The French revolution, the July revolution of 1830, the revolution of 1848, the American Civil War of the 1860s, the Russian Revolution of 1905 and the Russian Revolution of 1917 – all pushed Britain’s social development ahead and set the landmarks of major legislative reforms in her history. Without the Russian Revolution of 1917, MacDonald would never have been prime minister in 1924. Of course we do not mean by this that MacDonald’s ministry was the highest conquest of October. But it was at all events largely its by-product.

And even children’s picture-books teach us that if you want to have acorns you must not dig up the oak tree. Besides, how ridiculous is this Fabian conceit: since the Russian Revolution has taught “us” (who?) a lesson, then “we” (who?) shall settle things without revolution. But why then did the lessons of all previous wars not permit “you” to manage without the imperialist war?

In the same way that the bourgeoisie calls every successive war the last war. so MacDonald wants to call the Russian Revolution the last revolution. But why exactly should the British bourgeoisie make concessions to the British proletariat and peacefully, without a fight, renounce its property – merely because it has received in advance from MacDonald a firm assurance that, following the experience of the Russian revolution, British socialists shall never take the path of violence?

Where and when has the ruling class ever given up their power and property by a peaceful vote, least of all a class such as the British bourgeoisie, which has behind it centuries of world-wide plunder?

MacDonald is against revolution and for organic evolution: he carries over poorly digested biological concepts into society. For him revolution, as a sum of accumulated partial mutations, resembles the development of living organisms, the turning of a chrysalis into a butterfly and so forth; but in this latter process he ignores just those decisive, critical moments when the new creature bursts the old casing in a revolutionary way.

Here though it turns out that MacDonald is “for a revolution similar to that which took place in the womb of feudalism, when the industrial revolution carne to maturity”. MacDonald in his ignorance evidently imagines that the industrial revolution took place molecularly, without upheavals, calamities and devastation. He simply does not know Britain’s history (let alone the history of other countries); and above all he does not understand that the industrial revolution, which was already maturing in the womb of feudalism in the form of merchant capital, brought about the Reformation [4], caused the Stuarts to collide with parliament, gave birth to the Civil War and ruined and devastated Britain – in order afterwards to enrich her.

It would be tedious here to interpret the conversion of a chrysalis into a butterfly so as to establish the necessary social analogies. It is simpler and shorter to recommend MacDonald to ponder over the old comparison between a revolution and childbirth. Can we not draw a “lesson” here – since births produce “nothing” except pains and torment (the infant does not come into it!) then in future the population is recommended to multiply by painless Fabian means, with recourse to the talents of Mrs. Snowden as midwife.

Let us warn, however, that this is by no means so simple. Even the chick which has taken shape in the egg has to apply force to the calcareous prison that shuts it in; if some Fabian chick decided out of Christian (or any other) considerations to refrain from acts of force the calcareous casing would inevitably suffocate it. British pigeon fanciers are producing a special variety with a shorter and shorter beak, by artificial selection. There comes a time, however, when the new offspring’s beak is so short that the poor creature can no longer pierce the egg-shell: the young pigeon falls victim to compulsory restraint from violence; and the continued progress of the short-beaked variety comes to a halt. If our memory serves us right, MacDonald can read about this in Darwin.

Still pursuing these analogies with the organic world so beloved of MacDonald, we can say that the political art of the British bourgeoisie consists of shortening the proletariat’s revolutionary beak, thereby preventing it from perforating the shell of the capitalist state. The beak of the proletariat is its party. If you take a glance at MacDonald, Thomas and Mr. and Mrs. Snowden then it must be admitted that the bourgeoisie’s work of rearing the shortbeaked and soft-beaked varieties has been crowned with striking success – for not only are these worthies unfit to break through the capitalist shell, they are really unfit to do anything at all.

Here, however, the analogy ends, revealing all the limitations of such cursory data from biology textbooks in place of a study of the conditions and routes of historical development. Human society, although growing out of the organic and inorganic world, represents such a complex and concentrated combination of them that it requires an independent study.

A social organism is distinguished from a biological one by, amongst other things, a far greater flexibility and capacity for regrouping its elements, by a certain degree of conscious choice of its tools and devices, and by the conscious application (within certain limits) of the experience of the past, and so on. The pigeon chick in the egg cannot change its over-short beak and so it perishes. The working class when faced with the question of whether to be or not to be can sack MacDonald and Mrs. Snowden and arm itself with the “beak” of a revolutionary party for the destruction of the capitalist system.

Especially curious in MacDonald is the coupling of a crudely biological theory of society with an idealist Christian abhorrence of materialism. “You talk about revolution and a catastrophic leap but take a look at nature and see how intelligently a caterpillar behaves when it is due to turn into a chrysalis, take a look at the worthy tortoise in its motion, you will find the natural rhythm of the transformation of society.

Learn from nature!” And in this same vein MacDonald brands materialism “a banality, a nonsensical assertion, there is no spiritual or intellectual refinement in it …” MacDonald and refinement! Isn’t this indeed an astounding “refinement: seeking the model for man’s collective social activity in a caterpillar, while at the same time demanding for his private use an immortal soul with a comfortable existence in the hereafter?

“Socialists are accused of being poets. That is correct,” explains MacDonald, “we are poets. There cannot be good politics without poetry. And in general without poetry there can be nothing good.” And so on and so forth in the same style. And in conclusion: “The world needs more than anything some political and social Shakespeare.” This drivel about poetry may not be so obnoxious politically as lectures on the impermissibility of violence.

But MacDonald’s utter lack of intellectual talent is here expressed even more convincingly, if that is possible. A solemn, cowardly pedant, in whom there is as much poetry as in a square inch of carpet attempts to impress the world with Shakespearian grimaces. Here is where the “monkey-tricks” that MacDonald ascribes to the Bolsheviks really begin. MacDonald, as the “poet” of Fabianism! The politics of Sidney Webb as an artistic creation! Thomas’s ministry as the poetry of the colonies! And finally Mr. Snowden’s budget as the City of London’s song of love triumphant!

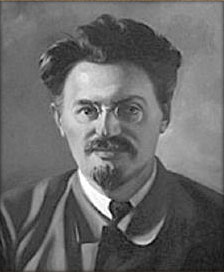

While drivelling about a social Shakespeare, MacDonald has overlooked Lenin. What a good thing for MacDonald, if not for Shakespeare, that the greatest English poet worked over three centuries ago: MacDonald has had sufficient time to see the Shakespeare in Shakespeare. He would never have recognized him had he been his contemporary. For MacDonald has overlooked – fully and completely overlooked – Lenin. Philistine blindness finds a dual expression: aimlessly sighing for Shakespeare, and ignoring his greatest contemporary.

“Socialism is interested in art and the classics.” It is amazing how this “poet” is able by his very touch to vulgarize an, idea in which there is, in itself, nothing vulgar. To be convinced of this it is enough to read his conclusion: “Even where great poverty and great unemployment exist as, unfortunately, they do in our country, the public must not begrudge the acquisition of pictures and in general anything that evokes ecstasy and elevates the spirit of young and old.”

It is not, however, altogether clear from this excellent advice whether the acquisition of pictures is recommended to the unemployed themselves – this would presuppose an appropriate supplementary grant for their need- or whether MacDonald is advising the high-minded ladies and gentlemen to purchase pictures “despite the unemployment” and thereby to “elevate their spirit”. We must assume that the second is closer to the truth.

But surely in that case we only see in front of us the liberal, drawing-room, Protestant clergyman who speaks a few tearful words about poverty and the “religion of conscience”, and then invites his worldly flock not to succumb completely to despondency but to continue their former way of life? After this let those who want to believe that materialism is vulgar, while MacDonald is a social poet yearning for Shakespeare. We consider that, if in the physical world there exists a degree of absolute cold, then in the spiritual world there must be a degree of absolute vulgarity