On Reading, Proust, Marcel

On Reading

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

On Reading Translator’s Preface to Sesame and Lilies

Lecture I — Sesame. Of Kings’ Treasuries by John Ruskin, Notes by Marcel Proust

Makeshift Memory

Ruskin in Venice

Servitude and Freedom

Resurrection

Foreword

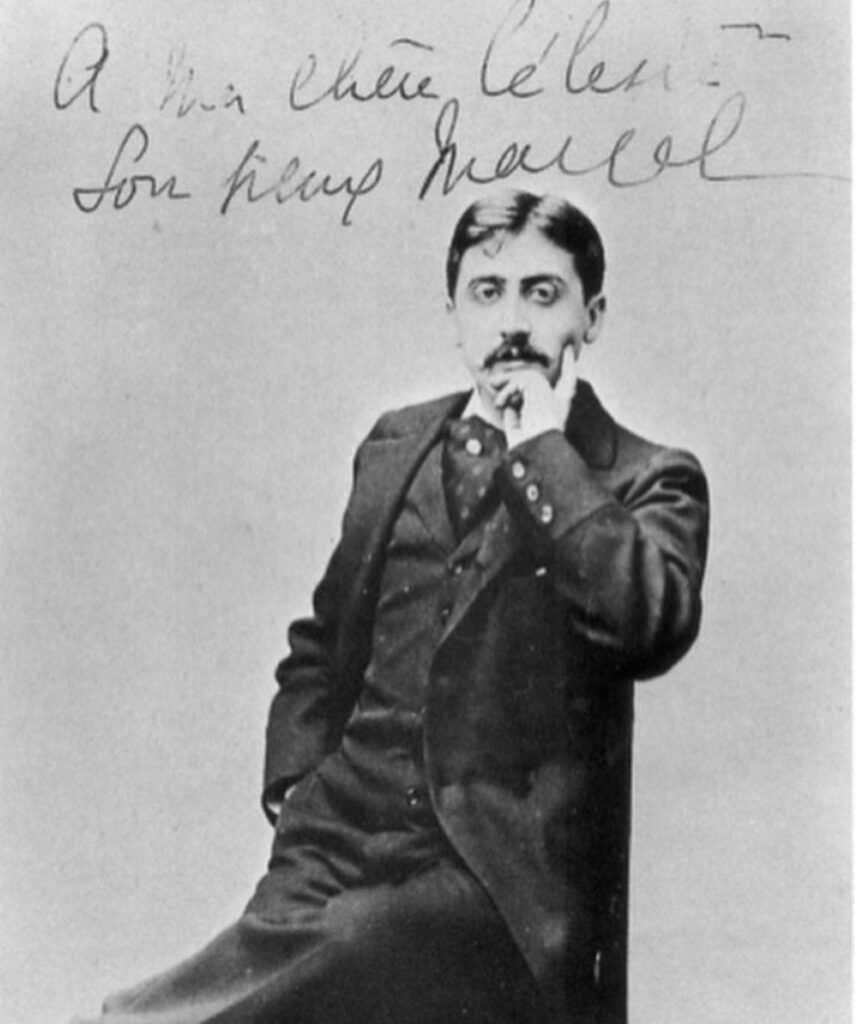

Between the writing of Jean Santeuil and A la recherche du temps perdu, Marcel Proust committed many years to his translations of Ruskin and their accompanying notes and forewords. Ruskin’s voice was engaging, personal and accessible: ‘May I ask you to consider with me what this idea practically includes?’ the eminent Victorian inquired politely about the concept of one’s having a ‘position in life’. Proust, whose gift as a translator came not from language skills but rather from a profound comprehension of his subject, struggled to make Ruskin’s English come alive in French.

What we have in Damion Searls’s present selection of Proust’s prefaces to Ruskin is an almost Wildean farce of accumulated attributions: I am writing a foreword to his translation of Proust’s introductions to his own translations of Ruskin. (‘I’m sure the programme will be delightful, after a few expurgations’, as Lady Bracknell says.)

In a volume called Sesame and Lilies, evoking the masculine and feminine, the foremost English cultural critic of his time collected a series of lectures he had given on the opposing natures of man and woman. In these talks, Ruskin expounded upon the virtue of books and the importance of reading as an edifying activity. ‘If you do not know the Greek alphabet, learn it’, John Ruskin pleaded to his audience, associating classical values and art’s moral imperatives. To discriminate between lighter fare – newspapers, fiction, travel diaries – and more substantive literary endeavors, he made the claim that ‘a book is essentially not a talking thing, but a written thing’.

As I made my way through this selection, I was struck otherwise. ‘Of Kings’ Treasuries’ from Sesame and Lilies seemed to me to be very much ‘a talking thing’ indeed; how intensely aural the experience of reading it proved to be. The resounding voices of Proust and Ruskin can be heard as well as read in these pages.

And by juxtaposing the English philosopher with his French disciple, Searls affords us the rare privilege of overhearing Proust’s mind engage with Ruskin in what is tantamount to spoken dialogue. From across the divide of 100 years, we hear Proust vocalise clearly and directly: ‘Need I add that if I describe this taste, this kind of fetishistic reverence for books as unhealthy and pernicious, it is only relative to the ideal habits of a spirit altogether lacking in faults, one which does not exist; I do so like the physiologists who describe as an organ’s normal function something which is hardly ever found in living beings.’ In these pages the writer is not hiding behind a scrim of narrative fiction, so our connection to his verbose, complex sensibility feels more immediate, more revealing. Here we find fully realised the voice first developed in Les plaisirs et les jours, later to be fructified in Contre Sainte-Beuve.

According to Ruskin a book may not be essentially a ‘talking thing’, yet he put forth the proposition that ‘reading is a conversation’. Proust, however, maintained that ‘reading cannot be equated to conversation’, insisting that one reads only in a condition of solitude. Meanwhile, reading these comments, I felt he was speaking within earshot, as if I overheard him speaking at a café table next to mine.

Despite his insistence upon the necessity of solitude, Proust developed an engaging writing style that is decidedly conversational, nearly chatty. And his voice is not the only one we hear.

Proust calls forth other voices in these pages, cuing entries at precise moments from Matthew Arnold, Anatole France, Emerson, Racine, John Stuart Mill, George Eliot, Shakespeare. Passages from the highly colloquial King James Bible are inserted. Proust is like a literary choirmaster, and resembles the humble pianist who sits down to play for Mme Verdurin, causing her to exclaim, ‘je crois entendre un orchestre’.

Much as Proust absorbed Pelléas while tuning in his Théâtrophone broadcast, we too, reading these texts, can make out distinct, rapturous voices. In a felicitous harmony of eye and ear, I felt I was actually listening to what I was reading.

Proust devoted eight years of apprenticeship to the quirky English critic. His intoxication with Ruskin’s aesthetic is palpable and the reader feels a renewed sense of the deep debt gratefully incurred. ‘There is no better way to discover what you yourself feel than to try and recreate in yourself what a master has felt.’ At the same time, reading these pages, one bears witness to the end of the affair. Proust had come under the sway of Whistler, apostle of ‘art for art’s sake’, whose legal battle with Ruskin had forced him to flee London for Paris. (Proust and Ruskin never met. Proust and Whistler met once, in 1897.)

The conflicting insights Proust extracted from these two larger-than-life characters needed constructive reconciliation so as to avoid negation, and in a note found in these pages, he articulated a solution to a seemingly intractable standoff of belief systems: ‘…these opposites may perhaps meet if one extends the two ideas, not all the way to infinity, but to a certain height’. This was just what Proust was to do, eventually coming to understand that between Ruskin and Whistler ‘there was only one truth and they both perceived it.’

Having brought to completion the consuming labor of his translations, Proust then began to address the integrity of Ruskin’s ultimate accomplishment.

He found serious fault and undertook an impassioned dissection of his master’s philosophical weaknesses. Then, with the righteousness of a lapsed believer, he generously ascribed Ruskin’s failings to ‘an essential frailty of the human spirit’. Proust’s biographer Tadié succinctly sums up this process of chrysalis as ‘a dialectic of influence, which extends from identification to refutation, and from refutation to assimilation’.

Finally, after the give and take of serious analytic criticism, after the protracted immersion in another writer’s words, the sleeping novelist was roused. Efficiently, Proust converted much of what he learned from Ruskin into practical, technical information. Reading the notes in these pages, we feel the emergence of the incomparable practitioner-to-be.

Proust bristled at Ruskin’s disdain for ‘wise men’ who ‘hide their deeper thought’, and offered instead his own observations, created his own hierarchy of thinkers. ‘The writer of the first rank is one who uses whatever words are dictated to him by an interior necessity, the vision of his thought which he cannot alter in the least.’

Flaubert is held high, Sentimental Education extolled. We read of those first-rate books and the writers who ‘build and perfect the necessary and unique form’ where their thoughts ‘will be made incarnate’. Proust’s notes and prefaces to Ruskin reveal the exacting mind of a literary critic operating from the vantage point of a structural engineer. Responding to ‘Of Kings’ Treasuries’, Proust constructed around Ruskin’s text a verbal retaining wall sturdy enough to withstand the assault of his own commentary.

Extrapolating architectural details cited in The Bible of Amiens, he reconsidered the integral configuration of the novel. In ‘On Reading’, Proust’s preface to Sesame and Lilies, we come closest to a recipe for the mortar and bricks that laid the foundation for A la Recherche du temps perdu:

He moves from one idea to the next without any apparent order, but in reality the imagination which conducts them is following its own deep affinities and imposing on it, despite itself, a higher logic, to such an extent that at the end it finds itself to have obeyed a kind of secret plan which, unveiled at the end, retroactively imposes a kind of order on the whole and makes it seem magnificently staged right up to the climax of this final apotheosis.

These reflections on Ruskin’s compositional methodology provide us with a foretaste of Proust’s understanding of his own forthcoming apotheosis. He would shortly abandon the need to recreate in himself what a master had felt. Instead, he became one.

– Eric Karpeles, 2011

Introduction

I realised that the essential book, the one true book, is one that the great writer does not need to invent, in the current sense of the word, since it already exists in every one of us – he has only to translate it. The task and the duty of a writer are those of a translator.

– Remembrance of Things Past: Time Regained

Although many great writers have also been translators – Borges, Murakami, Singer, Rilke, just to start at the top – there is perhaps no writer of such stature for whom translation was as important as it was for Marcel Proust. He spent eight years immersed in John Ruskin’s work and six years translating two of his books, a discipline which profoundly shaped his art and style. Ruskin in fact became for Proust in his late twenties almost exactly what Rodin would be for Rilke in his late twenties: an older mentor whose creativity through submission, through concrete attention to physical form (Gothic cathedrals, sculpture), would give the dreamy, frustrated younger artist the discipline and confidence he needed to construct forms in words for own his inner world. Even the mottos they drew from their respective mentors were almost identical: from Ruskin, ‘Work while you still have light’; from Rodin, ‘Travailler, rien de travailler.’

In 1897, Proust (1871-1923) had written close to a thousand pages of a long novel, Jean Santeuil, but found himself unable to pull the book together.1 At this time of crisis, he read Robert de La Sizeranne’s article (later a long book) ‘Ruskin et la religion de beautê. Although little read today, John Ruskin (1819-1900) was one