Vanity and egotism

Through the central framing device of the portrait and Dorian’s reaction to it, scholars have hinted that Wilde touches heavily on the themes of vanity and egotism within the work, through Dorian finding a medium to investigate both themes’ relevance to Victorian society. In chapter 3, Dorian’s upbringing is revealed. Dorian’s father “was a junior officer in the infantry, ‘a penniless fellow’… ‘a mere nobody’…” (Wilde 35).

According to scholar Richard J. Walker, Dorian’s upbringing makes his vanity seemingly a product of it. Walker follows this claim through by showing, in chapter 7, Dorian’s high taste. Dorian describes the east as a “Gothic creation with its ‘dimly-lit streets’ and ‘evil-looking houses'” inhabited by “‘women with horses voices,’ drunkards that curse and chatter ‘like monstrous apes’, and ‘grotesque children'” (Wilde 86/Walker 92). Walker, through this passage, makes the claim that Dorian’s vanity makes him see anything that he doesn’t have less than desirable.

Scholars have argued Dorian’s downward spiral does not start until the painter Basil Hallward is captivated by his charms. According to Aati Alaati, a scholar who delves into the themes of decadence and vanity in his own writings, “Basil thinks that art should be unconscious, ideal, and remote, but he shows an extreme degree of self-consciousness” (Alaati, 13). We see how prior to the book’s start Hallward’s influence bleeds into Dorian, an influence that becomes more prominent once Lord Henry warns Dorian about the beauty he would lose through aging. Dorian goes as far as to say that “youth is the only thing worth having. When I find that I am growing old, I shall kill myself” (Wilde, 28).

Through the influence of Lord Henry, Basil starts to notice how Lord Henry is molding Dorian Gray to living a corrupt double life. According to Dominic Mangianello, Dorian starts to believe that “sin no longer ravishes the beauty of the soul, as in the traditional view, but rather helps it to flourish”, therefore allowing him to validate doing whatever he pleases as long as it feels good (Manganiello 26). Due to Henry’s influence, Dorian becomes a self-centered and vain person, which ultimately becomes the reason for his fall into depravity.

Dorian acts on hedonism, which leads him to becoming self-destructive and corrupt. This is why his portrait rots as he sins. Sarah Kofman says in her book Enigmas that “Dorian’s soul, which has not yet lost its purity and innocence, becomes the object of desire for two men who want to attract it in opposite directions: one on whom he himself ‘exercises’ an influence but who has had no effect on him, the other who, by revealing the mystery of life to him, does indeed seize hold of his soul and makes devilish attempt to re-create him in his own image under the effect of his ‘bad influence'”(Kofman, 28).

Vanity is an overarching theme throughout the book. Dorian demonstrates his resentfulness towards things that would outlive his youth by saying “I am jealous of everything whose beauty does not die. I am jealous of the portrait you have painted of me” (Wilde, 28). In chapter 11, Dorian is under the influence of the “yellow book” that Lord Henry has lent him. Dorian studies beautiful objects, like jewels and music, held by those who came before him. Dorian becomes interested in various historical, philosophical figures, and Catholicism. He is interested with Catholicism for its aesthetic not for religious reasons. Dorian’s arguably superficial world view leads him to value the appearance of beauty over anything else. He watches his portrait because he is becoming “more and more enamored of his own beauty” (chapter xi, 124).

Influences and allusions

Wilde’s own life

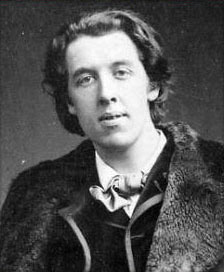

Wilde wrote in an 1894 letter:

The Picture of Dorian Gray contains much of me in it – Basil Hallward is what I think I am; Lord Henry, what the world thinks me; Dorian is what I would like to be – in other ages, perhaps.

Hallward is supposed to have been formed after painter Charles Haslewood Shannon. Scholars generally accept that Lord Henry is partly inspired by Wilde’s friend Lord Ronald Gower. It was purported that Wilde’s inspiration for Dorian Gray was the poet John Gray, but Gray distanced himself from the rumour. Some believe that Wilde used Robert de Montesquiou in creating Dorian Gray.

Faust

Wilde is purported to have said, “in every first novel the hero is the author as Christ or Faust.” In both the legend of Faust and in The Picture of Dorian Gray a temptation (ageless beauty) is placed before the protagonist, which he indulges. In each story, the protagonist entices a beautiful woman to love him, and then destroys her life. In the preface to the novel, Wilde said that the notion behind the tale is “old in the history of literature”, but was a thematic subject to which he had “given a new form”.

Unlike the academic Faust, the gentleman Dorian makes no deal with the Devil, who is represented by the cynical hedonist Lord Henry, who presents the temptation that will corrupt the virtue and innocence that Dorian possesses at the start of the story. Throughout, Lord Henry appears unaware of the effect of his actions upon the young man; and so frivolously advises Dorian, that “the only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it. Resist it, and your soul grows sick with longing.” As such, the devilish Lord Henry is “leading Dorian into an unholy pact, by manipulating his innocence and insecurity.”

Shakespeare

In the preface, Wilde speaks of the sub-human Caliban character from The Tempest. In chapter seven, when he goes to look for Sibyl but is instead met by her manager, he writes: “He felt as if he had come to look for Miranda and had been met by Caliban”.

When Dorian tells Lord Henry about his new love Sibyl Vane, he mentions the Shakespeare plays in which she has acted, and refers to her by the name of the heroine of each play. In the 1891 version, Dorian describes his portrait by quoting Hamlet, in which the eponymous character impels his potential suitor (Ophelia) to madness and possibly suicide, and Ophelia’s brother (Laertes) to swear mortal revenge.

Joris-Karl Huysmans

The anonymous “poisonous French novel” that leads Dorian to his fall is a thematic variant of À rebours (1884), by Joris-Karl Huysmans. In the biography Oscar Wilde (1989), the literary critic Richard Ellmann said:

Wilde does not name the book, but at his trial he conceded that it was, or almost was, Huysmans’s À rebours … to a correspondent, he wrote that he had played a “fantastic variation” upon À rebours, and someday must write it down. The references in Dorian Gray to specific chapters are deliberately inaccurate.

Possible Disraeli influence

Some commentators have suggested that The Picture of Dorian Gray was influenced by the British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli’s (anonymously published) first novel Vivian Grey (1826), as “a kind of homage from one outsider to another”. Part way through the book, which was serialised, Disraeli, in his capacity as the anonymous author, responds to criticism by readers of parts already published of “…the affectation, the flippancy, the arrogance, the wicked wit of this fictitious character” by explaining that he had “conceived of the character of a youth of great talents, whose mind had been corrupted…”.

He goes on to write: “To deem all things vain is the bitter portion of that mind, who, having known the world, dares to think.”. The name of Dorian Gray’s love interest, Sibyl Vane, may be a modified fusion of the title of Disraeli’s best known novel (Sybil) and Vivian Grey’s love interest Violet Fane, who, like Sibyl Vane, dies tragically. There is also a tale recounted within Vivian Grey in which the eyes in the portrait of a young man “…so beautiful…you cannot imagine…” move when its subject dies.

Reactions

Contemporary response

Even after the removal of controversial text, The Picture of Dorian Gray offended the moral sensibilities of British book reviewers, to the extent, in some cases, of saying that Wilde merited prosecution for violating the laws guarding public morality.

In the 30 June 1890 issue of the Daily Chronicle, the book critic said that Wilde’s novel contains “one element … which will taint every young mind that comes in contact with it.” In the 5 July 1890 issue of the Scots Observer, a reviewer asked “Why must Oscar Wilde ‘go grubbing in muck-heaps?'” The book critic of The Irish Times said, The Picture of Dorian Gray was “first published to some scandal.” Such book reviews achieved for the novel a “certain notoriety for being ‘mawkish and nauseous’, ‘unclean’, ‘effeminate’ and ‘contaminating’.” Such moralistic scandal arose from the novel’s homoeroticism, which offended the sensibilities (social, literary, and aesthetic) of Victorian book critics. Most of the criticism was, however, personal, attacking Wilde for being a hedonist with values that deviated from the conventionally accepted morality of Victorian Britain.

In response to such criticism, Wilde aggressively defended his novel and the sanctity of art in his correspondence with the British press. Wilde also obscured the homoeroticism of the story and expanded the personal background of the characters in the 1891 book edition.

Due to controversy, retailing chain WHSmith, then Britain’s largest bookseller, withdrew every copy of the July 1890 issue of Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine from its bookstalls in railway stations.

At Wilde’s 1895 trials, the book was called a “perverted novel” and passages (from the magazine version) were read during cross-examination. The book’s association with Wilde’s trials further hurt the book’s reputation. In the decade after Wilde’s death in 1900, the authorized edition of the novel was published by Charles Carrington, who specialized