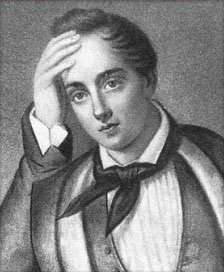

Yevgeny Abramovich Baratynsky (Russian: Евге́ний Абра́мович Бараты́нский; 2 March [O.S. 19 February] 1800 – 11 July 1844) was lauded by Alexander Pushkin as the finest Russian elegiac poet[citation needed]. After a long period when his reputation was on the wane, Baratynsky was rediscovered by Russian Symbolism poets as a supreme poet of thought

A member of the noble Baratynsky, or, more accurately, B(o)ratynsky family, the future poet received his education at the Page Corps at St. Petersburg, from which he was expelled at the age of 15 after stealing a snuffbox and five hundred roubles from the bureau of his accessory’s uncle. After three years in the countryside and deep emotional turmoil he entered the army as a private.

In 1820 the young poet met Anton Delvig, who rallied his failing spirits and introduced him to the literary press. Soon the military posted Baratynsky to Finland, where he remained for six years. His first long poem, Eda, written during this period, established his reputation.

In January 1826 he married the daughter of Major-General Gregory G. Engelhardt. Through the interest of friends he obtained leave from the Emperor to retire from the army, and he settled in 1827 in Muranovo just north of Moscow (now a literary museum). There he completed his longest work, The Gipsy, a poem written in the style of Pushkin.

Baratynsky’s family life seemed happy, but a profound melancholy remained in the background of his mind and of his poetry. He published several books of verse which Pushkin and other perceptive critics praised highly, but which met with a comparatively cool reception from the public, and with violent ridicule on the part of the young journalists of the “plebeian party”. As time went by, Baratynsky’s mood progressed from pessimism to hopelessness, and elegy became his preferred form of expression. He died in 1844 at Naples, where he had gone in pursuit of a milder climate.

Poetry

Baratynsky’s earliest poems are punctuated by conscious efforts to write differently from Pushkin whom he regarded as a model of perfection. Even Eda, his first long poem, though inspired by Pushkin’s The Prisoner of the Caucasus, adheres to a realistic and homely style, with a touch of sentimental pathos but not a trace of romanticism. It is written, like all that Baratynsky wrote, in a wonderfully precise style, next to which Pushkin’s seems hazy. The descriptive passages are among the best—the stern nature of Finland was particularly dear to Baratynsky.

His short pieces from the 1820s are distinguished by the cold, metallic brilliance and sonority of the verse. They are dryer and clearer than anything in the whole of Russian poetry before Akhmatova. The poems from that period include fugitive, light pieces in the Anacreontic and Horatian manner, some of which have been recognized as the masterpieces of the kind, as well as love elegies, where a delicate sentiment is clothed in brilliant wit.

In his mature work (which includes all his short poems written after 1829) Baratynsky is a poet of thought, perhaps of all the poets of the “stupid nineteenth century” the one who made the best use of thought as a material for poetry. This made him alien to his younger contemporaries and to all the later part of the century, which identified poetry with sentiment. His poetry is, as it were, a short cut from the wit of the 18th-century poets to the metaphysical ambitions of the twentieth (in terms of English poetry, from Alexander Pope to T. S. Eliot).

Baratynsky’s style is classical and dwells on the models of the previous century. Yet in his effort to give his thought the tersest and most concentrated statement, he sometimes becomes obscure by sheer dint of compression. Baratynsky’s obvious labour gives his verse a certain air of brittleness which is at poles’ ends from Pushkin’s divine, Mozartian lightness and elasticity. Among other things, Baratynsky was one of the first Russian poets who were, in verse, masters of the complicated sentence, expanded by subordinate clauses and parentheses.