given by the character of Zarathustra in this work “are almost always analogical and figurative”. Though there is no consensus about what Zarathustra means when he speaks, there is some consensus about that which he speaks. Thus Spoke Zarathustra deals with ideas about the Übermensch, the death of God, the will to power, and eternal recurrence.

Origins

Nietzsche was born into, and largely remained within, the Bildungsbürgertum, a sort of highly cultivated middle class. By the time he was a teenager, he had been writing music and poetry. His aunt Rosalie gave him a biography of Alexander von Humboldt for his 15th birthday, and reading this inspired a love of learning “for its own sake”. The schools he attended, the books he read, and his general milieu fostered and inculcated his interests in Bildung, a concept at least tangential to many in Zarathustra, and he worked extremely hard.

He became an outstanding philologist almost accidentally, and he renounced his ideas about being an artist. As a philologist he became particularly sensitive to the transmissions and modifications of ideas, which also bears relevance into Zarathustra. Nietzsche’s growing distaste toward philology, however, was yoked with his growing taste toward philosophy. As a student, this yoke was his work with Diogenes Laertius. Even with that work he strongly opposed received opinion.

With subsequent and properly philosophical work he continued to oppose received opinion. His books leading up to Zarathustra have been described as nihilistic destruction. Such nihilistic destruction combined with his increasing isolation and the rejection of his marriage proposals (to Lou Andreas-Salomé) devastated him. While he was working on Thus Spoke Zarathustra he was walking very much. The imagery of his walks mingled with his physical and emotional and intellectual pains and his prior decades of hard work. What “erupted” was Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

Nietzsche has said that the central idea of Thus Spoke Zarathustra is the eternal recurrence. He has also said that this central idea first occurred to him in August 1881: he was near a “pyramidal block of stone” while walking through the woods along the shores of Lake Silvaplana in the Upper Engadine, and he made a small note that read “6,000 feet beyond man and time”.

A few weeks after meeting this idea, he paraphrased in a notebook something written by Friedrich von Hellwald about Zarathustra. This paraphrase was developed into the beginning of Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

A year and a half after making that paraphrase, Nietzsche was living in Rapallo. Nietzsche claimed that the entire first part was conceived, and that Zarathustra himself “came over him”, while walking. He was regularly walking “the magnificent road to Zoagli” and “the whole Bay of Santa Margherita”. He said in a letter that the entire first part “was conceived in the course of strenuous hiking: absolute certainty, as if every sentence were being called out to me”.

Nietzsche returned to “the sacred place” in the summer of 1883 and he “found” the second part.

Nietzsche was in Nice the following winter and he “found” the third part.

According to Nietzsche in Ecce Homo it was “scarcely one year for the entire work”, and ten days each part. More broadly, however, he said in a letter: “The whole of Zarathustra is an explosion of forces that have been accumulating for decades”.

In January 1884, Nietzsche finished the third part and thought the book finished. But by November he expected a fourth part to be finished by January. He also mentioned a fifth and sixth part leading to Zarathustra’s death, “or else he will give me no peace”. But after the fourth part was finished he called it “a fourth (and last) part of Zarathustra, a kind of sublime finale, which is not at all meant for the public”.

The first three parts were initially published individually and were first published together in a single volume in 1887. The fourth part was written in 1885. While Nietzsche retained mental capacity and was involved in the publication of his works, forty copies of the fourth part were printed at his own expense and distributed to his closest friends, to whom he expressed “a vehement desire never to have the Fourth Part made public”. In 1889, however, Nietzsche became significantly incapacitated. In March 1892 part four was published separately, and the following July the four parts were published in a single volume.

In the 1888 Ecce , Nietzsche explains what he meant by making the Persian figure of Zoroaster the protagonist of his book:

People have never asked me as they should have done, what the name of Zarathustra precisely meant in my mouth, in the mouth of the first immoralist; for that which distinguishes this Persian from all others in the past is the very fact that he was the exact reverse of an immoralist. Zarathustra was the first to see in the struggle between good and evil the essential wheel in the working of things. The translation of morality into the realm of metaphysics, as force, cause, end-in-itself, is his work. But the very question suggests its own answer.

Zarathustra created this most portentous of all errors,—morality; therefore he must be the first to expose it. Not only because he has had longer and greater experience of the subject than any other thinker,—all history is indeed the experimental refutation of the theory of the so-called moral order of things,—but because of the more important fact that Zarathustra was the most truthful of thinkers. In his teaching alone is truthfulness upheld as the highest virtue—that is to say, as the reverse of the cowardice of the “idealist” who takes to his heels at the sight of reality. Zarathustra has more pluck in his body than all other thinkers put together. To tell the truth and to aim straight: that is the first Persian virtue. Have I made myself clear? … The overcoming of morality by itself, through truthfulness, the moralist’s overcoming of himself in his opposite—in me—that is what the name Zarathustra means in my mouth.

— Ecce Homo, “Why I Am a Fatality”

Thus, “as Nietzsche admits himself, by choosing the name of Zarathustra as the prophet of his philosophy in a poetical idiom, he wanted to pay homage to the original Aryan prophet as a prominent founding figure of the spiritual-moral phase in human history, and reverse his teachings at the same time, according to his fundamental critical views on morality. The original Zoroastrian world-view interpreted being on the basis of the universality of the moral values and saw the whole world as an arena of the struggle between two fundamental moral elements, Good and Evil, depicted in two antagonistic divine figures [Ahura Mazda and Ahriman]. Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, in contrast, puts forward his ontological immoralism and tries to prove and reestablish the primordial innocence of beings by destroying philosophically all moralistic interpretations and evaluations of being”.

Synopsis

First part

The book begins with a prologue that sets up many of the themes that will be explored throughout the work. Zarathustra is introduced as a hermit who has lived ten years on a mountain with his two companions, an eagle and a serpent. One morning – inspired by the sun, which is happy only when it shines upon others – Zarathustra decides to return to the world and share his wisdom. Upon descending the mountain, he encounters a saint living in a forest, who spends his days praising God. Zarathustra marvels that the saint has not yet heard that “God is dead”.

Arriving at the nearest town, Zarathustra addresses a crowd which has gathered to watch a tightrope walker. He tells them that mankind’s goal must be to create something superior to itself – a new type of human, the Übermensch. All men, he says, must be prepared to will their own destruction in order to bring the Übermensch into being. The crowd greets this speech with scorn and mockery, and meanwhile the tightrope show begins.

When the rope-dancer is halfway across, a clown comes up behind him, urging him to get out of the way. The clown then leaps over the rope-dancer, causing the latter to fall to his death. The crowd scatters; Zarathustra takes the corpse of the rope-dancer on his shoulders, carries it into the forest, and lays it in a hollow tree. He decides that from this point on, he will no longer attempt to speak to the masses, but only to a few chosen disciples.

There follows a series of discourses in which Zarathustra overturns many of the precepts of Christian morality. He gathers a group of disciples, but ultimately abandons them, saying that he will not return until they have disowned him.

Second part

Zarathustra retires to his mountain cave, and several years pass by. One night, he dreams that he looks into a mirror and sees the face of a devil instead of his own; he takes this as a sign that his doctrines are being distorted