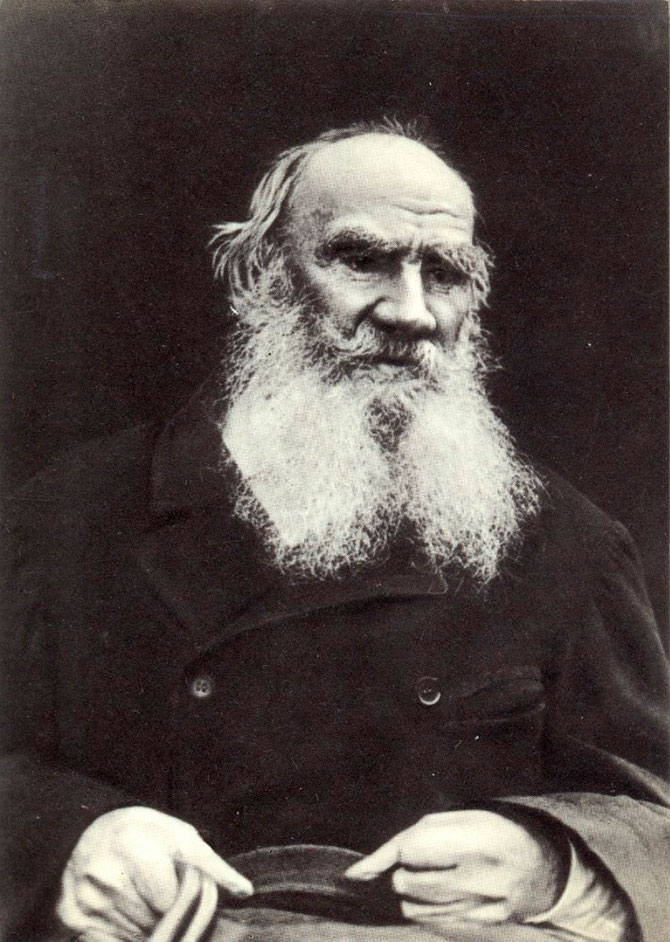

What Then Must We Do? Leo Tolstoy

What Then Must We Do?

Translated by Aylmer Maude 1886

CHAPTER I

I HAD spent my life in the country, and when in 1881 I came to live in Moscow the sight of town poverty surprised me. I knew country poverty, but town poverty was new and incomprehensible to me. In Moscow one cannot pass a street without meeting beggars, and beggars who are not like those in the country. They do not ‘carry a bag and beg in Christ’s name’, as country beggars say of themselves; they go without a bag and do not beg.

When you meet or pass them they generally only try to catch your eye; and according to your look they either ask or do not ask. I know one such beggar from among the gentry. The old man walks slowly, stooping at each step. When he meets you he stoops on one leg and seems to be making you a bow. If you stop he takes off his cockaded cap, bows again, and begs; but if you do not stop he makes as though this were merely his way of walking, and goes on, bowing in the same way on the other leg. He is a typical educated Moscow beggar. At first I did not know why they do not ask plainly. Afterwards I learnt this but still did not understand their position.

Once, passing through the Afanasev side-street, I saw a policeman putting a ragged peasant who was swollen with dropsy, into an open cab. I asked: ‘What is this for?’ The policeman replied: ‘For begging.’ ‘Is that forbidden?’ ‘It seems it’s forbidden!’ replied the policeman.

The man with dropsy was taken away in the cab. I got into another cab and followed them. I wanted to find out whether it was really forbidden to ask alms and in what way it was repressed. I could not at all understand that it should be possible to forbid a man s asking another man for anything; and also I could not believe that asking alms was forbidden, for Moscow was full of beggars. I entered the police station to which the beggar was taken. There a man who had a sword and a pistol was sitting at a table. I asked: ‘What has that peasant been arrested for?’ The man with the sword and pistol looked at me sternly and said: ‘What business is it of yours?’

Feeling however that he ought to explain something to me, he added: ‘The authorities order such people to be arrested, so it has to be done.’ I went out. The policeman who had brought the beggar in was sitting o~ a windowsill in the entrance-hall looking dejectedly at a note-book. I asked him: ‘Is it true that beggars are forbidden to ask in Christ’s name for alms?’ The policeman roused himself, looked up at me, and then did not exactly frown but seemed to drowse off again, and sitting on the window-.sill said: ‘The authorities order it, so that means it’s necessary’; and he occupied himself again with his note-book. I went out into the porch to the cabman.

‘Well, what’s happened? Have they arrested him?’ asked the cabman. He, too, was evidently interested in this affair. .

‘They have,’ I replied. The cabman shook his head disapprovingly.

‘How is it that it is forbidden, in this Moscow of yours, to ask alms in Christ’s name?’ I inquired.

‘Who knows?’ said the cabman.

‘How is it?’ I said. ‘The destitute are Christ’s folk, yet they take this man to a police-station.’ ‘Nowadays that is the law. Begging is not allowed.’

After that I several times saw how the police took beggars to a police-station and afterwards to the Usupov workhouse. Once, on the Myasnitski street, I met a crowd of these beggars, some thirty of them. In front and behind went policemen. I asked: ‘What is it for?’ ‘For asking alms.’

It turned out that in Moscow, by law, all the beggars (of whom one meets several in every street, and rows of whom stand outside every church when service is on, and who regularly attend every funeral) are forbidden to beg.

But why some are caught and shut up and others not, I was never able to understand. Either there are among them some legal and some illegal beggars, or there are so many that they cannot all be caught, or else as quickly as some are captured others appear.

There are in Moscow beggars of all sorts.

There are some who live by it, and there are genuine beggars who have come to Moscow for some reason or other and are really destitute.

Among these latter there are many simple peasants, both men and women, wearing peasant clothes. I often meet them. Some of them have fallen ill here and have come out of hospital and can neither support themselves nor get away from Moscow. Some of them have also taken to drink (as no doubt had the man who was ill with dropsy); some are not ill but have lost their all in a fire, or are old, or-are women with children; while some are quite healthy and capable of working.

These quite healthy peasants, asking alms, interested me particularly; for since I came to Moscow I had for the sake of exercise formed the habit of going to work at the Sparrow Hills with two peasants who sawed wood there. These two men were just like those I met in the streets. One was Peter, a soldier from Kaluga; the other was Semen, a peasant from Vladimir. They owned nothing but the clothes on their backs and their own hands. With those hands by working very hard they earned 40 to 45 kopeks (10d. to 11d.) a day, of which they both put something by: Peter, to buy a sheepskin coat, and Semen, for the journey back to his village. For this reason I was particularly interested in such people when I met them in the streets.

Why do these work and those beg?

On meeting such a peasant I generally asked how he came to be in such a state. I once met a healthy peasant whose beard was beginning to go grey. He begged. I asked who he was and where he was from. He said he had come from Kaluga to find work. At first he had found some work cutting up old timber for firewood. He and his mate cut up all the wood at one place. Then he looked for another job but found none. His mate left him, and now he had been knocking about for a fortnight having eaten all he possessed, and he had nothing with which to buy either a saw or an axe. I gave him money for a saw and told him where he could come and work. (I had arranged beforehand with Peter and Semen to take on another man and to find him a mate.)

‘Well then, be sure and come. There is plenty of work there,’ said I.

‘I’ll come of course I’ll come. Does one like to go begging?’ said he. ‘I can work.’

He swore he would come, and it seemed to me he was in earnest and meant to.

Next day I joined my acquaintances the peasants and asked if the man had turned up. He had not. And several others deceived me in the same way. I was also cheated by men who

said they only needed money to buy a railway ticket home, but whom I met on the street again a week later. Many such I recognized and they recognized me; but sometimes, having forgotten me, they told me the same story again. Some of them turned away on seeing me. So I learned that among this class too there are many cheats; but I was very sorry for these cheats; they were a half-clad, poor, thin, sickly folk: the kind of people who really freeze to death or hang themselves, as we learn from the papers.

CHAPTER II

WHEN I spoke to Moscovites of this destitution in the city I was always told, ‘Oh, what you have seen is nothing! Go to Khitrov market and see the dosshouses there. That’s where you’ll see the real “Golden Company”!’

One jester told me it was no longer a ‘Company’, but had become a ‘Golden Regiment’-there are now so many of them. The jester was right; but he would have been still more so had he said that in Moscow these people are now neither a company nor a regiment but a whole army numbering, I suppose, about 50,000. Old inhabitants when telling me of town poverty always spoke of it with a kind of pleasure-as if proud of knowing about it.

I remember also that when I was in London, people there spoke boastfully of London pauperism: ‘Just look what it is like here!’ .

I wanted to see this destitution about which I had been told, and several times I set out towards Khitrov market, but each time I felt uncomfortable and ashamed. ‘Why go to look at the sufferings of people I cannot help?’ said one voice within me: ‘If you live here and see all the allurements of town-life, go and see that also,’ said another voice; and so one frosty windy day in December 1881, I went to the heart of the town destitution-Khitrov market.

It was a week-day, towards four o’clock. In Solyanka Street I already noticed more and more people wearing strange clothes not made for them, and yet stranger footgear; people with a peculiar, unhealthy complexion, and especially with an air, common to them all,