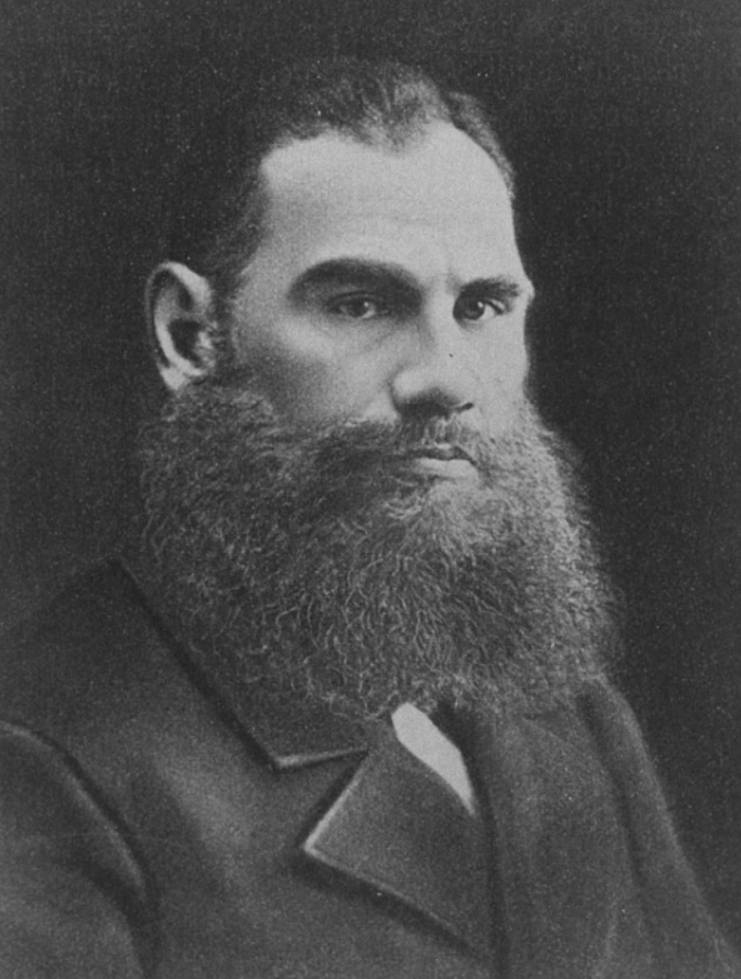

Stories Of My Dogs, Leo Tolstoy

Stories Of My Dogs

Translated by Nathan Haskell Dole 1888

Chapter I BULKA

I HAD a bulldog, and his name was Bulka. He was perfectly black, except for the paws of his fore legs, which were white. All bulldogs have the lower jaw longer than the upper, and the upper teeth set into the lower; but in the case of Bulka the lower jaw was pushed so far forward that the finger could be inserted between the upper and lower teeth.

Bulka had a broad face and big, black, brilliant eyes. And his teeth and white tusks were always uncovered. He was like a negro.

Bulka had a gentle disposition and he would not bite; but he was very powerful and tenacious. Whenever he took hold of anything, he set his teeth together and hung on like a rag, and it was impossible to make him let go; he was like a pair of pincers.

One time he was set on a bear, and he seized the bear by the ear, and hung on like a bloodsucker. The bear pounded him with his paws, hugged him, shook him from side to side, but he could not get rid of him; then he stood on his head in his attempts to crush him, but Bulka hung on until they could dash cold water over him.

I took him when he was a puppy, and reared him myself. When I went to the Caucasus, I did not care to take him with me, and I went away noiselessly, and gave orders to keep him chained up.

At the first post-station I was just going to start off with a fresh team, when suddenly I saw something black and bright dashing along the road.

It was Bulka in his brass collar. He flew with all his might toward the station. He leaped up on me, licked my hand, and then stretched himself out in the shadow of the telyega. His tongue lolled out at full length. He kept drawing it back, swallowing the spittle, and then thrusting it out again. He was all panting; he could not get his breath; his sides actually labored. He twisted from side to side, and pounded the ground with his tail.

I learned afterward that, when he found I had gone, he broke his chain, and jumped out of the window, and dashed over the road after my trail, and had thus run twenty versts in the heat of the day.

Chapter II BULKA AND THE WILD BOAR

ONE time in the Caucasus we went boar hunting, and Bulka ran to go with me. As soon as the boar-hounds got to work, Bulka dashed off in the direction of their music and disappeared in the woods.

This was in the month of November; at that time the wild boars and pigs are usually very fat. In the forests of the Caucasus, frequented by wild boars, grow all man-ner of fruits, wild grapes, cones, apples, pears, black-berries, acorns, and rose-apples. And when all these fruits get ripe, and the frost loosens them, the wild swine feed on them and fatten.

At this time of the year the wild boar becomes so fat that he cannot run far when pursued by the dogs. When they have chased him for two hours, he strikes into a thicket and comes to bay there.

Then the hunters run to the place where he is at bay and shoot him. By the barking of the dogs one can tell whether the boar has taken to cover or is still running. If he is running, then the dogs bark with a yelp, as if some one were beating them; but if he has taken to cover, then they bay with a long howl, as if at a man.

In this expedition I had been running a long time through the forest, but without once coming across the track of a boar. At last I heard the protracted howl and whine of the hounds, and I turned my steps in that direction.

I was already near the boar. I could hear a crashing in the thicket. This was made by the boar, pursued by the dogs. But I could tell by their barking that they had not yet brought him to bay, but were only chasing around him.

Suddenly I heard something rushing behind me, and looking around, I saw Bulka. He had evidently lost track of the boar-hounds in the forest, and had become confused; but now he had heard their baying, and also, like myself, was in full tilt in their direction.

He was running across a clearing through the tall grass, and all I could see of him was his black head, and his tongue lolling out between his white teeth.

I called him, but he did not look around; he dashed by me, and was lost to sight in the thicket. I hurried after him, but the farther I went, the denser became the underbrush. The branches knocked off my hat and whipped my face; the thorns of the briers clutched my coat. By this time I was very near the barking dogs, but I could not see anything.

Suddenly I heard the dogs barking louder; there was a tremendous crash, and the boar, which was trying to break his way through, began to squeal. And this made me think that now Bulka had reached the scene and was attacking him.

I put forth all my strength, and made my way through the underbrush to the spot.

Here, in the very thickest of the woods, I caught a glimpse of a spotted boar-hound. He was barking and howling without stirring from one spot. Three paces from him I saw something black struggling.

When I came nearer I perceived that it was the boar, and I heard Bulka whining piteously. The boar was grunting and charging the hound, which, with his tail between his legs, was backing away from him. I had a fair shot at the side and the head of the boar. I aimed at his side and fired; I could see that my shot took effect. The boar uttered a squeal, and turning from me dashed into the thicket. The dogs ran bark-ing and yelping on his trail. I broke my way through the thicket after them.

Suddenly I heard and saw something under my very feet. It was Bulka. He was lying on his side and whining. Under him was a pool of blood. I said to myself, “ My dog is ruined; “ but now I had something else to attend to, and I rushed on.

Soon I saw the boar. The dogs were attacking him from behind, and he was snapping first to one side, then to the other. When the boar saw me, he made a dash at me. I fired for the second time, with the gun almost touching him, so that his bristles were singed. The boar gave one last grunt, stumbled, and fell with all his weight on the ground.

When I reached him, he was already dead; only here and there his body twitched, or purled up a little.

But the dogs, with bristling hair, were tearing at his belly and his legs, and others were licking the blood from where he was wounded.

That reminded me of Bulka, and I hastened back to find him. He crawled to meet me, and groaned. I went to him, knelt down, and examined his wound. His belly was torn open, and a whole mass of his bowels protruded and lay upon the dry leaves.

When my comrades joined me, we replaced Bulka’s intestines, and sewed up his belly. While we were sew-ing up his belly and puncturing the skin, he kept lick-ing my hand.

They fastened the boar to a horse’s tail, so as to bring it from the woods, and we put Bulka on a horse’s back, and thus we brought him home. Bulka was an invalid for six weeks, but he got well at last.

Chapter III PHEASANTS

IN the Caucasus woodcock are called fazamii, or pheasants. They are so abundant that they are cheaper than domestic fowl. Pheasants are hunted with the kobuilka} with the podsada, or by means of the dog.

This is the method of hunting with the kobuilka : You take canvas and stretch it over a frame; in the middle of the frame you put a joist, and make a hole in the canvas. This canvas-covered frame is called a kobuilka. With this kobuilka and a gun you go out into the forest just after sunrise. You carry the kobuilka in front of you, and through the hole you keep a lookout for pheasants. The pheasants in the early morning go out in search of food. Sometimes you come across a whole family; sometimes the hen with the chicks; sometimes the cock with his hen; sometimes several cocks together.

The pheasants see no man, and they are not afraid of the canvas, and they let any one approach very near. Then the hunter sets down his kobuilka, puts the muzzle of his musket out through the hole, and shoots at his leisure.

The following is the method of hunting with the podsada: You let loose in the woods a little common house-dog, and follow after him. When the dog starts up a pheasant, he chases it. The pheasant flies into a tree, and then the whelp begins to yelp. The hunts-man goes in the direction of the barking, and shoots the pheasant in the tree.

This mode of hunting would be easy if the pheasant would fly into an isolated tree, or would sit on an exposed branch so as to be