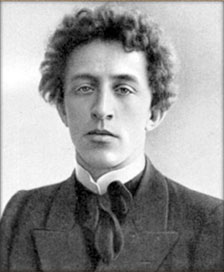

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok Born November 16 (28), 1880, St. Petersburg, Russian Empire Date of death August 7, 1921, Petrograd, RSFSR – Russian poet, classic of Russian literature of the 20th century, one of the greatest poets of Russia

Biography.

Mother – Alexandra Andreevna, née Beketova, (1860-1923) – daughter of the rector of St. Petersburg University A. N. Beketov. The marriage, which began when Alexandra was eighteen years old, turned out to be short-lived: after the birth of her son, she broke off relations with her husband and subsequently never resumed them. In 1889, she obtained a decree from the Synod on the dissolution of her marriage with her first husband and married guards officer F. F. Kublitsky-Piottukh, leaving her son the surname of her first husband.

Nine-year-old Alexander settled with his mother and stepfather in an apartment in the barracks of the Life Grenadier Regiment, located on the outskirts of St. Petersburg, on the banks of the Bolshaya Nevka. In 1889 he was sent to the Vvedensky gymnasium. In 1897, finding himself with his mother abroad, in the German resort town of Bad Nauheim, Blok experienced his first strong youthful love with Ksenia Sadovskaya. She left a deep mark on his work. In 1897, at a funeral in St. Petersburg, he met Vl. Soloviev.

In 1898 he graduated from high school and entered the law faculty of St. Petersburg University. Three years later he transferred to the Slavic-Russian department of the Faculty of History and Philology, which he graduated in 1906. At the university, Blok meets Sergei Gorodetsky and Alexei Remizov.

At this time, the poet’s second cousin, later the priest Sergei Mikhailovich Solovyov (junior), became one of the closest friends of the young Blok.

Blok wrote his first poems at the age of five. At the age of 10, Alexander Blok wrote two issues of the magazine “Ship”. From 1894 to 1897, he and his brothers wrote the handwritten journal “Vestnik”. Since childhood, Alexander Blok spent every summer on his grandfather’s Shakhmatovo estate near Moscow. 8 km away was the estate of Beketov’s friend, the great Russian chemist Dmitry Mendeleev Boblovo. At the age of 16, Blok became interested in theater. In St. Petersburg, Alexander Blok enrolled in a theater club. However, after his first success, he was no longer given roles in the theater.

In 1903, Blok married Lyubov Mendeleeva, daughter of D. I. Mendeleev, the heroine of his first book of poems, “Poems about a Beautiful Lady.” It is known that Alexander Blok had strong feelings for his wife, but periodically maintained connections with various women: at one time it was the actress Natalya Nikolaevna Volokhova, then the opera singer Lyubov Aleksandrovna Andreeva-Delmas. Lyubov Dmitrievna also allowed herself hobbies. On this basis, Blok had a conflict with Andrei Bely, described in the play “Balaganchik”. Bely, who considered Mendeleeva the embodiment of a Beautiful Lady, was passionately in love with her, but she did not reciprocate his feelings. However, after the First World War, relations in the Blok family improved, and in recent years the poet was the faithful husband of Lyubov Dmitrievna.

In 1909, two difficult events occur in the Blok family: Lyubov Dmitrievna’s child dies and Blok’s father dies. To come to his senses, Blok and his wife go on vacation to Italy and Germany. For his Italian poetry, Blok was accepted into a society called the “Academy.” In addition to him, it included Valery Bryusov, Mikhail Kuzmin, Vyacheslav Ivanov, Innokenty Annensky.

In the summer of 1911, Blok again traveled abroad, this time to France, Belgium and the Netherlands. Alexander Alexandrovich gives a negative assessment of French morals:

The inherent quality of the French (and the Bretons, it seems, predominantly) is inescapable dirt, first of all physical, and then mental. It is better not to describe the first dirt; to put it briefly, a person in any way squeamish will not agree to settle in France.

In the summer of 1913, Blok again went to France (on the advice of doctors) and again wrote about negative impressions:

Biarritz is overrun by the French petty bourgeoisie, so that even my eyes are tired of looking at ugly men and women… And in general, I must say that I am very tired of France and want to return to a cultural country – Russia, where there are fewer fleas, almost no French women, there is food (bread and beef), drink (tea and water); beds (not 15 arshins wide), washbasins (there are basins from which you can never empty all the water, all the dirt remains at the bottom)…

In 1912, Blok wrote the drama “Rose and Cross”. K. Stanislavsky and V. Nemirovich-Danchenko liked the play, but the drama was never staged in the theater.

On July 7, 1916, Blok was called up to serve in the engineering unit of the All-Russian Zemstvo Union. The poet served in Belarus. By his own admission in a letter to his mother, during the war his main interests were “food and horses.”

Revolutionary years.

Blok met the February and October revolutions with mixed feelings. He refused to emigrate, believing that he should be with Russia in difficult times. At the beginning of May 1917, he was hired by the “Extraordinary Commission of Inquiry to investigate illegal actions of former ministers, chief managers and other senior officials of both civil, military and naval departments” as an editor. In August, Blok began working on a manuscript, which he considered as part of the future report of the Extraordinary Investigative Commission and which was published in the magazine “Byloe” (No. 15, 1919) and in the form of a book called “The Last Days of Imperial Power” (Petrograd, 1921).

Blok immediately accepted the October Revolution enthusiastically, but as a spontaneous uprising, a rebellion.

At the beginning of 1920, Franz Feliksovich Kublitsky-Piottukh died from pneumonia. Blok took his mother to live with him. But she and Blok’s wife did not get along with each other.

In January 1921, on the occasion of the 84th anniversary of Pushkin’s death, Blok delivered his famous speech “On the Appointment of a Poet” at the House of Writers.

Illness and death.

Blok was one of those artists in Petrograd who not only accepted Soviet power, but agreed to work for its benefit. The authorities began to widely use the poet’s name for their own purposes.

During 1918-1920. Blok, often against his will, was appointed and elected to various positions in organizations, committees, and commissions. The constantly increasing volume of work undermined the poet’s strength. Fatigue began to accumulate – Blok described his state of that period with the words “I was drunk.” This may also explain the poet’s creative silence – he wrote in a private letter in January 1919: “For almost a year now I have not belonged to myself, I have forgotten how to write poetry and think about poetry…”. Heavy workloads in Soviet institutions and living in hungry and cold revolutionary Petrograd completely undermined the poet’s health – Blok developed serious cardiovascular disease, asthma, mental disorders, and scurvy began in the winter of 1920.

In the spring of 1921, Alexander Blok, together with Fyodor Sologub, asked to be issued exit visas. The issue was considered by the Politburo of the Central Committee of the RCP(b). Exit was denied. Lunacharsky noted: “We literally, without releasing the poet and without giving him the necessary satisfactory conditions, tortured him.” A number of historians believed that V.I. Lenin and V.R. Menzhinsky played a particularly negative role in the fate of the poet, prohibiting the patient from leaving for treatment in a sanatorium in Finland, which, at the request of Maxim Gorky and Lunacharsky, was discussed at a meeting of the Politburo of the Central Committee RCP(b) July 12, 1921. Procured by L.B.

Kamenev and A.V. Lunacharsky at the subsequent meeting of the Politburo, the permission to leave on July 23, 1921 was late and could no longer save the poet.

Finding himself in a difficult financial situation, he was seriously ill and died on August 7, 1921 in his last Petrograd apartment from inflammation of the heart valves. A few days before his death, a rumor spread throughout St. Petersburg that the poet had gone crazy. Indeed, on the eve of his death, Blok raved for a long time, obsessed with a single thought: had all the copies of “The Twelve” been destroyed? However, the poet died in full consciousness, which refutes rumors about his insanity. Before his death, after receiving a negative response to a request to go abroad for treatment (dated July 12), the poet deliberately destroyed his notes and refused to take food and medicine.

The poet was buried at the Smolensk Orthodox cemetery in Petrograd. The Beketov and Kachalov families are also buried there, including the poet’s grandmother Ariadna Alexandrovna, with whom he was in correspondence. The funeral service was performed by Archpriest Alexey Zapadlov on August 10 (July 28, Art. – the day of celebration of the Smolensk Icon of the Mother of God) in the Church of the Resurrection of Christ. In 1944, Blok’s ashes were reburied on the Literary Bridge at the Volkovskoye Cemetery.

Family and relatives.

The poet’s relatives live in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Tomsk, Riga, Rome, Paris and England. Until recent years, Alexander Blok’s second cousin, Ksenia Vladimirovna Beketova, lived in St. Petersburg. Among Blok’s relatives is the editor-in-chief of the magazine “Our Heritage” – Vladimir Enisherlov.

Creation.

He began to create in the spirit of symbolism (“Poems about a Beautiful Lady”, 1901-1902), the feeling of noise that he proclaimed in the drama “Balaganchik” (1906). Blok’s lyrics, similar in their “spontaneity” to music, were formed under the influence of romance. Through the deepening of social influence (the “City” cycle, 1904-1908), religious interest (the “Snow Mask” cycle, published by “Ory”, St. Petersburg 1907), understanding the “terrible world” (cycle of the same name 1908-1916), awareness the tragedy of modern man (the play “The Rose and the Cross,” 1912–1913) came to the idea of the inevitability of “retribution” (the cycle of the same name, 1907–1913; the “Yambi” cycle, 1907–1914; the poem “Retribution,” 1910–1921). The main themes of poetry were resolved in the cycle “Motherland” (1907-1916).

The paradoxical combination of the mystical and the everyday, the detached and the everyday is generally characteristic of Blok’s entire work as a whole. This is a special form and its mental organization, and, like philosophy, its own block symbolism. Particularly characteristic in this regard is the classic examination of the hazy silhouette of “The Stranger” and “drunkards with rabbit eyes,” which has become a textbook. In general, Blok was very sensitive to the everyday impressions and sounds that surrounded his city and artists, he encountered and sympathized with them.

Before the revolution, the musicality of Blok’s poems lulled the audience, plunging them into a kind of somnambulistic sleep. Then the intonations of desperate, soul-grabbing gypsy songs appeared in his works (after private visits to cafes and concerts of this genre).

At first, the Bloc accepted the February and October revolutions with readiness, full support and even enthusiasm, which, by the way, lasted a little more than one short and difficult year of 1918. As Yu. P. Annenkov noted,

in the 1917-18th evening, Blok was finally captured by the spontaneous side of the revolution. “World fire” seemed to him to be a Goal, not a stage. The world fire was not even a symbol of destruction for Blok: it was “the world orchestra of the people’s soul.” Street lynchings turned out to be more justifiable for him than legal proceedings.

– (Yu. P. Annenkov, “Memories of Blok”).

This position of Blok caused a sharp assessment of a number of other literary figures – in particular, I. A. Bunin:

Blok openly joined the Bolsheviks. I published an article that Kogan (P.S.) admires. <…> The song is generally simple, Blok is a stupid man. Russian literature is extraordinarily corrupted behind its sounds. The street and the crowd began to play a very important role. Everything – and especially literature – goes out into the street, is connected with it and falls under its influence. “There is a Jewish pogrom in Zhmerinka, just as there was a pogrom in Znamenka…” This is called, according to Blok, “the people are embracing the musical revolution – listen, listen to the musical revolution!”

– (I. A. Bunin, “Cursed Days”).

Blok tried to comprehend the October Revolution not only in journalism, but also, which is especially significant, in his entire previous work the poem “The Twelve” (1918) was not found. This striking and generally misunderstood work stands entirely apart from Russian literature of the Silver Age and has caused controversy (both on the left and on the right) throughout the 20th century. Strange as it may seem, the key to the first understanding of the poem can be found in the work of the popular in pre-revolutionary Petrograd, the current almost forgotten chansonnier and poet M. N. Savoyarov, on friendly terms with whom the bloc was in 1915-1920 with songs and concerts that auditioned ten times. Judging by the poetic language of the poem “The Twelve,” Blok has at least changed a lot, his post-revolutionary style has become almost unrecognizable. And, despite everything, he was influenced by the influential singer, poet and eccentric Mikhail Savoyarov. According to Viktor Shklovsky, the poem “The Twelve” was unanimously condemned and few people understood it precisely because it was too difficult for Blok to take everything seriously and only seriously:

“Twelve” is an ironic thing. She didn’t even write in a ditty style, she wrote in a “thieves’” style. The style of a street verse like Savoyard’s.

We find real confirmation of this thesis in Blok’s notebooks. In March 1918, when his wife Lyubov Dmitrievna prepared to read the poem “The Twelve” aloud at evenings and concerts, Blok specially took her to Savoyard concerts to show her how and with what intonation these poems should be read. In an everyday, eccentric, even shocking… but not at all “symbolist” and habitually “Blok” manner… This is how the poet painfully tried to distance himself from the nightmare that surrounded him in the last three years of Petrograd (and Russian) life…, either criminal, or military, or some strange intertemporal…

In February 1919, the Blok was recognized by the Petrograd Extraordinary Commission. He was also suspected of an anti-Soviet conspiracy. A day later, after two long interrogations, Blok was finally released, since Lunacharsky stood up for him. However, even this day and a half of waiting broke him. In 1920, Blok wrote in his diary:

…under the yoke of violence, human conscience becomes silent; then a person withdraws into the old; The more brazen the violence, the more firmly a person locks himself into the old. This is what happened with Europe under the yoke of war, and with Russia now.

For Blok, the rethinking of revolutionary events and the fate of Russia was accompanied by a deep creative crisis, depression and progressive illness. After the surge of January 1918, when “Scythians” and “Twelve” were created at once, Blok completely stopped writing poetry and answered all questions about his silence: “All sounds have stopped… Don’t you hear that there are no sounds?” And to the artist Annenkov, the author of cubist illustrations for the first edition of the poem “The Twelve,” he complained: “I’m suffocating, suffocating, suffocating! We are suffocating, we will all suffocate. The world revolution is turning into a world angina pectoris!

The last cry of despair was the speech Blok read in February 1921 at an evening dedicated to the memory of Pushkin. This speech was listened to by both Akhmatova and Gumilyov, who came to the reading in a tailcoat, arm in arm with a lady who was shivering from the cold in a black dress with a deep neckline (the hall, as always in those years, was unheated, steam was clearly coming from everyone’s mouths) . Blok stood on the stage in a black jacket over a white turtleneck sweater, with his hands in his pockets. Quoting Pushkin’s famous line: “There is no happiness in the world, but there is peace and will…” – Blok turned to the discouraged Soviet bureaucrat sitting right there on the stage (one of those who, according to the caustic definition of Andrei Bely, “don’t write anything, only sign”). and minted:

…peace and freedom are also taken away. Not external peace, but creative peace. Not childish will, not the freedom to be liberal, but creative will—secret freedom. And the poet dies because he can no longer breathe: life has lost its meaning for him.

Blok’s poetic works have been translated into many languages of the world.

Memory of Blok.

Poem by Alexander Blok on the wall of one of the houses in Leiden (Netherlands)

The museum-apartment of A. A. Blok in St. Petersburg is located on Dekabristov Street, 57.

State Historical, Literary and Natural Museum-Reserve of A. A. Blok in Shakhmatovo

Monument to Blok in Moscow, on Spiridonovka Street

His poem “Night, Street, Lantern, Pharmacy” was turned into a monument on one of the streets of Leiden. Blok became the third poet after Marina Tsvetaeva and William Shakespeare, whose poems were painted on the walls of houses in this city as part of the “Wall poems” cultural project.

Names given in honor of Blok

Lyceum No. 1 named after. A. Blok in the city of Solnechnogorsk.

On February 22, 1939, the former Zavodskaya Street in Leningrad, located not far from Blok’s last apartment, was renamed Alexander Blok Street.

Streets in Kyiv, Krasnogorsk, Rostov-on-Don, Ust-Abakan, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk and other settlements of the states of the former USSR were named in memory of Alexander Blok.

The asteroid (2540) Block is named after the poet.

In philately:

USSR stamp, 1956

USSR stamp dedicated to Blok, 1980 (TsFA 5128, Scott 4880)

In art:

For the centenary of the poet, a television film “And the Eternal Battle… From the Life of Alexander Blok” was shot in the USSR (Alexander Ivanov-Sukharevsky starred as Blok). The image of Blok also appears in the films Doctor Zhivago, 2002 (played by David Fisher), Garpastum, 2005 (Gosha Kutsenko), Yesenin, 2005 (Andrei Rudensky).

Places associated with the Block:

Addresses in St. Petersburg – Petrograd

“Rector’s wing” of St. Petersburg University, where A. Blok was born and lived

November 16, 1880-1883 – “rector’s wing” of the St. Petersburg Imperial University – Universitetskaya embankment, 9 (in 1974, in memory of the birth of A. A. Blok, a marble memorial plaque was unveiled here, architect T. N. Miloradovich);

1883-1885 – apartment building – Panteleimonovskaya street, 4;

1885-1886 – apartment building – Ivanovskaya (now Socialist) street, 18;

1886-1889 – apartment building – Bolshaya Moskovskaya Street, 9;

Cenotaph of A. A. Blok at the Smolensk cemetery in St. Petersburg

1889-1906 – apartment of F. F. Kublitsky-Piottukh in the officer barracks of the Life Guards Grenadier Regiment – Petersburg (now Petrogradskaya) embankment, 44 (a granite memorial plaque was installed in 1980, architect T. N. Miloradovich);

1902-1903 – furnished room on Serpukhovskaya Street, 10, where Blok and Mendeleeva lived before their wedding. A year later, the room had to be abandoned, as the police demanded Blok’s passport for registration.

September 1906 – autumn 1907 – apartment building – Lakhtinskaya street, 3, apt. 44;

autumn 1907-1910 – courtyard wing of the mansion of A. I. Thomsen-Bonnara – Galernaya Street, 41;

1910-1912 – apartment building – Bolshaya Monetnaya Street, 21/9, apt. 27;

1912-1920 – apartment building of M. E. Petrovsky – Ofitserskaya Street (since 1918 – Dekabristov Street), 57, apt. 21;

1914 – Tenishev School in St. Petersburg. In April 1914, here, staged by V. E. Meyerhold, the premiere of the lyrical drama “The Stranger” and the third edition of Meyerhold’s interpretation of Blok’s “Balaganchik” took place, at which the poet was present.

08/06/1920 – 08/07/1921 – apartment building of M.E. Petrovsky – Dekabristov Street, 57, apt. 23 (there is a memorial plaque installed in 1946).

In August 1916, the poet visited Belarus, when the “war with the Germans” was rolling across its territory. The poet’s Polesie roads – from Parakhonsk to Luninets, then to the village of Kolby, Pinsk region. On the way to the Pinsk region, he stopped in Mogilev and Gomel, visiting the sights, especially the Rumyantsev-Paskevich Palace.

Entry in the poet’s diary: “Theme for a fantastic story: “Three hours in Mogilev on the Dnieper.” High bank, white churches above the moon and fast twilight.” Apparently, Blok wrote a story about Mogilev, but did not have time to publish it. Along with other manuscripts, it was destroyed in the Shakhmatovo estate during a fire in 1921