Pieta Summer, Ray Bradbury

Pietà Summer

‘Gosh, I can hardly wait!’ I said.

‘Why don’t you shut up?’ my brother replied.

‘I can’t sleep,’ I said. ‘I can’t believe what’s happening tomorrow. Two circuses in just one day! Ringling Brothers coming in on that big train at five in the morning, and Downey Brothers coming by truck a couple hours later. I can’t stand it.’

‘Tell you what,’ my brother said. ‘Go to sleep. We gotta get up at four-thirty.’

I rolled over but I just couldn’t sleep because I could hear those circuses coming over the edge of the world, rising with the sun.

Before we knew it, it was 4:30 A.M. and my brother and I were up in the cold darkness, getting dressed, grabbing an apple for breakfast, and then running out in the street and heading down the hill toward the train yards.

As the sun began to rise the big Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey train of ninety-nine cars loaded with elephants, zebras, horses, lions, tigers, and acrobats arrived; the huge engines steaming in the dawn, puffing out great clouds of black smoke, and the freight cars sliding open to let the horses hoof out into the darkness, and the elephants stepping down, very carefully, and the zebras, in huge striped flocks, gathering in the dawn, and my brother and I standing there, shivering, waiting for the parade to start, for therewasgoing to be a parade of all the animals up through the dark morning town toward the distant acres where the tents would whisper upward toward the stars.

Sure enough my brother and I walked with the parade up the hill and through the town that didn’t know we were there. But there we were, walking with ninety-nine elephants and one hundred zebras and two hundred horses, and the big bandwagon, soundless, out to the meadow that was nothing at all, but suddenly began to flower with the big tents sliding up.

Our excitement increased by the minute because where just hours ago there had been nothing at all, now there was everything in the world.

By seven-thirty Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey had pretty well got its tents up and it was time for me and my brother to race back to where the motorcars were unloading the tiny Downey Brothers circus; a miniature version of the large miracle, it poured out of trucks instead of trains, with only ten elephants instead of nearly one hundred, and just a few zebras, and the lions, drowsing in their separate cages, looked old and mangy and exhausted. That applied to the tigers, too, and the camels that looked as if they’d been walking a hundred years, their pelts beginning to drop off.

My brother and I worked through the morning carrying cases of Coca-Cola, in real glass bottles, instead of plastic, so that lugging one of those cases meant carrying fifty pounds. By nine o’clock in the morning I was exhausted because I had had to move forty or more cases, taking care to avoid being trampled by one of the monster elephants.

At noon we raced home for a sandwich and then back to the small circus for two hours of explosions, acrobats, trapeze performers, mangy lions, clowns, and Wild West horse riding.

With the first circus done, we raced home and tried to rest, had another sandwich, then walked back to the big circus with our father at eight o’clock.

Another two hours of brass thunder followed, avalanches of sound and racing horses, expert marksmen, and a cage full of truly irritable and brand-new dangerous lions. At some point my brother ran off, laughing, with some friends, but I stayed fast by my father’s side.

By ten o’clock the avalanches and explosions came to a stunned halt. The parade I had witnessed at dawn was now reversed, and the tents were sighing down to lie like great pelts on the grass.

We stood at the edge of the circus as it exhaled, collapsed its tents, and began to move away in the night, the darkness filled with a procession of elephants huffing their way back to the train yard. My father and I stood there, quiet, watching.

I put my right foot forward to start the long walk home when, suddenly, a strange thing happened: I went to sleep on my feet. I didn’t collapse, I felt no terror, but quite suddenly I simply could not move.

My eyes clamped shut and I began to fall, when suddenly I felt strong arms catch me and I was lifted into the air. I could smell the warm nicotine breath of my father as he cradled me in his arms, turned, and began the long shuffling walk home.

Incredible, the whole thing, for we were more than a mile from our house and it was truly late and the circus had almost vanished and all its strange people were gone.

On that empty sidewalk my father marched, cradling me in his arms for that great distance, impossible, for after all I was a thirteen-year-old boy weighing ninety-two pounds.

I could feel his difficult gasps as he gripped me, yet I could not fully wake. I struggled to blink my eyes and move my arms, but soon I was fast asleep and for the next half hour I had no way of knowing that I was being toted, a strange burden, through a town that was dousing its lights.

From far off I vaguely heard voices and someone saying, ‘Come sit down, rest for a moment.’

I struggled to listen and felt my father jolt and sit. I sensed that somewhere on the homeward journey we had passed a friend’s house and that the voice had called to my father to come rest on the porch.

We were there for five minutes, maybe more, my father holding me on his lap and me, still half asleep, listening to the gentle laughter of my father’s friend, commenting on our strange odyssey.

At last the gentle laughter subsided. My father sighed, rose, and my half slumber continued. Half in and half out of dreams, I felt myself carried the final mile home.

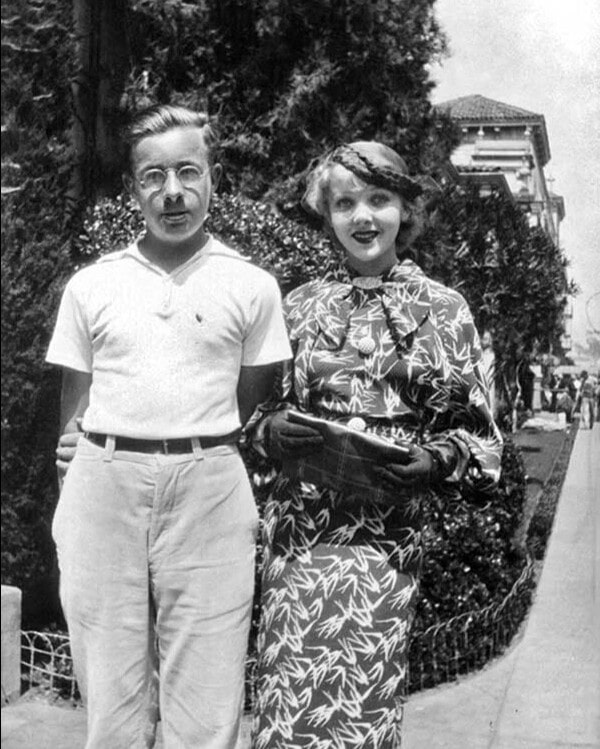

The image I still have, seventy years later, is of my fine father, not for a moment making anything but a wry comment, carrying me through the night streets; probably the most beautiful memory a son ever had of someone who cared for him and loved him and didn’t mind the long walk home through the night.

I’ve often referred to it, somewhat fancifully, as our pietà, the love of a father for his son–the walk on that long sidewalk, surrounded by those unlit houses as the last of the elephants vanished down the main avenue toward the train yards, where a locomotive whistled and the train steamed, getting ready to rush off into the night, carrying a tumult of sound and light that would live in my memory forever.

The next day I slept through breakfast, slept through the morning, slept through lunch, slept all afternoon, and finally wakened at five o’clock and staggered in to sit at dinner with my brother and my folks.

My father sat quietly, cutting his steak, and I sat across from him, examining my food.

‘Papa,’ I suddenly cried, tears falling from my eyes. ‘Oh, thank you, Papa, thank you!’

My father cut another piece of steak and looked at me, his eyes shining very brightly.

‘For what?’ he said.

The end