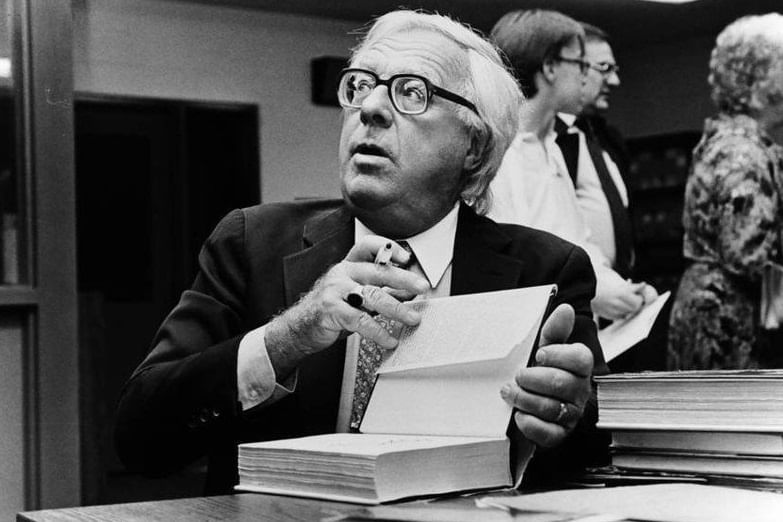

To The Chicago Abyss, Ray Bradbury

To The Chicago Abyss, Ray Bradbury (1963)

Under a pale April sky in a faint wind that blew out of memory of winter, the old man shuffled into the almost empty park at noon. His slow feet were bandaged with nicotine-stained swathes, his hair was wild, long and gray as was his beard which enclosed a mouth which seemed always atremble with revelation.

Now he gazed back as if he had lost so many things he could not begin to guess there in the tumbled ruin, the toothless skyline of the city.

Finding nothing, he shuffled on until he found a bench where sat a woman alone. Examining her, he nodded and sat to the far end of the bench and did not look at her again.

He remained, eyes shut, mouth working, for three minutes, head moving as if his nose were printing a single word on the air. Once it was written, he opened his mouth to pronounce it in a clear, fine voice: “Coffee.”

The woman gasped and stiffened. The old man’s gnarled fingers tumbled in pantomime on his unseen lap. “Twist the key! Bright-red, yellow-letter can! Compressed air. Hisss! Vacuum pack. Ssst! Like a snake!” The woman snapped her head about as if slapped, to stare in dreadful fascination at the old man’s moving tongue. “The scent, the odor, the smell. Rich, dark, wondrous Brazilian beans, fresh-ground!”

The woman tottered, sprung up, reeling as if gun-shot. The old man flicked his eyes wide. “No!” But she was running, gone. The old man sighed and walked on through the park until he reached a bench where sat a young man completely involved with wrapping dried grass in a small square of thin paper.

His thin fingers shaped the grass tenderly, in an almost holy ritual, trembling as he rolled the tube, put it to his mouth and, hypnotically, lit it. He leaned back, squinting deliciously, communing with the strange rank air in his mouth and lungs.

The old man watched the smoke blow away on the wind and said, “Chesterfields.”

The young man gripped his knees tight.

“Raleighs,” said the old man. “Lucky Strikes.” The young man stared at him. “Kent. Kool. Marlboro,” said the old man, not looking at him. “Those were the names. White, red, amber packs, grass green, sky blue, pure gold, with the red slick small ribbon that ran around the top that you pulled to zip away the crinkly cellophane, and the blue government tax stamp—“

“Shut up,” said the young man.

“Buy them in drugstores, fountains, subways–“

“Shut up!”

“Gently,” said the old man . “It’s just, that smoke of yours made me think-“

“Don’t think!” The young man jerked so violently his homemade cigarette fell in chaff to his lap . “Now look what you made me do!”

“I’m sorry. It was such a nice friendly day.”

“I’m no friend!”

“We’re all friends now, or why live?”

“Friends!” the young man snorted, aimlessly plucking at the shredded grass and paper.

“Maybe there were friends back in 1970, but now… “

“1970. You must have been a baby then . They still had Butterfingers then in bright-yellow wrappers . Baby Ruths . Clark Bars in orange paper. Milky Ways—swallow a universe of stars, comets, meteors. Nice.”

“It was never nice.” The young man stood suddenly. “What’s wrong with you?”

“I remember limes, and lemons, that’s what’s wrong with me. Do you remember oranges?”

“Damn right. Oranges, hell. You calling me a liar? You want me to feel bad? You nuts? Don’t you know the law? You know I could turn you in, you?”

“I know, I know,” said the old man, shrugging . “The weather fooled me. It made me want to compare-“

“Compare rumors, that’s what they’d say, the police, the special cops, they’d say it, rumors, you trouble making bastard, you.”

He seized the old man’s lapels, which ripped so he had to grab another handful, yelling down into his face . “Why don’t I just blast the living Jesus out of you? I ain’t hurt no-one in so long, I…”

He shoved the old man. Which gave him the idea to pummel, and when he pummeled he began to punch, and punching made it easy to strike, and soon he rained blows upon the old man, who stood like one caught in thunder and down-poured storm, using only his fingers to ward off blows that fleshed his cheeks, shoulders, his brow, his chin, as the young man shrieked cigarettes, moaned candies, yelled smokes, cried sweets until the old man fell to be kick-rolled and shivering.

The young man stopped and began to cry. At the sound, the old man, cuddled, clenched into his pain, took his fingers away from his broken mouth and opened his eyes to gaze with astonishment at his assailant.

The young man wept. “Please…” begged the old man.

The young man wept louder, tears falling from his eyes.

“Don’t cry,” said the old man. “We won’t be hungry forever. We’ll rebuild the cities. Listen, I didn’t mean for you to cry, only to think, where are we going, what are we doing, what’ve we done? You weren’t hitting me. You meant to hit something else, but I was handy. Look, I’m sitting up. I’m okay.”

The young man stopped crying and blinked down at the old man, who forced a bloody smile. “You… you can’t go around,” said the young man, “making people unhappy. I’ll find someone to fix you!”

“Wait!” The old man struggled to his knees. “No!”

But the young man ran wildly off out of the park, yelling. Crouched alone, the old man felt his bones, found one of his teeth lying red amongst the strewn gravel, handled it sadly. “Fool,” said a voice.

The old man glanced over and up. A lean man of some forty years stood leaning against a tree nearby, a look of pale weariness and curiosity on his long face. “Fool,” he said again.

The old man gasped. “You were there, all the time, and did nothing?”

“What, fight one fool to save another? No.” The stranger helped him up and brushed him off. “I do my fighting where it pays. Come on. You’re going home with me.”

The old man gasped again. “Why?”

“That boy’ll be back with the police any second. I don’t want you stolen away, you’re a very precious commodity. I’ve heard of you, looked for you for days now. Good grief, and when I find you you’re up to your famous tricks. What did you say to the boy made him mad?”

“I said about oranges and lemons, candy, cigarettes. I was just getting ready to recollect in detail wind-up toys, briar pipes and back scratchers, when he dropped the sky on me.”

“I almost don’t blame him. Half of me wants to hit you itself. Come on, double time. There’s a siren, quickly.” And they went swiftly, another way, out of the park.

He drank the homemade wine because it was easiest. The food must wait until his hunger overcame the pain in his broken mouth. He sipped, nodding. “Good, many thanks, good.”

The stranger who had walked him swiftly out of the park sat across from him at the flimsy dining-room table as the stranger’s wife placed broken and mended plates on the worn cloth.

“The beating,” said the husband at last. “How did it happen?”

At this the wife almost dropped a plate.

“Relax,” said the husband. “No one followed us. Go ahead, old man, tell us, why do you behave like a saint panting after martyrdom? You’re famous, you know. Everyone’s heard about you. Many would like to meet you. Myself, first, I want to know what makes you tick. Well?”

But the old man was only entranced with the vegetables on the chipped plate before him.

Twenty-six, no, twenty-eight peas! He counted the impossible sum! He bent to the incredible vegetables like a man praying over his quietest beads.

Twenty-eight glorious green peas, plus a few graphs of half-raw spaghetti announcing that today business was fair. But under the line of pasta, the cracked line of the plate showed where business for years now was more than terrible.

The old man hovered counting above the food like a great and inexplicable buzzard crazily fallen and roosting in this cold apartment, watched by his Samaritan hosts until at last he told, “These twenty-eight peas remind me of a movie I saw as a child. A comedian-do you know the word?-a funny man met a lunatic in a midnight house in this film and… “

The husband and wife laughed quietly. “No, that’s not the joke yet, sorry,” the old man apologized. “The lunatic sat the comedian down to an empty table, no knives, no forks, no food. “Dinner is served!” he cried.

Afraid of murder, the comedian fell in with the make-believe. ‘Great!’ he cried, pretending to chew steak, vegetables, dessert. He bit Nothing. ‘Finely’ he swallowed air. ‘Wonderful!” Erm… you may laugh now.”

But the husband and wife, grown still, only looked at their sparsely strewn plates.

The old man shook his head and went on. “The comedian, thinking to impress the madman, exclaimed, “And these spiced brandy Peaches are superb!” “Peaches!” screamed the madman, drawing a gun. “I served no peaches! You must be insane!” And shot the comedian in the behind!”

The old man, in the silence which ensued, picked up the first pea and weighed its lovely bulk upon his bent tin fork. He was about to put it in his mouth when there was a sharp rap on the door. “Special police!” a voice cried.

Silent but trembling, the wife hid the extra plate. The husband rose calmly to lead the old man to a wall where a panel hissed open, and he stepped in and the panel