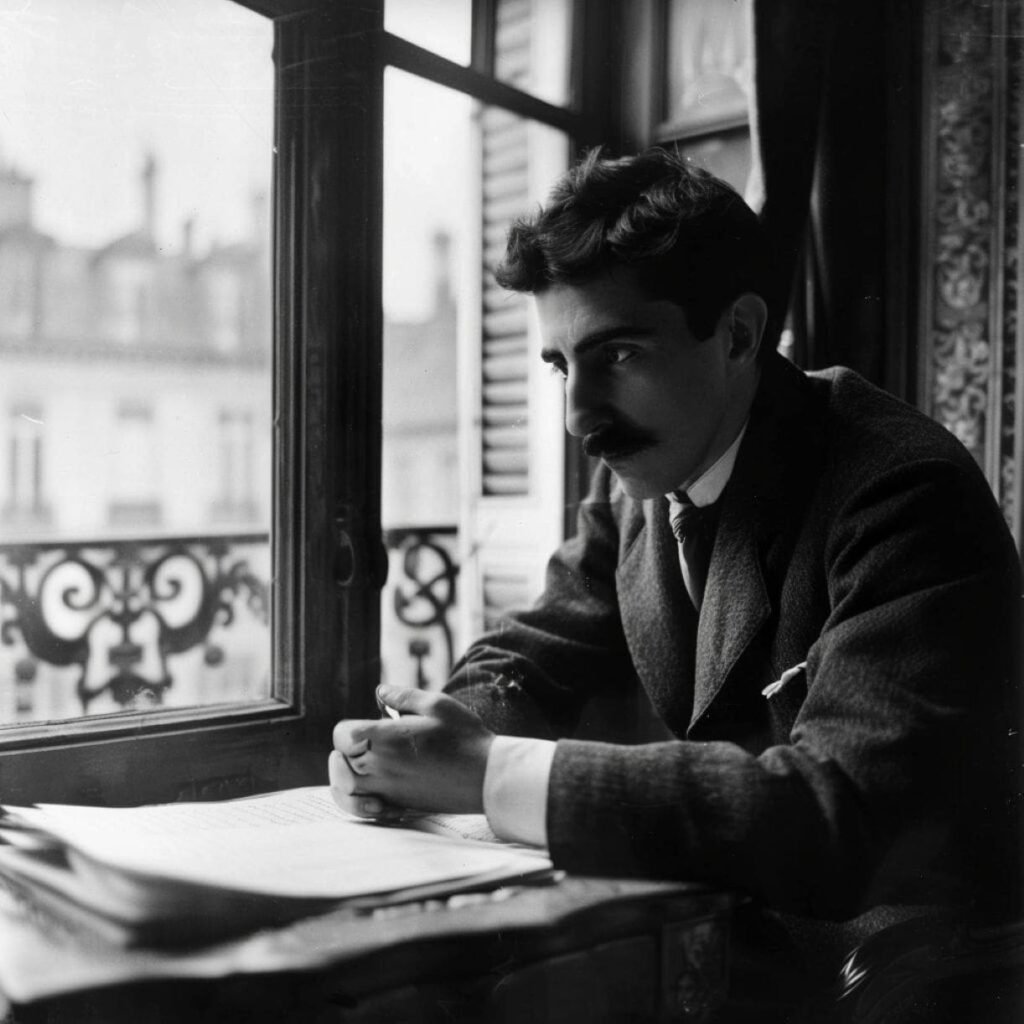

Fragments of Commedia dell’Arte, Marcel Proust

Fragments of Commedia dell’Arte

As crabs, goats, scorpions, the balance and the water-pot lose their meanness when hung as signs in the zodiac, so I can see my own vices without heat in . . . distant persons.

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON

Fabrizio’s Mistresses

Fabrizio’s mistress was intelligent and beautiful; he could not get over it. “She shouldn’t understand herself!” he groaned. “Her beauty is spoiled by her intelligence. Could I still be smitten with the Mona Lisa whenever I looked at her if I also had to hear a discourse by even a remarkable critic?”

He left her and took another mistress, who was beautiful and mindless. But her inexorable want of tact constantly prevented him from enjoying her charm. Moreover she aspired to intelligence, read a great deal, became a bluestocking, and was as intellectual as his first mistress, but with less ease and with ridiculous clumsiness.

He asked her to keep silent; but even when she held her tongue, her beauty cruelly reflected her stupidity. Finally he met a woman who revealed her intelligence purely in a more subtle grace, who was content with just living and never dissipated the enchanting mystery of her nature in overly specific conversations.

She was gentle, like graceful and agile animals with deep eyes, and she disturbed you like the morning’s vague and agonizing memory of your dreams. But she did not bother to do for him what his other two mistresses had done: she did not love him.

Countess Myrto’s Female Friends

Of all her friends, Myrto, witty, kind-hearted, and attractive, but with a taste for high society, prefers Parthénis, who is a duchess and more regal than Myrto; yet Myrto enjoys herself with Lalagé, who is exactly as fashionable as she herself; nor is Myrto indifferent to the charms of Cléanthis, who is obscure and does not aspire to a dazzling rank.

But the person Myrto cannot endure is Doris: her social position is slightly below Myrto’s, and she seeks Myrto out, as Myrto does Parthénis, for being more fashionable.

We point out these preferences and this antipathy because not only does Duchess Parthénis have an advantage over Myrto, but she can love Myrto purely for herself; Lalagé can love her for herself, and in any case, being colleagues and on the same level, they need each other; finally, in cherishing Cléanthis, Myrto proudly feels that she herself is capable of being unselfish, of having a sincere preference, of understanding and loving, and that she is fashionable enough to overlook fashionableness if necessary.

Doris, on the other hand, merely acts on her snobbish desires, which she is unable to fulfill; she visits Myrto like a pug approaching a mastiff that keeps track of its bones: Doris hopes thereby to have a go at Myrto’s duchesses and, if possible, shanghai one of them; disagreeable, like Myrto, because of the irksome disproportion between her actual rank and the one she strives for, she ultimately offers Myrto the image of her vice. To her chagrin, Myrto recognizes her friendship with Parthénis in Doris’s attentiveness to her, Myrto.

Lalagé and even Cléanthis remind Myrto of her ambitious dreams, and Parthénis at least has begun to make them come true: Doris talks to Myrto only about her paltriness. Thus, being too irritated to play the amusing role of patroness, Myrto feels in regard to Doris the emotions that she, Myrto, would inspire precisely in Parthénis if Parthénis were not above snobbery: Myrto hates Doris.

Heldémone, Adelgise, Ercole

After witnessing a slightly indelicate scene, Ercole is reluctant to describe it to Duchess Adelgise, but has no such qualms with Heldémone the courtesan.

“Ercole,” Adelgise exclaims, “you don’t think I can listen to that story? Ah, I’m quite sure you’d behave differently with the courtesan Heldémone. You respect me: you don’t love me.”

“Ercole,” Heldémone exclaims, “you don’t have the decency to conceal that story from me? You be the judge: would you act this way with Duchess Adelgise? You don’t respect me: therefore you cannot love me.”

The Fickle Man

Fabrizio, who wants to, who believes he will, love Béatrice forever, remembers that he wanted the same thing, believed the same thing when he loved Hippolyta, Barbara, and Clélie for six months.

So, reviewing Béatrice’s actual qualities, he tries to find a reason to believe that after the waning of his passion he will keep visiting her; for he finds the thought of someday living without her incompatible with a sentiment that contains the illusion of its own eternalness. Besides, as a prudent egoist, he would not care to commit himself fully—with his thoughts, his actions, his intentions of the moment and all his future plans—to the companion of only some of his hours.

Béatrice has a sharp mind and a good judgment: “Once I stop loving her, what pleasure I’ll feel chatting with her about others, about herself, about my vanished love for her . . .” (which will thereby be revived but converted, he hopes, into a more lasting friendship).

But, with his passion for Béatrice gone, he lets two years pass without visiting her, without wanting to see her, without suffering from not wanting to see her. One day, when forced to visit her, he sits there fuming and stays for only ten minutes. For he dreams night and day about Giulia, who is unusually mindless but whose fair hair smells as good as a fine herb and whose eyes are as innocent as two flowers.

Life is strangely easy and pleasant with certain people of great natural distinction, people who are witty, loving, but who are capable of all vices although they do not indulge in any vice publicly, so no one can state that they have any vice at all. There is something supple and secretive about them. Then too, their perversity adds a piquant touch to their most innocent actions such as strolling in gardens at night.

Lost Waxes

ONE

I first saw you a little while ago, Cydalise, and right off I admired your blond hair, like a small gold helmet on your pure and melancholy childlike head. A slightly pale red velvet gown softened your unusual head even further, and the lowered eyelids appeared to seal its mystery forever. But then you raised your eyes; they halted on me, Cydalise, and they seemed imbued with the fresh purity of morning, of water running on the first lovely days in spring. Those eyes were like eyes that have never looked at the things that all human eyes are accustomed to reflecting—yours were virginal eyes without earthly experience.

But upon my closer scrutiny, you expressed, above all, an air of loving and suffering, like a person whose wishes were already denied by the fairies before his birth. Even fabrics assumed a sorrowful grace on you, casting a gloom especially on your arms, which were discouraged just enough to remain simple and charming.

Then I pictured you as a princess coming from very far away, down through the centuries, bored forever here and with a resigned languor: a princess wearing garments of a rare and ancient harmony, the contemplation of which would have quickly turned into a sweet and intoxicating habit for the eyes.

I would have wanted you to tell me your dreams, your cares. I would have wanted to see you hold some goblet or rather one of those ewers with such proud and joyless forms, ewers that, empty in our museums today, raise their drained cups with a useless grace; and yet once, like you, they constituted the fresh sensual pleasures of Venetian banquets, whose final violets and final roses seem to be still floating in the limpid current of the foamy and cloudy glass.

TWO

“How can you prefer Hippolyta to the five others I’ve just named: why, they’re the most undeniably beautiful women in Verona. First of all, her nose is too long and too aquiline.”

You can add that her complexion is too fine, that her upper lip is too narrow, and that, by pulling her mouth up too high when she laughs, it creates a very acute angle.

Yet I am infinitely affected by her laughter, and the purest profiles leave me cold next to the line of her nose, which you feel is too aquiline, but which I find so exciting and so reminiscent of a bird. Her head, long as it is from her brow to her blond nape, is also slightly birdlike, as are, even more so, her gentle, piercing eyes.

At the theater she often rests her elbows on the railing of her box: her hand, in a white glove, shoots straight up to her chin, which leans on her finger joints. Her perfect body makes her customary white gauzes swell like folded wings. She reminds you of a bird dreaming on a slender and elegant leg. It is also delightful to see her feathery fan throbbing next to her and beating its white wing.

Her sons and her nephews all have, like her, aquiline noses, narrow lips, piercing eyes, and overly fine complexions, and I have never managed to meet them without being distressed when recognizing her breed, which probably descends from a goddess and a bird. Through the metamorphosis that now fetters some winged desire to this female shape, I can discern the small royal head of the peacock without the froth or the ocean-blue, ocean-green wave of the peacock’s mythological plumage glittering behind the head. She is the epitome of fable blended with the thrill of beauty.

Snobs

ONE

A woman does not mask her love of balls, horse races, even gambling. She states it or simply admits it or boasts about it. But never try to make her say that she