A Morning of a Landed Proprietor Or A Russian Proprietor, A Landowner’s Morning, Leo Tolstoy

A Morning of a Landed Proprietor Or A Russian Proprietor

An Unfinished Novel

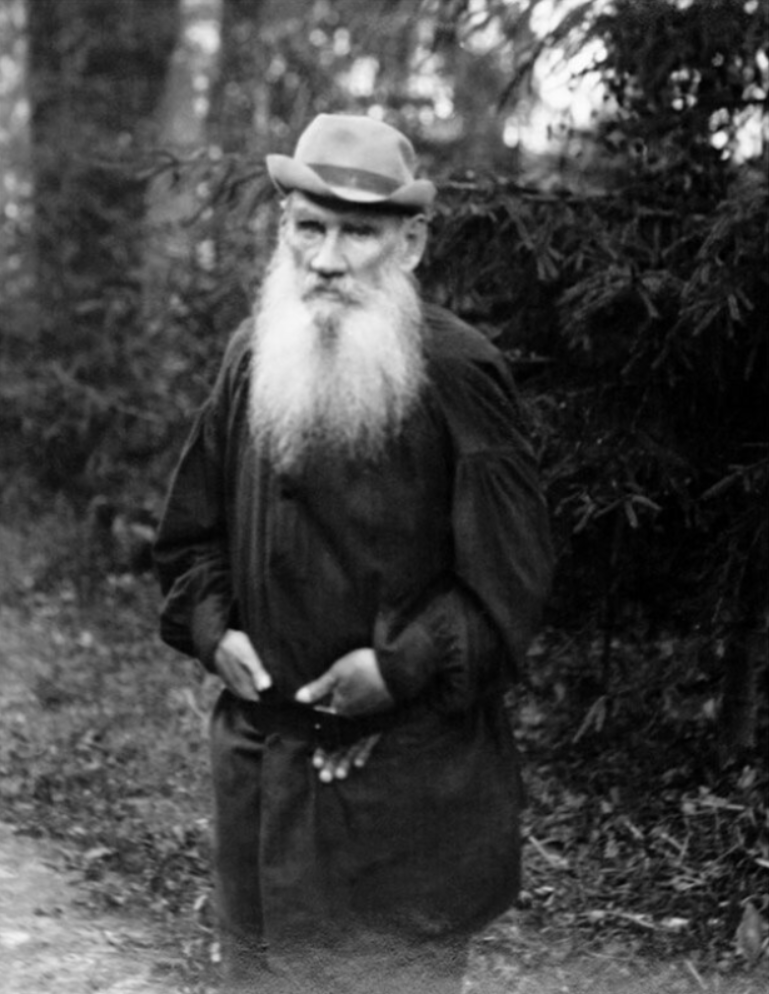

Tolstoy lived on his family estate until 1851, when his brother, an artillery officer, convinced him to visit Caucasia. Charmed by the life there, he joined an artillery regiment and in 1853 was attached to the army of the Danube during the Crimean campaign. During this time he wrote The Morning of a Landed Proprietor, which he intended to be a novel. However, the work was left unfinished and was only rediscovered after Tolstoy’s death.

A Morning of a Landed Proprietor

Contents

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

I

PRINCE NEKHLYUDOV WAS nineteen years old when he came from the Third Course of the university to pass his vacation on his estate, and remained there by himself all summer. In the autumn he wrote in his unformed childish hand to his aunt, Countess Byeloryetski, who, in his opinion, was his best friend and the most brilliant woman in the world. The letter was in French, and ran as follows :

“Dear Aunty : — I have made a resolution on which the fate of my whole life must depend. I will leave the university in order to devote myself to country life, because I feel that I was born for it. For God’s sake, dear aunty, do not laugh at me! You will say that I am young; and, indeed, I may still be a child, but this does not prevent me from feeling what my calling is, and from wishing to do good, and loving it.

“As I have written you before, I found affairs in an indescribable disorder. Wishing to straighten them out, and to understand them, I discovered that the main evil lay in the most pitiable, poverty-stricken condition of the peasants, and that the evil was such that it could be mended by labour and patience alone. If you could only see two of my peasants, David and Ivan, and the lives which they lead with their families, I am sure that the mere sight of these unfortunates would convince you more than all I might say to explain my intention to you.

“Is it not my sacred and direct duty to care for the welfare of these seven hundred men, for whom I shall be held responsible before God? Is it not a sin to abandon them to the arbitrariness of rude elders and managers, for plans of enjoyment and ambition? And why should I look in another sphere for opportunities of being useful and doing good, when such a noble, brilliant, and immediate duty is open to me?

“I feel myself capable of being a good landed proprietor; and, in order to be one, as I understand this word, one needs neither a university diploma, nor ranks, which you are so anxious I should obtain. Dear aunty, make no ambitious plans for me! Accustom yourself to the thought that I have chosen an entirely different path, which is, nevertheless, good, and which, I feel, will bring me happiness. I have thought much, very much, about my future duty, have written out rules for my actions, and, if God will only grant me life and strength, shall succeed in my undertaking.

“Do not show this letter to my brother Vasya. I am afraid of his ridicule; he is in the habit of directing me, and I of submitting to him. Vanya will understand my intention, even though he may not approve of it.”

The countess answered with the following French letter

“Your letter, dear Dmitri, proved nothing to me, except that you have a beautiful soul, which fact I have never doubted. But, dear friend, our good qualities do us more harm in life than our bad ones. I will not tell you that you are committing a folly, and that your con-duct mortifies me; I will try to influence you by argu-ments alone. Let us reason, my friend. You say that you feel a calling for country life, that you wish to make your peasants happy, and that you hope to be a good pro-prietor.

(1) I must tell you that we feel a calling only after we have made a mistake in it;

(2) that it is easier to make yourself happy than others; and

(3) that in order to be a good proprietor, one must be a cold and severe man, which you will scarcely be, however much you may try to dissemble.

“You consider your reflections incontrovertible, and even accept them as rules of conduct; but at my age, my dear, we do not believe in reflections and rules, but only in experience; and experience tells me that your plans are childish. I am not far from fifty, and I have known many worthy people, but I have never heard of a young man of good family and of ability burying himself in the country, for the sake of doing good. You always wished to appear original, but your originality is nothing but superfluous self-love. And, my dear, you had better choose well-trodden paths!

They lead more easily to success, and success, though you may not need it as suc-cess, is necessary in order to have the possibility of doing the good which you wish.

“The poverty of a few peasants is a necessary evil, or an evil which may be remedied without forgetting all your obhgations to society, to your relatives, and to your-self. With your intellect, with your heart and love of virtue, there is not a career in which you would not obtain success; but at least choose one which would be worthy of you and would do you honour.

“I believe in your sincerity, when you say that you have no ambition; but you are deceiving yourself.

Ambition is a virtue at your years and with your means; but it becomes a defect and a vulgarity, when a man is no longer able to satisfy that passion. You, too, will experience it, if you will not be false to your intention. Good-bye, dear Mitya! It seems to me that I love you even more for your insipid, but noble and magnanimous, plan. Do as you think best, but I confess I cannot agree with you.”

Having received this letter, the young man long meditated over it; finally, having decided that even a brilliant woman may make mistakes, he petitioned for a discharge from the university, and for ever remained in the country.

II

THE YOUNG PROPRIETOR, as he wrote to his aunt, had formed rules of action for his estate, and all his life and occupations were scheduled by hours, days, and months. Sunday was appointed for the reception of petitioners, domestic and manorial serfs, for the inspection of the farms of the needy peasants, and for the distribution of supplies with the consent of the Commune, which met every Sunday evening, and was to decide what aid each was to receive. More than a year passed in these occu-pations, and the young man was not entirely a novice, either in the practical or in the theoretical knowledge of farming.

It was a clear June Sunday when Nekhlyudov, after drinking his coffee, and running through a chapter of “Maison Eustique,” with a note-book and a package of bills in the pocket of his light overcoat, walked out of the large, columnated, and terraced country-house, in which he occupied a small room on the lower story, and directed his way, over the neglected, weed-grown paths of the old English garden, to the village that was situated on both sides of the highway. Nekhlyudov was a tall, slender young man with long, thick, wavy, auburn hair, with a bright sparkle in his black eyes, with red cheeks, and ruby lips over which the first down of youth was just appearing.

In all his movements and in his gait were to be seen strength, energy, and the good-natured self-satisfaction of youth. The peasants were returning in variegated crowds from church; old men, girls, children, women with their suckling babes, in gala attire, were scattering to their huts, bowing low to their master, and making a circuit around him. When Nekhlyudov reached the street, he stopped, drew his note-book from his pocket, and on the last page, which was covered with a childish handwriting, read several peasant names, with notes. “Ivan Churis asked for fork posts,” he read, and, proceeding in the street, walked up to the gate of the second hut on the right.

Churis’s dwelling consisted of a half-rotten log square, musty at the corners, bending to one side, and so sunken in the ground that one broken, red, shding window, with its battered shutter, and another smaller window, stopped up with a bundle of flax, were to be seen right over the dung-heap. A plank vestibule, with a decayed threshold and low door; another smaller square, more rickety and lower than the vestibule; a gate, and a wicker shed clung to the main hut. All that had at one time been covered by one uneven thatch; but now the black, rotting straw hung only over the eaves, so that in places the framework and the rafters could be seen.

In front of the yard was a well, with a dilapidated box, with a remnant of a post and wheel, and a dirty puddle made by the tramping of the cattle, in which some ducks were splashing. Near the well stood two ancient, cracked, and broken willows, with scanty, pale green leaves. Under one of these willows, which witnessed to the fact that at some time in the past some one had tried to beautify