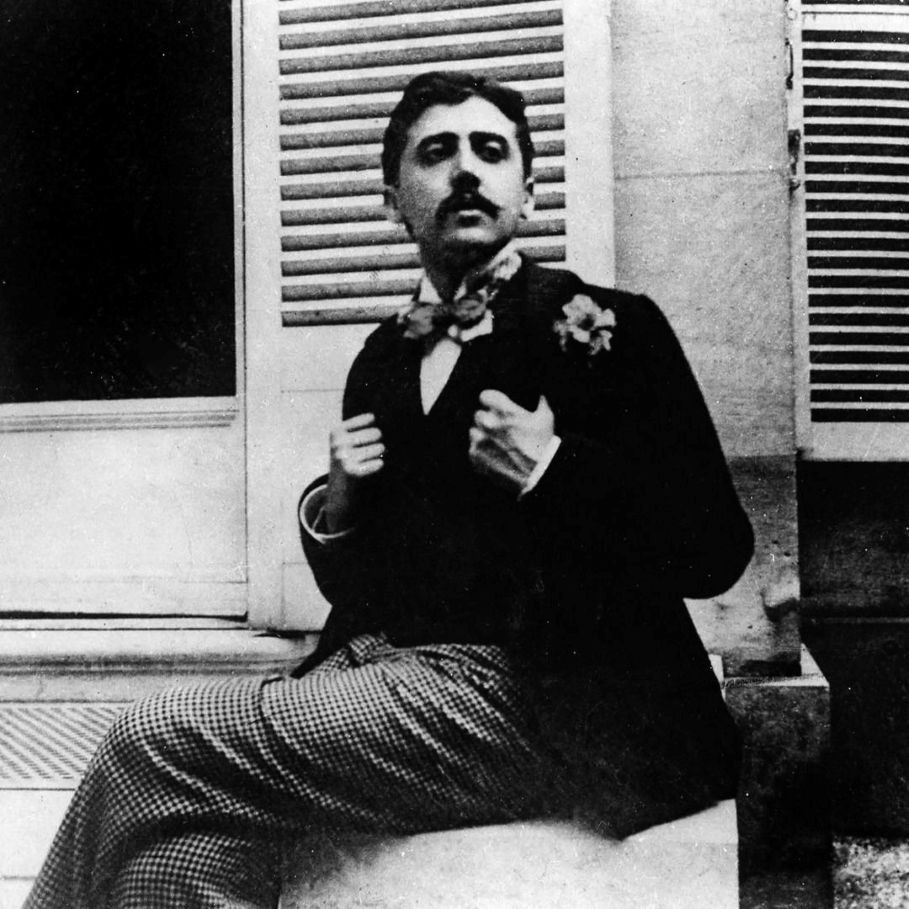

Norman Things, Marcel Proust

Norman Things

Trouville, the capital of the canton, with a population of 6,808, can lodge 15,000 guests in the summer.

—GUIDE JOANNE

For Paul Grünebaum

For several days now we have been able to contemplate the calm of the sea in the sky, which has become pure again—contemplate it as one contemplates a soul in a gaze. No one, however, is left to enjoy the follies and serenities of the September sea, for it is fashionable to desert the beaches at the end of August and head for the country.

But I envy and, if acquainted with them, I often visit people whose countryside lies by the sea, is located, for example, above Trouville. I envy the person who can spend the autumn in Normandy, however little he knows how to think and feel.

The terrain, never very cold even in winter, is the greenest there is, grassy by nature, without the slightest gap, and even on the other sides of the hillocks, in the amiable arrangements called “woodlands.”

Often, when on a terrace, where the blond tea is steaming on the set table, you can, as Baudelaire puts it, watch “the sunshine radiating on the sea” and sails that come, “all those movements of people departing, people who still have the strength to desire and to wish.”

In the so sweet and peaceful midst of all that greenery, you can look at the peace of the seas, or the tempestuous sea, and the waves crowned with foam and gulls, charging like lions, their white manes rippling in the wind.

However, the moon, invisible to all the waves by day, though still troubling them with its magnetic gaze, tames them, suddenly crushes their assault, and excites them again before repelling them, no doubt to charm the melancholy leisures of the gathering of stars, the mysterious princes of the maritime skies.

A person who lives in Normandy sees all that; and if he goes down to the shore in the daytime, he can hear the sea sobbing to the beat of the surges of the human soul, the sea, which corresponds to music in the created world, because, showing us no material thing and not being descriptive in its way, the sea sounds like the monotonous chant of an ambitious and faltering will.

In the evening, the Normandy dweller goes back to the countryside, and in his gardens he cannot distinguish between sky and sea, which blend together. Yet they appear to be separated by that brilliant line; above it that must be the sky.

That must be the sky, that airy sash of pale azure, and the sea drenches only the golden fringes. But now a vessel puts a graft upon it while seeming to navigate in the midst of the sky. In the evening, the moon, if shining, whitens the very dense vapors rising from the grasslands, and, gracefully bewitched, the field looks like a lake or a snow-covered meadow.

Thus, this rustic area, which is the richest in France, which, with its inexhaustible abundance of farms, cows, cream, apple trees for cider, thick grass, invites you solely to eat and sleep—at night this countryside decks itself out with mystery, and its melancholy rivals that of the vast plain of the sea.

Finally, there are several utterly desirable abodes, a few assailed by the sea and protected against it, others perched on the cliff, in the middle of the woods, or amply stretched out on grassy plateaus.

I am not talking about the “Oriental” or “Persian” houses, which would be more agreeable in Teheran; I mean, above all, the Norman homes—in reality half-Norman, half-English—in which the profusion of the finials of roof timbers multiplies the points of view and complicates a silhouette, in which the windows, though broad, are so tender and intimate, in which, from the flower boxes in the wall under each window, the flowers cascade inexhaustibly upon the outside stairs and the glassed-in entrance halls.

It is to one of those houses that I go home, for night is falling, and I will reread, for the hundredth time, Confiteor by the poet Gabriel Trarieux. . . .

The end