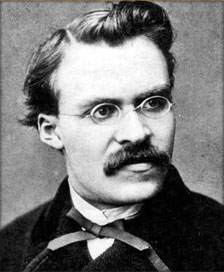

In verses 15 and 16, we have Nietzsche declaring himself an evolutionist in the broadest sense—that is to say, that he believes in the Development Hypothesis as the description of the process by which species have originated. Now, to understand his position correctly we must show his relationship to the two greatest of modern evolutionists—Darwin and Spencer. As a philosopher, however, Nietzsche does not stand or fall by his objections to the Darwinian or Spencerian cosmogony. He never laid claim to a very profound knowledge of biology, and his criticism is far more valuable as the attitude of a fresh mind than as that of a specialist towards the question. Moreover, in his objections many difficulties are raised which are not settled by an appeal to either of the men above mentioned. We have given Nietzsche’s definition of life in the Note on Chapter LVI., par. 10. Still, there remains a hope that Darwin and Nietzsche may some day become reconciled by a new description of the processes by which varieties occur. The appearance of varieties among animals and of “sporting plants” in the vegetable kingdom, is still shrouded in mystery, and the question whether this is not precisely the ground on which Darwin and Nietzsche will meet, is an interesting one. The former says in his “Origin of Species”, concerning the causes of variability: “…there are two factors, namely, the nature of the organism, and the nature of the conditions. THE FORMER SEEMS TO BE MUCH THE MORE IMPORTANT (The italics are mine.), for nearly similar variations sometimes arise under, as far as we can judge, dissimilar conditions; and on the other hand, dissimilar variations arise under conditions which appear to be nearly uniform.” Nietzsche, recognising this same truth, would ascribe practically all the importance to the “highest functionaries in the organism, in which the life-will appears as an active and formative principle,” and except in certain cases (where passive organisms alone are concerned) would not give such a prominent place to the influence of environment. Adaptation, according to him, is merely a secondary activity, a mere re-activity, and he is therefore quite opposed to Spencer’s definition: “Life is the continuous adjustment of internal relations to external relations.” Again in the motive force behind animal and plant life, Nietzsche disagrees with Darwin. He transforms the “Struggle for Existence”—the passive and involuntary condition—into the “Struggle for Power,” which is active and creative, and much more in harmony with Darwin’s own view, given above, concerning the importance of the organism itself. The change is one of such far-reaching importance that we cannot dispose of it in a breath, as a mere play upon words. “Much is reckoned higher than life itself by the living one.” Nietzsche says that to speak of the activity of life as a “struggle for existence,” is to state the case inadequately. He warns us not to confound Malthus with nature. There is something more than this struggle between the organic beings on this earth; want, which is supposed to bring this struggle about, is not so common as is supposed; some other force must be operative. The Will to Power is this force, “the instinct of self-preservation is only one of the indirect and most frequent results thereof.” A certain lack of acumen in psychological questions and the condition of affairs in England at the time Darwin wrote, may both, according to Nietzsche, have induced the renowned naturalist to describe the forces of nature as he did in his “Origin of Species”.

In verses 28, 29, and 30 of the second portion of this discourse we meet with a doctrine which, at first sight, seems to be merely “le manoir a l’envers,” indeed one English critic has actually said of Nietzsche, that “Thus Spake Zarathustra” is no more than a compendium of modern views and maxims turned upside down. Examining these heterodox pronouncements a little more closely, however, we may possibly perceive their truth. Regarding good and evil as purely relative values, it stands to reason that what may be bad or evil in a given man, relative to a certain environment, may actually be good if not highly virtuous in him relative to a certain other environment. If this hypothetical man represent the ascending line of life—that is to say, if he promise all that which is highest in a Graeco-Roman sense, then it is likely that he will be condemned as wicked if introduced into the society of men representing the opposite and descending line of life.

By depriving a man of his wickedness—more particularly nowadays— therefore, one may unwittingly be doing violence to the greatest in him. It may be an outrage against his wholeness, just as the lopping-off of a leg would be. Fortunately, the natural so-called “wickedness” of higher men has in a certain measure been able to resist this lopping process which successive slave-moralities have practised; but signs are not wanting which show that the noblest wickedness is fast vanishing from society—the wickedness of courage and determination—and that Nietzsche had good reasons for crying: “Ah, that (man’s) baddest is so very small! Ah, that his best is so very small. What is good? To be brave is good! It is the good war which halloweth every cause!” (see also par. 5, “Higher Man”).

Chapter LX. The Seven Seals.

This is a final paean which Zarathustra sings to Eternity and the marriage-ring of rings, the ring of the Eternal Recurrence.

…

Part IV.

In my opinion this part is Nietzsche’s open avowal that all his philosophy, together with all his hopes, enthusiastic outbursts, blasphemies, prolixities, and obscurities, were merely so many gifts laid at the feet of higher men. He had no desire to save the world. What he wished to determine was: Who is to be master of the world? This is a very different thing. He came to save higher men;—to give them that freedom by which, alone, they can develop and reach their zenith (see Note on Chapter LIV., end). It has been argued, and with considerable force, that no such philosophy is required by higher men, that, as a matter of fact, higher men, by virtue of their constitutions always, do stand Beyond Good and Evil, and never allow anything to stand in the way of their complete growth. Nietzsche, however, was evidently not so confident about this. He would probably have argued that we only see the successful cases. Being a great man himself, he was well aware of the dangers threatening greatness in our age. In “Beyond Good and Evil” he writes: “There are few pains so grievous as to have seen, divined, or experienced how an exceptional man has missed his way and deteriorated…” He knew “from his painfullest recollections on what wretched obstacles promising developments of the highest rank have hitherto usually gone to pieces, broken down, sunk, and become contemptible.” Now in Part IV. we shall find that his strongest temptation to descend to the feeling of “pity” for his contemporaries, is the “cry for help” which he hears from the lips of the higher men exposed to the dreadful danger of their modern environment.

Chapter LXI. The Honey Sacrifice.

In the fourteenth verse of this discourse Nietzsche defines the solemn duty he imposed upon himself: “Become what thou art.” Surely the criticism which has been directed against this maxim must all fall to the ground when it is remembered, once and for all, that Nietzsche’s teaching was never intended to be other than an esoteric one. “I am a law only for mine own,” he says emphatically, “I am not a law for all.” It is of the greatest importance to humanity that its highest individuals should be allowed to attain to their full development; for, only by means of its heroes can the human race be led forward step by step to higher and yet higher levels. “Become what thou art” applied to all, of course, becomes a vicious maxim; it is to be hoped, however, that we may learn in time that the same action performed by a given number of men, loses its identity precisely that same number of times.—“Quod licet Jovi, non licet bovi.”

At the last eight verses many readers may be tempted to laugh. In England we almost always laugh when a man takes himself seriously at anything save sport. And there is of course no reason why the reader should not be hilarious.—A certain greatness is requisite, both in order to be sublime and to have reverence for the sublime. Nietzsche earnestly believed that the Zarathustra-kingdom—his dynasty of a thousand years—would one day come; if he had not believed it so earnestly, if every artist in fact had not believed so earnestly in his Hazar, whether of ten, fifteen, a hundred, or a thousand years, we should have lost all our higher men; they would have become pessimists, suicides, or merchants. If the minor poet and philosopher has made us shy of the prophetic seriousness which characterized an Isaiah or a Jeremiah, it is surely our loss and the minor poet’s gain.

Chapter LXII. The Cry of Distress.

We now meet with Zarathustra in extraordinary circumstances. He is confronted with Schopenhauer and tempted by the old Soothsayer to commit the sin of pity. “I have come that I may seduce thee to thy last sin!” says the Soothsayer to Zarathustra. It will be remembered that in Schopenhauer’s ethics, pity is elevated to the highest