The Decembrists, Decembrists, Leo Tolstoy

The Decembrists

Contents

FIRST FRAGMENT

I

II

III

SECOND FRAGMENT

THIRD FRAGMENT

FIRST FRAGMENT

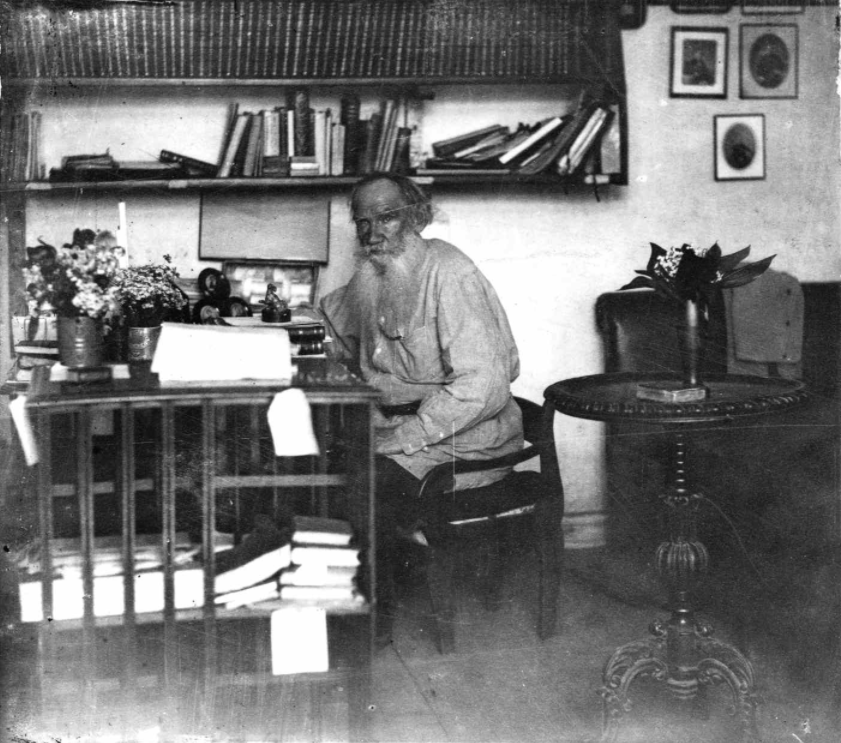

I

THE THREE chapters of the romance here printed under the name of the “Dekabristui “were written even before the author had begun “War and Peace.” At this time he was planning a story, the principal characters of which were to be the conspirators who planned the December Insur-rection; but he did not go on with it because, in his efforts at bringing to life the time of the Dekabrists, he involuntarily went back in thought to the preceding time period, to the past of his heroes. Gradually before the author opened ever deeper and deeper the sources of those phenomena which he was designing to describe : the families, the education, the social conditions, etc., of his chosen characters. At last he paused at the time of the war with Napoleon, which he described in “War and Peace.” At the end of that romance are evident the symptoms of that awakening which was reflected in the events of December 27, 1825.

Afterward the author once more took up “The Dekabrists,” and wrote two other beginnings, which are here printed.

IT happened not long ago, in the reign of the Emperor Alexander II., in our epoch of civilization, of progress, of questions, of the regeneration of Russia, etc., the time when the victorious Russian army had returned from Sevastopol, which had just been sur-rendered to the enemy, when all Russia was celebrat-ing its triumph in the destruction of the Black Sea fleet, and White-walled Moscow had gone forth to meet and congratulate the remains of the crews of that fleet, and reach them a good Russian glass of vodka, and in accordance with the good Russian custom offer them the bread and salt of hospitality, 2 and bow their heads to the ground; at the time when Russia in the person of perspicacious virgin-politicians bewailed the destruction of its favorite dreams about celebrating the Te Deum in the cathedral of Saint Sophia and the severely felt loss of two great men dear to the father-land, who had been killed during the war (one carried away by his desire to hear the Te Deum as soon as possible in the said cathedral and who fell on the plains of Vallachia, for that very reason leaving two squadrons of hussars on those same plains; the other an invaluable man distributing tea, other people’s money, and sheets to the wounded, and not stealing either); at the time when from all sides, from all branches of human activity, in Russia, great men sprang up like mushrooms colonels, administrators, econo-mists, writers, orators, and simply great men, without any vocation or object; at the time when at the jubilee of a Moscow actor, public sentiment, strengthened by a toast, began to demand the punishment of all criminals; when formidable committees from Petersburg were gal-loping away toward the south, to apprehend, discover, and punish the evil-doers of the commissary depart-ment; when in all the cities, dinners with speeches were given to the heroes of Sevastopol, and these men who came with amputated arms and legs were given trifles as remembrances, and they were met on bridges and highways; at the time when oratorical talents were so rapidly spreading among the people that a single tapster everywhere and on every occasion wrote and printed, and, having learned by heart, made at dinners such powerful addresses that the keepers of order had, as a general thing, to employ repressive measures against the eloquence of the tapster; when in the Eng-lish club itself they reserved a special room for the dis-cussion of public affairs; when new periodicals made their appearance under the most diversified appellations journals developing European principles on a Euro-pean soil, but with a Russian point of view, and journals exclusively on Russian soil developing Russian princi-ples, but with a European point of view; when suddenly so many periodicals appeared that it seemed as if all names were exhausted the Viestnik (Messenger), and the Slovo (Word), and the Besyeda (Discussion), and the Nabliudatyel (Spectator), and the Zvezda (Star), and the Orel (Eagle), and many others and notwithstand-ing this, new ones and ever new ones kept appearing; a time when pleiads of writers and thinkers kept appear-ing, proving that science is popular, and is not popular, and is unpopular, and the like, and a pleiad of writer-artists, describing the grove and the sunrise and the thunder-storm and the love of the Russian maiden and the laziness of a single chinovnik and the bad behavior of many other functionaries; at the time when from all sides came up questions as in 1856 they called all those currents of circumstances to which no one could obtain a categorical answer questions of military schools, 1 of uni-versities, of the censorship, of verbal law-proceedings re-lating to finance, banks, police, emancipation, and many others, and all were trying to raise still new questions, all were giving experimental answers to them, were writing, reading, talking, arranging projects, all the time wish-ing to correct, to annihilate, to change, and all the Rus-sians, as one man, found themselves in indescribable enthusiasm, a state of things which has been wit-nessed twice in Russia during the nineteenth century the first time when in 1812 we thrashed Napoleon I., and the second time when in 1856 Napoleon III. thrashed us great and never-to-be-forgotten epoch of the re-generation of the Russian people. Like that French-man, who said that no one had ever lived at all who had not lived during the great French Revolution, so I also do not hesitate to say that any one who was not living in Russia in the year ‘56 does not know what life is.

He who writes these lines not only lived at that time, but was actively at work then. Moreover, he himself stayed in one of the trenches before Sevastopol for sev-eral weeks. He wrote about the Crimean war a work which brought him great fame, and in this he clearly and circumstantially described how the soldiers fired their guns from the bastions, how wounds were bandaged at the ambulance stations, and how the dead were buried in the graveyard. Having accomplished these exploits, the writer of these lines spent some time at the heart of the empire, in a rocket establishment, where he received his laurels for his exploits. He saw the enthusiasm of both capitals and of the whole people, and he experi-enced in himself how Russia was able to reward genuine service. The powerful ones of that world all sought his acquaintance, shook hands with him, gave him din-’ ners, kept inviting him out, and, in order to elicit from him the particulars of the war, told him their own sen-timents. Consequently the writer of these lines may well appreciate that great unforgetable epoch.

But that does not concern us now.

One evening about this time two conveyances and a sledge were standing at the entrance of the best hotel in Moscow. A young man was just going in to inquire about rooms. An old man was sitting in one of the car-riages with two ladies, and was discussing about the Kuznetsky Bridge at the time of the French Invasion.

It was the continuation of a conversation which had been begun on their first arrival at Moscow, and now the old, white-bearded man, with his fur shuba thrown open, was calmly going on with it, still sitting in the carriage, as if he intended to spend the night there. His wife and daughter listened to him, but kept looking at the door, not without impatience. The young man came out again accompanied by the Swiss and the hall-boy.

“Well, how is it, Sergye’f? “asked the mother, looking out so that the lamplight fell on her weary face.

Either because it was his usual custom, or to prevent the Swiss from mistaking him for a lackey, as he was dressed in a half-shuba, Sergyei’ replied in French that they could have rooms, and he opened the carriage door. The old man for an instant glanced at his son, and fell back once mere into the dark depths of the carriage, as if this affair did not concern him at all.

“There was no theater then.”

“Pierre,” said his wife, pulling him by the cloak, but he continued :

“Madame Chalme was on the Tverskaya ….”

From the depths of the carriage rang out a young, merry laugh.

“Papa, come, you are talking nonsense.”

The old man seemed at last to realize that they had reached their destination, and he looked round.

“Come, step out.”

He pulled his hat over his eyes and obediently got out of the carriage. The Swiss offered him his arm, but, convinced that the old man was perfectly able to take care of himself, he immediately proffered his ser-vices to the elder lady.

Natalya Nikolayevna, the lady, by her sable cloak, and by the slowness of her motions in getting out, and by the way in which she leaned heavily on his arm, and by the way in which, without hesitation, she immediately took her son’s arm and walked up the steps, impressed the man as a woman of great distinction. He could not distinguish the young woman from the maids that dis-mounted from the second carriage; she, just as they, carried a bundle and a pipe, and walked behind. Only by her laughing, and the fact that she called the old man “father,” did he know it.

“Not that way, papa, turn to the right,” said she, detaining him by the sleeve ‘of his coat. “To the right.”

And on the stairway, above the stamping of