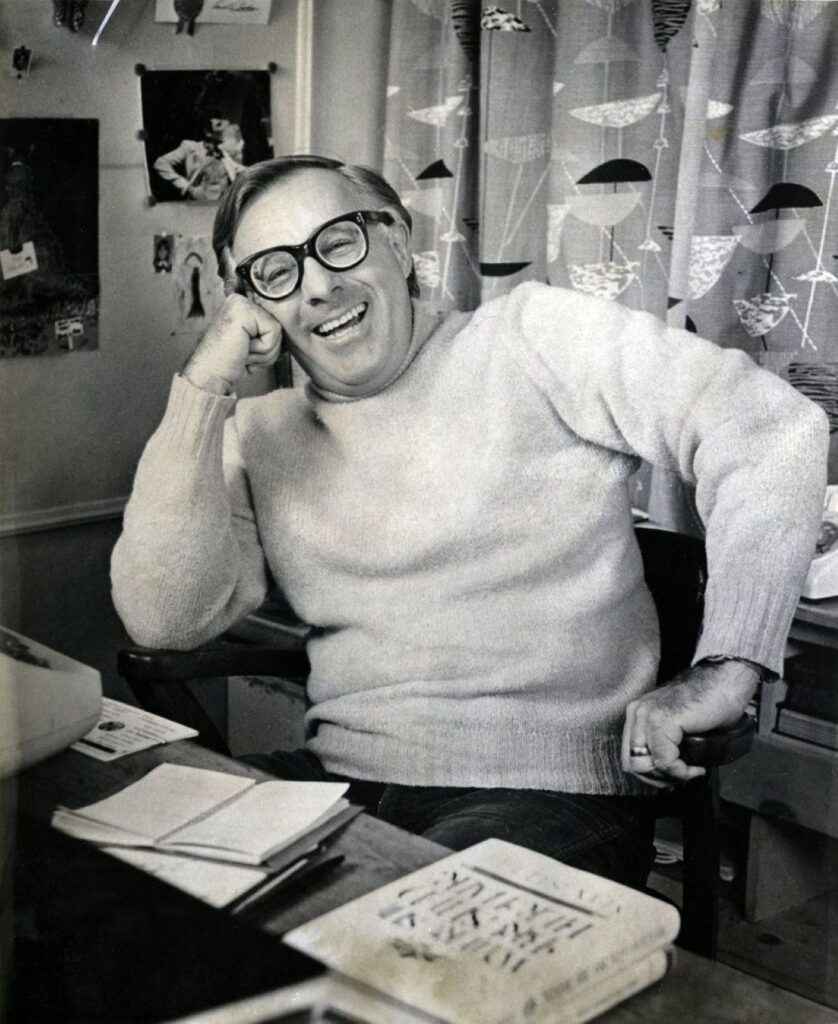

Tangerine, Ray Bradbury

Tangerine

One night about a year ago I was having a late dinner, alone, in a fine restaurant, feeling good about myself and my place in the world (a nice feeling to have when you’re in your seventies), when, sipping my second glass of wine, I glanced at my waiter, whose presence until now had been over my shoulder or at a distance.

It was like those moments in a movie when the film jerks in the projector and freezes a single image. I felt my breath catch.

I knew this waiter from another year. And knew that I hadn’t seen him for a lifetime. My age, yet he was recognizable, so when he came forward to pour the rest of my wine I dared to speak.

“I think I know you,” I said.

The waiter glanced at me and said, “No, I don’t think—”

But, closer now, the same forehead, same cut of hair, ears, the chin, same weight as half a century back, so his face hadn’t changed.

“Fifty-seven years ago,” I said. “Before the war.”

The waiter’s eyes slid to the side, then back. “No, I don’t believe—”

“1939,” I said. “I was nineteen. You must’ve been the same.”

“1939?” The waiter’s gaze checked my eyebrows, ears, nose, and finally my mouth. “You don’t look familiar.”

“Well,” I said. “My hair was light then, and I weighed forty pounds less, and I had no money for clothes, and I used to go downtown on Saturday nights to listen to the soap-box orators in the park. There was always a good fight.”

“Pershing Square.” The waiter nodded and half-smiled. “Yeah, yes. Sure. I went there once in a while. Summer of ’39. Pershing Square.”

“Most of us were just wandering young men, kids, lonely.”

“Nineteen’s lonely. You’ll do anything, even listen to a lot of hot air.”

“There was plenty of that.” I saw I had him hooked. “There used to be a little gang, not really a gang, like today, but five or six guys got to know each other, we had no money, so we kind of wandered around town, sometimes dropped into a beer parlor.

They’d ask you for your ID so all you could get was Cokes. Twenty-five cents I think it was for a Coke you could nurse for an hour and watch the crowd at the bar and the tables.”

“Petrelli’s.” The waiter touched his mouth as if the words were a surprise. “I haven’t thought of that place in years. But I don’t remember being there with you,” he said nervously. “What’s your name?”

“You never knew. We just called each other ‘hey’ or ‘you.’ We might have made up some names. Carl or Doug or Junior. You could’ve been Ramón.”

The waiter rolled his towel into a ball. “How did you know that? You must’ve heard—”

“No, it just came to me. Ramón, right?”

“Keep your voice down.”

“Ramón?” I said quietly.

He nodded abruptly. “Well, it’s been nice—”

He might have gone but I said, “We prowled around town, five or six of us, and one night one of the gang treated us to French Dip sandwiches down near City Hall. The young man who did it sang everywhere we went, sang and laughed, laughed and sang. What was his name?”

“Sonny,” the waiter said suddenly. “Sonny. And there was a song he sang a dozen times a night that summer.”

“‘Tangerine,’” I said.

“Ohmigod, what a memory!”

“Tangerine.”

Johnny Mercer wrote it. Sonny sang it.

Leading us through the night, a small crowd of six or seven.

“Tangerine.”

Sometimes we called him Tangerine, for that was his favorite song the summer of that year before everyone went away to war. Tangerine was it. We never found out what his last name was nor where he lived now or where he came from.

He was Friday nights late and Saturdays later, singing as he got off the streetcar like a great lady with refined manners and a look that said the world should have more flowers, but sadly did not.

Tangerine. Sonny. No name. He was tall for that year, just this side of six feet, with more skeleton and less flesh than the rest of us. He claimed that he was not thin but svelte and when he alighted in our midst one warm summer night the weather changed because he bade it to do so with a wave of a languid arm and pale fingers in which he held a long cigarette holder that he pointed at buildings, skylines, the park, or us, as he talked, or laughed.

There was nothing he didn’t laugh at, and after a while, fearing you might miss out, you joined his laughter. Life was pretty damned funny and you had best find that out now, rather than later.

Tangerine. Sonny. He drifted like a countess from a suddenly royal streetcar, swept through the park, gathering as he went all the lonelies, who, pulled by his gravity and grace, their eyes never off him, rarely speaking, followed.

It was as if they had been waiting all summer for something, anything, to happen. For someone to tell them where and who they were, and where to go. Taking it for granted, Sonny poised in the center of the red-bricked plaza, glanced about with disdain, and stabbed his cigarette holder toward those men shouting the virtues of Stalin or Hitler, choose one, choose none.

When Sonny arrived at the sound and fury, there were half a dozen aliens, wanderers in his wake. He did not glance back but accepted them, like a cape to be worn at this strange opera. He stood, eyes shut, listening to the shouts. His new friends did likewise, shut their eyes to accept the noise.

I was one of them.

And all of us nameless. Oh sure, there were Pete and Tom and Jim. But the giveaway was a young punk who claimed to be H. Bedford Jones. I knew he lied. I had read H. Bedford Jones’s novels in Argosy when I was ten.

But who needed names when Sonny dubbed and redubbed us weekends? This one was “Squirt” and that one “Tad,” and yet another “Elder Statesman,” and someone—me—was from another world, or he led our late-night parades, calling out “cohorts” or “chums” or just “pals” and “lonely hearts.”

I never found out much about those friends who were really not friends but late-night tourists from various cities. In later years I described L.A. and its eighty or ninety towns as eighty-five oranges in search of a navel.

But in late 1939 there were only two places to socialize: Pershing Square, where the temperature rose from political explosions, or Hollywood, where people walked up and down in search of liaisons like ectoplasm that melted long before taking shape.

So it was with L.A. before the Second World War, when young men minus cars wandered in dead certain that by nine some fabulous woman would grab and hustle them home to deliriums.

It never happened. Which did not stop the young men the next weekend from shouting “Tonight’s the night” at their mirrors, knowing that when they turned away their glass images died. Thus a conglomerate gang gathered by instinct rather than intellect.

And there was Sonny.

His mirror was probably just as accurate as ours at showing defeat with nicely knotted ties and clean collars. But then mirrors are Rorschach tests; you can read anything in them that enhances your myopia or threatens your self-belief. Leaving on Saturday, you always checked the mirror to see if you were really there.

That being so, most Saturday nights were long and Sonny peacocked us around, buying hot dogs or Coca-Colas in bars full of strange men or stranger women. The men seemed to have broken wrists. The women had biceps. We nursed our Cokes for hours, stunned by the scene, until the managers threw us out.

“Okay,” cried Sonny in the doorway, “if that’s how you feel!”

“That’s how I feel!” the managers replied.

“Come on, girls,” said Sonny.

“I wish you wouldn’t say that,” I said.

“Sorry.” Sonny left. “This way, chaps.”

Some Saturday nights ended early. Sonny disappeared. And without Sonny the gang disintegrated. We didn’t know what to talk about without him. We never knew where Sonny went but once we thought we saw him duck into a cheap hotel on Main Street with an old white-haired gentleman, but when we got there the lobby was empty.

Another time we saw him on a bus that cost ten cents rather than a trolley that cost seven, standing by a tall slender colored boy. Then the trolley was gone. That did it. We said so long and rode home to addresses we never gave.

One Saturday night it rained without stopping and since most of the guys didn’t have enough money to hide in the bars, they went home, which left Sonny and me staring at each other, until he said:

“Okay, Peter Pan, you ever had a real drink? Booze, hooch, scotch, wine.”

“Nope.”

“C’mon, it’s time.”

He dragged me into the nearest bar and ordered a Coke and a double Dubonnet. When it came, he slid it over. “Try this.”

I sipped it and smiled. “Hey, not bad.”

“Not bad, he says!”

“Reminds me of the grapes when I was nine that me and my dad crushed in a wine press with lots of sugar. Dubonnet.”

“God! The child genius describes his first drink. When will you stop being Joan of Arc making the rounds?”

“No, no,” I said. “I’m the blacksmith who made her armor.”

“Give me that!” Sonny slugged the Dubonnet down. “Joan of Arc’s blacksmith! Christ! Out!” Sonny paid and we were on the street, where he stopped and teetered on the curb, staring.

I looked to where he was looking. She was there.

A woman of, I would say,