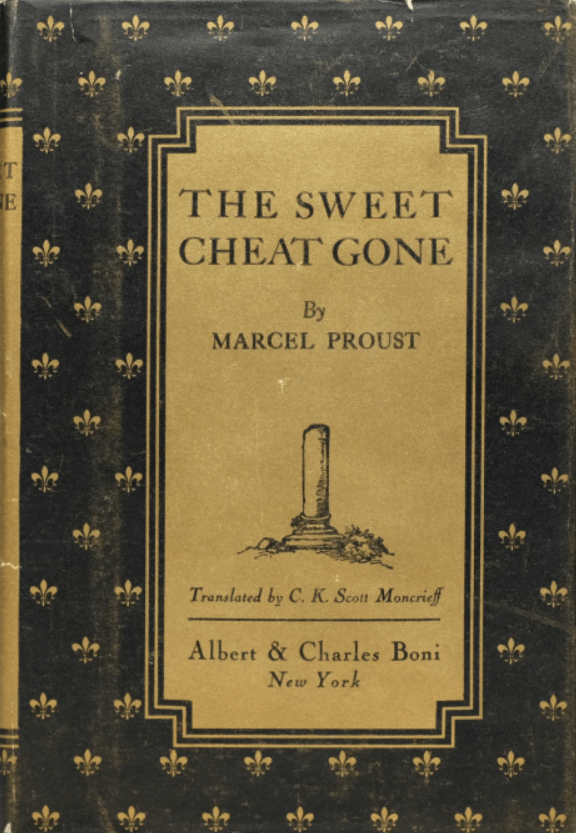

In Search of Lost Time Vol 6, The Sweet Cheat Gone (Albertine disparue) Marcel Proust

The Sweet Cheat Gone (Albertine disparue)

Zugeeignet

Obwohl die arme Albertine verschwunden ist,

haben die Brüder Albrecht gut gewusst

wie uns zu trösten.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE Grief and oblivion

CHAPTER TWO Mademoiselle de Forcheville

CHAPTER THREE Venice

CHAPTER FOUR A fresh light upon Robert de Saint-Loup

THE SWEET CHEAT GONE

CHAPTER ONE

GRIEF AND OBLIVION

“Mademoiselle Albertine has gone!” How much farther does anguish penetrate in psychology than psychology itself! A moment ago, as I lay analysing my feelings, I had supposed that this separation without a final meeting was precisely what I wished, and, as I compared the mediocrity of the pleasures that Albertine afforded me with the richness of the desires which she prevented me from realising, had felt that I was being subtle, had concluded that I did not wish to see her again, that I no longer loved her. But now these words:

“Mademoiselle Albertine has gone!” had expressed themselves in my heart in the form of an anguish so keen that I would not be able to endure it for any length of time. And so what I had supposed to mean nothing to me was the only thing in my whole life.

How ignorant we are of ourselves. The first thing to be done was to make my anguish cease at once. Tender towards myself as my mother had been towards my dying grandmother, I said to myself with that anxiety which we feel to prevent a person whom we love from suffering: “Be patient for just a moment, we shall find something to take the pain away, don’t fret, we are not going to allow you to suffer like this.” It was among ideas of this sort that my instinct of self-preservation sought for the first sedatives to lay upon my open wound: “All this is not of the slightest importance, for I am going to make her return here at once. I must think first how I am to do it, but in any case she will be here this evening.

Therefore, it is useless to worry myself.” “All this is not of the slightest importance,” I had not been content with giving myself this assurance, I had tried to convey the same impression to Françoise by not allowing her to see what I was suffering, because, even at the moment when I was feeling so keen an anguish, my love did not forget how important it was that it should appear a happy love, a mutual love, especially in the eyes of Françoise, who, as she disliked Albertine, had always doubted her sincerity.

Yes, a moment ago, before Françoise came into the room, I had supposed that I was no longer in love with Albertine, I had supposed that I was leaving nothing out of account; a careful analyst, I had supposed that I knew the state of my own heart. But our intelligence, however great it may be, cannot perceive the elements that compose it and remain unsuspected so long as, from the volatile state in which they generally exist, a phenomenon capable of isolating them has not subjected them to the first stages of solidification. I had been mistaken in thinking that I could see clearly into my own heart. But this knowledge which had not been given me by the finest mental perceptions had now been brought to me, hard, glittering, strange, like a crystallised salt, by the abrupt reaction of grief. I was so much in the habit of seeing Albertine in the room, and I saw, all of a sudden, a fresh aspect of Habit. Hitherto I had regarded it chiefly as an annihilating force which suppresses the originality and even our consciousness of our perceptions; now I beheld it as a dread deity, so riveted to ourselves, its meaningless aspect so incrusted in our heart, that if it detaches itself, if it turns away from us, this deity which we can barely distinguish inflicts upon us sufferings more terrible than any other and is then as cruel as death itself.

The first thing to be done was to read Albertine’s letter, since I was anxious to think of some way of making her return. I felt that this lay in my power, because, as the future is what exists only in our mind, it seems to us to be still alterable by the intervention, in extremis, of our will. But, at the same time, I remembered that I had seen act upon it forces other than my own, against which, however long an interval had been allowed me, I could never have prevailed. Of what use is it that the hour has not yet struck if we can do nothing to influence what is bound to happen. When Albertine was living in the house I had been quite determined to retain the initiative in our parting. And now she had gone. I opened her letter. It ran as follows:

“MY DEAR FRIEND,

“Forgive me for not having dared to say to you in so many words what I am now writing, but I am such a coward, I have always been so afraid in your presence that I have never been able to force myself to speak. This is what I should have said to you. Our life together has become impossible; you must, for that matter, have seen, when you turned upon me the other evening, that there had been a change in our relations. What we were able to straighten out that night would become irreparable in a few days’ time. It is better for us, therefore, since we have had the good fortune to be reconciled, to part as friends. That is why, my darling, I am sending you this line, and beg you to be so kind as to forgive me if I am causing you a little grief when you think of the immensity of mine. My dear old boy, I do not wish to become your enemy, it will be bad enough to become by degrees, and very soon, a stranger to you; and so, as I have absolutely made up my mind, before sending you this letter by Françoise, I shall have asked her to let me have my boxes. Good-bye: I leave with you the best part of myself.

“ALBERTINE.”

“All this means nothing,” I told myself, “It is even better than I thought, for as she doesn’t mean a word of what she says she has obviously written her letter only to give me a severe shock, so that I shall take fright, and not be horrid to her again. I must make some arrangement at once: Albertine must be brought back this evening. It is sad to think that the Bontemps are no better than blackmailers who make use of their niece to extort money from me. But what does that matter? Even if, to bring Albertine back here this evening, I have to give half my fortune to Mme. Bontemps, we shall still have enough left, Albertine and I, to live in comfort.” And, at the same time, I calculated whether I had time to go out that morning and order the yacht and the Rolls-Royce which she coveted, quite forgetting, now that all my hesitation had vanished, that I had decided that it would be unwise to give her them. “Even if Mme. Bontemps’ support is not sufficient, if Albertine refuses to obey her aunt and makes it a condition of her returning to me that she shall enjoy complete independence, well, however much it may distress me, I shall leave her to herself; she shall go out by herself, whenever she chooses.

One must be prepared to make sacrifices, however painful they may be, for the thing to which one attaches most importance, which is, in spite of everything that I decided this morning, on the strength of my scrupulous and absurd arguments, that Albertine shall continue to live here.” Can I say for that matter that to leave her free to go where she chose would have been altogether painful to me? I should be lying. Often already I had felt that the anguish of leaving her free to behave improperly out of my sight was perhaps even less than that sort of misery which I used to feel when I guessed that she was bored in my company, under my roof. No doubt at the actual moment of her asking me to let her go somewhere, the act of allowing her to go, with the idea of an organised orgy, would have been an appalling torment. But to say to her: “Take our yacht, or the train, go away for a month, to some place which I have never seen, where I shall know nothing of what you are doing,”—this had often appealed to me, owing to the thought that, by force of contrast, when she was away from me, she would prefer my society, and would be glad to return. “This return is certainly what she herself desires; she does not in the least insist upon that freedom upon which, moreover, by offering her every day some fresh pleasure, I should easily succeed in imposing, day by day, a further restriction. No, what Albertine has wanted is that I shall no longer make myself unpleasant to her, and most of all—like Odette with Swann—that I shall make up my mind to marry her. Once she is married, her independence will cease to matter; we shall stay here together, in perfect happiness.” No doubt this meant giving up any thought of