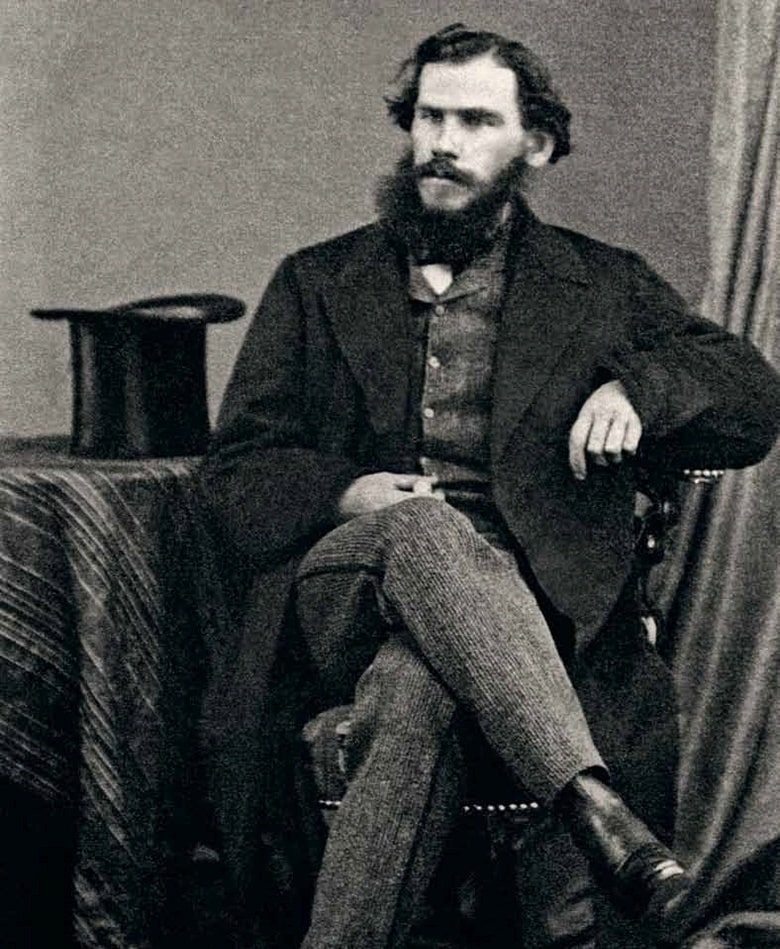

Diary Of A Lunatic, Leo Tolstoy

Diary Of A Lunatic

Translated by Constance Garnett 1912

THIS MORNING I underwent a medical examination in the government council room. The opinions of the doctors were divided. They argued among themselves and came at last to the conclusion that I was not mad. But this was due to the fact that I tried hard during the examination not to give myself away.

I was afraid of being sent to the lunatic asylum, where I would not be able to go on with the mad undertaking I have on my hands. They pronounced me subject to fits of excitement, and something else, too, but nevertheless of sound mind.

The doctor prescribed a certain treatment, and assured me that by following his directions my trouble would completely disappear. Imagine, all that torments me disappearing completely! Oh, there is nothing I would not give to be free from my trouble. The suffering is too great!

I am going to tell explicitly how I came to undergo that examination; how I went mad, and how my madness was revealed to the outside world.

Up to the age of thirty-five I lived like the rest of the world, and nobody had noticed any peculiarities in me. Only in my early childhood, before I was ten, I had occasionally been in a mental state similar to the present one, and then only at intervals, whereas now I am continually conscious of it.

I remember going to bed one evening, when I was a child of five or six. Nurse Euprasia, a tall, lean woman in a brown dress, with a double chin, was undressing me, and was just lifting me up to put me into bed.

“I will get into bed myself,” I said, preparing to step over the net at the bedside.

“Lie down, Fedinka. You see, Mitinka is already lying quite still,” she said, pointing with her head to my brother in his bed.

I jumped into my bed still holding nurse’s hand in mine. Then I let it go, stretched my legs under the blanket and wrapped myself up. I felt so nice and warm! I grew silent all of a sudden and began thinking: “I love nurse, nurse loves me and Mitinka, I love Mitinka too, and he loves me and nurse.

And nurse loves Taras; I love Taras too, and so does Mitinka. And Taras loves me and nurse. And mother loves me and nurse, nurse loves mother and me and father; everybody loves everybody, and everybody is happy.”

Suddenly the housekeeper rushed in and began to shout in an angry voice something about a sugar basin she could not find. Nurse got cross and said she did not take it. I felt frightened; it was all so strange. A cold horror came over me, and I hid myself under the blanket. But I felt no better in the darkness under the blanket. I thought of a boy who had got a thrashing one day in my presence-of his screams, and of the cruel face of Foka when he was beating the boy.

“Then you won’t do it any more; you won’t!” he repeated and went on beating.

“I won’t,” said the boy; and Foka kept on repeating over and over, “You won’t, you won’t!” and did not cease to strike the boy.

That was when my madness came over me for the first time. I burst into sobs, and they could not quiet me for a long while. The tears and despair of that day were the first signs of my present trouble.

I well remember the second time my madness seized me. It was when aunt was telling us about Christ. She told His story and got up to leave the room. But we held her back: “Tell us more about Jesus Christ!” we said.

“I must go,” she replied.

“No, tell us more, please!” Mitinka insisted, and she repeated all she had said before. She told us how they crucified Him, how they beat and martyred Him, and how He went on praying and did not blame them.

“Auntie, why did they torture Him?”

“They were wicked.”

“But wasn’t he God?”

“Be still-it is nine o’clock, don’t you hear the clock striking?”

“Why did they beat Him? He had forgiven them. Then why did they hit Him? Did it hurt Him? Auntie, did it hurt?”

“Be quiet, I say. I am going to the dining-room to have tea now.”

“But perhaps it never happened, perhaps He was not beaten by them?”

“I am going.”

“No, Auntie, don’t go!…” And again my madness took possession of me. I sobbed and sobbed, and began knocking my head against the wall.

Such had been the fits of my madness in my childhood. But after I was fourteen, from the time the instincts of sex awoke and I began to give way to vice, my madness seemed to have passed, and I was a boy like other boys.

Just as happens with all of us who are brought up on rich, over-abundant food, and are spoiled and made effeminate, because we never do any physical work, and are surrounded by all possible temptations, which excite our sensual nature when in the company of other children similarly spoiled, so I had been taught vice by other boys of my age and I indulged in it.

As time passed other vices came to take the place of the first. I began to know women, and so I went on living, up to the time I was thirty-five, looking out for all kinds of pleasures and enjoying them. I had a perfectly sound mind then, and never a sign of madness.

Those twenty years of my normal life passed without leaving any special record on my memory, and now it is only with a great effort of mind and with utter disgust, that I can concentrate my thoughts upon that time.

Like all the boys of my set, who were of sound mind, I entered school, passed on to the university and went through a course of law studies. Then I entered the State service for a short time, married, and settled down in the country, educating-if our way of bringing up children can be called educating-my children, looking after the land, and filling the post of a Justice of the Peace.

It was when I had been married ten years that one of those attacks of madness I suffered from in my childhood made its appearance again. My wife and I had saved up money from her inheritance and from some Government bonds of mind which I had sold, and we decided that with that money we would buy another estate. I was naturally keen to increase our fortune, and to do it in the shrewdest way, better than any one else would manage it.

I went about inquiring what estates were to be sold, and used to read all the advertisements in the papers. What I wanted was to buy an estate, the produce or timber of which would cover the cost of purchase, and then I would have the estate practically for nothing. I was looking out for a fool who did not understand business, and there came a day when I thought I had found one. An estate with large forests attached to it was to be sold in the Pensa Government.

To judge by the information I had received the proprietor of that estate was exactly the imbecile I wanted, and I might expect the forests to cover the price asked for the whole estate. I got my things ready and was soon on my way to the estate I wished to inspect.

We had first to go by train (I had taken my man-servant with me), then by coach, with relays of horses at the various stations. The journey was very pleasant, and my servant, a good-natured youth, liked it as much as I did. We enjoyed the new surroundings and the new people, and having now only about two hundred miles more to drive, we decided to go on without stopping, except to change horses at the stations. Night came on and we were still driving.

I had been dozing, but presently I awoke, seized with a sudden fear. As often happens in such a case, I was so excited that I was thoroughly awake and it seemed as if sleep were gone for ever. “Why am I driving? Where am I going?” I suddenly asked myself. It was not that I disliked the idea of buying an estate at a bargain, but it seemed at that moment so senseless to journey to such a far away place, and I had a feeling as if I were going to die there, away from home. I was overcome with terror.

My servant Sergius awoke, and I took advantage of the fact to talk to him. I began to remark upon the scenery around us; he had also a good deal to say, of the people at home, of the pleasure of the journey, and it seemed strange to me that he could talk so gaily. He appeared so pleased with everything and in such good spirits, whereas I was annoyed with it all. Still, I felt more at ease when I was talking with him. Along with my feelings of restlessness and my secret horror, however, I was fatigued as well, and longed to break the journey somewhere. It seemed to me my uneasiness would cease if I could only enter a room, have tea, and, what I desired most of all, sleep.

We were approaching the town Arzamas.

“Don’t you think we had better stop here and have a rest?”

“Why not? It’s an excellent