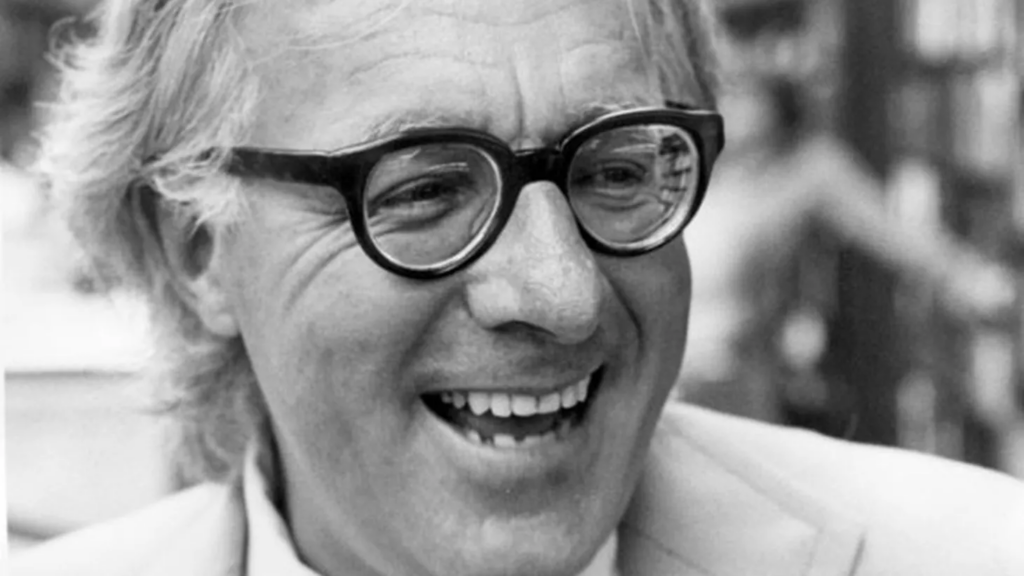

A Pleasure to Burn, Ray Bradbury

Contents

The Reincarnate

Pillar of Fire

The Library

Bright Phoenix

The Mad Wizards of Mars

Carnival of Madness

Bonfire

The Cricket on the Hearth

The Pedestrian

The Garbage Collector

The Smile

Long After Midnight

The Fireman

Bonus Stories

The Dragon Who Ate His Tail

Sometime Before Dawn

To the Future

The Reincarnate

After a while you will get over the inferiority complex. Maybe. There’s nothing you can do about it. Just be careful to walk around at night. The hot sun is certainly difficult on you. And summer nights aren’t particularly helpful. So the best thing for you to do is wait for chilly weather. The first six months are your prime. The seventh month the water will seep through and the maggots will begin. By the end of the eighth month your usefulness will dwindle. By the tenth month you’ll lie exhausted and weeping the sorrow without tears, and you will know then that you will never move again.

But before that happens there is so much to be thought about, and finished. Many thoughts to be renewed, many old likes and dislikes to be turned in your mind before the sides of your skull fall away.

It is new to you. You are born again. And your womb is silk-lined and fine-smelling of tuberoses and linens, and there is no sound before your birth except the beating of the Earth’s billion insect hearts. Your womb is wood and metal and satin, offering no sustenance, but only an implacable slot of close air, a pocket within the mother soil. And there is only one way you can live, now.

There must be an emotional hand to slap you on the back to make you move. A desire, a want, an emotion. Then the first thing you know you quiver and rise and strike your brow against silk-skinned wood. That emotion surges through you, calling you. If it is not strong enough, you will settle down wearily, and will not wake again. But if you grow with it, somehow, if you claw upward, if you work tediously, slowly, many days, you find ways of displacing earth an inch at a time, and one night you crumble the darkness, the exit is completed, and you wriggle forth to see the stars.

Now you stand, letting the emotion lead you as a slender antenna shivers, led by radio waves. You bring your shoulders to a line, you make a step, like a new born babe, stagger, clutch for support—and find a marble slab to lean against. Beneath your trembling fingers the carved brief story of your life is all too tersely told: Born—Died.

You are a stick of wood. Learning to unbend, to walk naturally again, is not easy. But you don’t worry about it. The pull of this emotion is too strong in you, and you go on, outward from the land of monuments, into twilight streets, alone on the pale sidewalks, past brick walls, down stony paths.

You feel there is something left undone. Some flower yet unseen somewhere where you would like to see, some pool waiting for you to dive into, some fish uncaught, some lip unkissed, some star unnoticed. You are going back, somewhere, to finish whatever there is undone.

All the streets have grown strange. You walk in a town you have never seen, a sort of dream town on the rim of a lake. You become more certain of your walking now, and can go quite swiftly. Memory returns.

You know every cobble of this street, you know every place where asphalt bubbled from mouths of cement in the hot oven summer. You know where the horses were tethered sweating in the green spring at these iron posts so long ago it is a feeble maggot in your brain. This cross street, where a light hangs high like a bright spider spinning a light web across this one solitudinous spot. You soon escape its web, going on to sycamore gloom. A picket fence dances woodenly beneath probing fingers. Here, as a child, you rushed by with a stick in hand manufacturing a machine-gun racket, laughing.

These houses, with the people and memories of people in them. The lemon odor of old Mrs. Hanlon who lived there, remember? A withered lady with withered hands and gums withered when her teeth gleamed upon the cupboard shelf smiling all to their porcelain selves. She gave you a withered lecture every day about cutting across her petunias. Now she is completely withered like a page of ancient paper burned. Remember how a book looks burning? That’s how she is in her grave now, curling, layer upon layer, twisting into black rotted and mute agony.

The street is quiet except for the walking of a man’s feet on it. The man turns a corner and you unexpectedly collide with one another.

You both stand back. For a moment, examining one another, you understand something about one another.

The stranger’s eyes are deep-seated fires in worn receptacles. He is a tall, slender man in a very neat dark suit, blond and with a fiery whiteness to his protruding cheekbones. After a moment, he bows slightly, smiling. “You’re a new one,” he says. “Never saw you before.”

And you know then what he is. He is dead, too. He is walking, too. He is “different” just like yourself.

You sense his differentness.

“Where are you going in such a hurry?” he asks, politely.

“I have no time to talk,” you say, your throat dry and shrunken. “I am going somewhere, that is all. Please, step aside.”

He holds onto your elbow firmly. “Do you know what I am?” He bends closer. “Do you not realize we are of the same legion? The dead who walk. We are as brothers.”

You fidget impatiently. “I—I have no time.”

“No,” he agrees, “and neither have I, to waste.”

You brush past, but cannot lose him, for he walks with you. “I know where you’re going.”

“Do you?”

“Yes,” he says, casually. “To some childhood haunt. To some river. To some house or some memory. To some woman, perhaps. To some old friend’s cottage. Oh, I know, all right, I know everything about our kind. I know,” he says, nodding in the passing light and dark.

“You know, do you?”

“That is always why the dead walk. I have discovered that. Strange, when you think of all the books ever written about the dead, about vampires and walking cadavers and such, and never once did the authors of those most worthy volumes hit upon the true secret of why the dead walk. Always it is for the same reason—a memory, a friend, a woman, a river, a piece of pie, a house, a drink of wine, everything and anything connected with life and—LIVING!” He made a fist to hold the words tight. “Living! REAL living!”

Wordless, you increase your stride, but his whisper paces you:

“You must join me later this evening, my friend. We will meet with the others, tonight, tomorrow night and all the nights until we have our victory.”

Hastily. “Who are the others?”

“The other dead.” He speaks grimly. “We are banding together against intolerance.”

“Intolerance?”

“We are a minority. We newly dead and newly embalmed and newly interred, we are a minority in the world, a persecuted minority. We are legislated against. We have no rights!” he declares heatedly.

The concrete slows under your heels. “Minority?”

“Yes.” He takes your arm confidentially, grasping it tighter with each new declaration. “Are we wanted? No! Are we liked? No! We are feared! We are driven like sheep into a marble quarry, screamed at, stoned and persecuted like the Jews of Germany! People hate us from their fear. It’s wrong, I tell you, and it’s unfair!” He groans. He lifts his hands in a fury and strikes down.

You are standing still now, held by his suffering and he flings it at you, bodily, with impact. “Fair, fair, is it fair? No. I ask you. Fair that we, a minority, rot in our graves while the rest of the continent sings, laughs, dances, plays, rotates and whirls and gets drunk! Fair, is it fair, I ask you that they love while our lips shrivel cold, that they caress while our fingers manifest to stone, that they tickle one another while maggots entertain us!

“No! I shout it! It is ungodly unfair! I say down with them, down with them for torturing our minority! We deserve the same rights!” he cries. “Why should we be dead, why not the others?”

“Perhaps you are right.”

“They throw us down and slam the earth in our white faces and load a carven stone over our bosom to weigh us with, and shove flowers into an old tin can and bury it in a small spaded hole once a year. Once a year? Sometimes not even that! Oh, how I hate them, oh how it rises in me, this full blossoming hatred for the living. The fools. The damn fools! Dancing all night and loving, while we lie recumbent and full of disintegrating and helpless passion! Is that right?”

“I hadn’t thought about it,” you say, vaguely.

“Well,” he snorts, “well, we’ll fix them.”

“What will you do?”

“There are thousands of us gathering tonight in the Elysian Park and I am the leader! We will destroy humanity!” he shouts, throwing back his shoulders, lifting his head in rigid defiance. “They have neglected us too long, and we shall kill them. It’s only right. If we can’t live, then they have no rights to live, either! And you will come, won’t you, my friend?” he says, hopefully. “I have coerced many, I have spoken with scores. You will come and help. You yourself are bitter with this embalming and this suppression, are you not,