Proust’s Dedication, Marcel Proust

Proust’s Dedication

To My Friend Willy Heath Died in Paris on October 3, 1893

From the bosom of God wherein you rest . . . reveal to me those truths that conquer death, preventing us from fearing it and almost making us love it.

The ancient Greeks brought cakes, milk, and wine to their dead. Seduced by a more refined if not more sagacious illusion, we offer them flowers and books.

I give you this book because, for one thing, it is a picture book. Despite the “legends,” it will be, if not read, then at least viewed by all the admirers of the great artist who has, in all her simplicity, brought me this magnificent present.

One could say that, to quote Alexandre Dumas, the younger, “it is she who has created the most roses after God.” Monsieur Robert de Montesquiou, in still unpublished verses, has also sung her praises with that ingenious gravity, that sententious and subtle eloquence, that rigorous order that sometimes recalls the seventeenth century. In speaking about flowers he told her:

To pose for your brushes impels them to blossom.

You are their Vigée and you are their Flora,

Who makes them immortal while the other one kills.

Her admirers are an elite, yet they form a throng. I wanted them to see your name on the very first page, the name of the person whom they had no time to get to know and whom they would have admired.

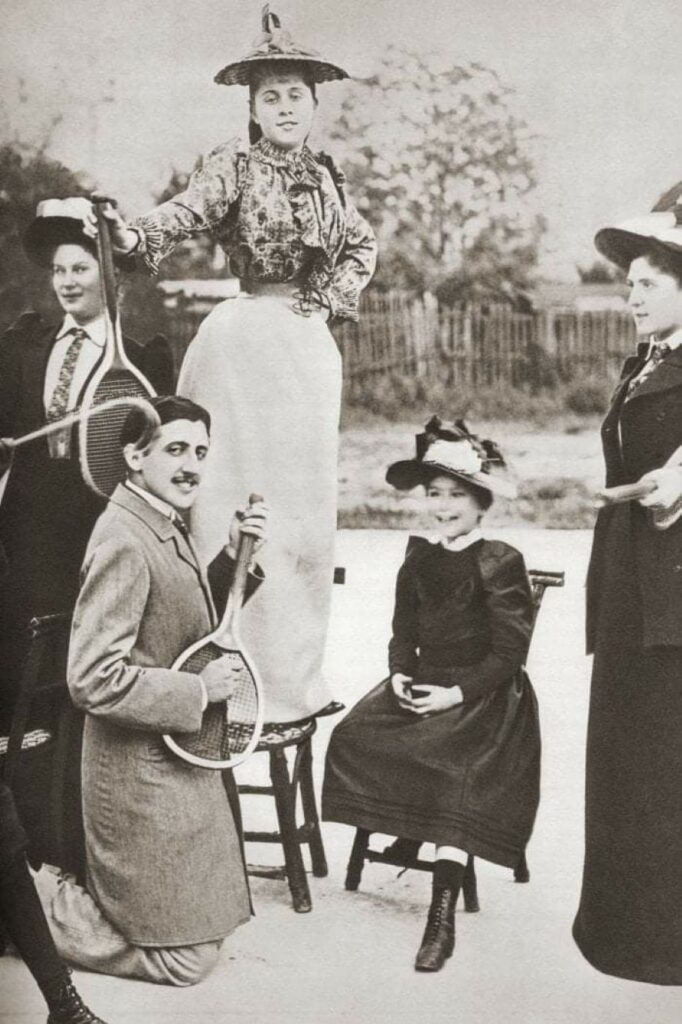

I myself, dear friend, I knew you very briefly. It was in the Bois de Boulogne that I found you on numerous mornings when you had noticed me and awaited me under the trees, standing, but relaxed, like one of Van Dyck’s aristocrats, whose pensive elegance you shared. Indeed, their elegance, like yours, resides less in their clothes than in their bodies, and their bodies themselves appear to have received it and to keep receiving it from their souls: it is a moral elegance.

Everything, incidentally, contributed to emphasizing that melancholy resemblance down to the leafy background in whose shade Van Dyck often captured the strolling of a king. Like so many of his sitters, you had to die an early death, and in your eyes as in theirs, one could see the gloom of forebodings alternating with the soft light of resignation. But if Van Dyck’s art could properly be credited with the grace of your pride, the mysterious intensity of your spiritual life actually derived from Da Vinci.

Frequently, with your finger raised, your impenetrable eyes smiling at the enigma that you concealed, you looked like Leonardo’s Saint John the Baptist. We developed a dream, almost a plan, to live together more and more, in a circle of select and magnanimous women and men, far enough from vice, stupidity, and malice to feel safe from their vulgar shafts.

Your life, such as you wished it, was to be one of those works that require a sublime inspiration. We could derive inspiration from love as we could from faith and genius. But it was death that would give it to you.

In death and even in its approach there are hidden forces and secret aids, a “grace” that does not exist in life. Akin to lovers when falling in love, akin to poets when singing, ill people feel closer to their souls.

Life is a hard thing that presses us too tightly, forever hurting our souls. Upon feeling those restraints loosen for a moment, one can experience clear-sighted pleasures.

When I was a little boy, no biblical figure struck me as suffering a more wretched fate than Noah, because of the Deluge that imprisoned him in the ark for forty days. Later on I was often sick and I, too, had to spend long days in the “ark.”

I now understood that Noah could not have seen the world so clearly as from the ark, even though the ark was shut and the earth was shrouded in night.

When my convalescence began, my mother, who had not left my side, remaining with me every night, “opened the door of the ark” and left. Yet like the dove, “she returned that evening.” Then I was fully recovered, and like the dove, “she did not return.”

I had to resume living, to turn away from myself, to hear words harsher than my mother’s; furthermore, her words, always gentle until this point, were no longer the same; they were stamped with the severity of life, the severity of the duties that she had to teach me.

Gentle dove of the Deluge, how could I but think that the Patriarch, in seeing you flutter away, felt some sadness mingling with the joy at the rebirth of the world.

Gentleness of the abeyance of life, gentleness of the real “Truce of God,” which suspends labors, evil desires, “Grace” of the illness that brings us closer to the realities beyond death—and its charms, too, charms of “those vain ornaments and those veils that crush,” charms of the hair that an obtrusive hand “took care to arrange”; a mother’s and a friend’s sweet signs of fidelity, which have so often looked like the very face of our sadness or like the protective gesture begged for by our weakness, signs that will halt at the threshold of convalescence—I have often suffered at feeling you so far away from me, all of you, the exiled descendants of the dove in the ark.

And who among us has not had moments, dear Willy, when he has wanted to be where you are. We accept so many commitments in regard to life that a time comes when, despairing of ever managing to fulfill them all, we face the graves, we call upon death, “death, which brings help to destinies that have trouble coming true.”

But while death may exempt us from commitments we have made in regard to life, it cannot exempt us from our commitments to ourselves, especially the most important one: namely, the commitment to live in order to be worthy and deserving.

More earnest than the rest of us, you were also the most childlike, not only because of your purity of heart, but also because of your unaffected and delightful merriment. Charles de Grancy had a gift for which I envy him: by recalling school days he could abruptly arouse that laughter, which was never dormant for long and which we will never hear again.

While a few of these pages were written when I was twenty-three, many others (“Violante,” nearly all the “Fragments of Commedia dell’Arte,” etc.) go back to my twentieth year. They are all nothing but the vain foam of an agitated life that is now calming down. May my life someday be so limpid that the Muses will deign to mirror themselves in it and that we can see the reflections of their smiles and their dances skimming across its surface.

I give you this book. You are, alas, my only friend whose criticism it need not fear. I am at least confident that no freedom of tone would have shocked you anywhere. I have never depicted immorality except in people with delicate consciences. Too feeble to want good, too noble to fully enjoy evil, they know nothing but suffering; I therefore could speak about them only with a pity too sincere not to purify these little texts.

I hope that the true friend and the illustrious and beloved Master—who gave them, respectively, the poetry of his music and the music of his incomparable poetry—and also Monsieur Darlu, the great philosopher, whose inspired words, more certain to endure than any writings, have stirred my mind and so many other minds—I hope they can forgive me for reserving for you this final token of affection and I hope they realize that a living man, no matter how great or dear, can be honored only after a dead man.

July 1894

The end